If Meta’s LLAMA series established the standard architecture for Dense models, then DeepSeek might be the founder of the standard MoE (Mixture of Experts) architecture. Of course, this does not mean DeepSeek invented MoE, nor that its MoE is unsurpassable. Rather, it means that several improvements proposed by DeepSeek for MoE are likely directions with significant performance gains, gradually becoming standard features of MoE. These include the Loss-Free load balancing scheme introduced in "MoE Tour: 3. A Different Way to Allocate", as well as the Shared Expert and Fine-Grained Expert strategies that will be introduced in this article.

Speaking of load balancing, it is undoubtedly a crucial goal for MoE. The 2nd to 4th posts in this series have essentially revolved around it. However, some readers have begun to realize that there is an unanswered fundamental question here: Putting aside efficiency requirements, is a uniform distribution necessarily the direction that yields the best performance? This article carries this question forward to understand Shared Expert and Fine-Grained Expert strategies.

Multiple Interpretations

We can understand Shared Expert from multiple perspectives. For example, from a residual perspective, it points out that the Shared Expert technique actually changes the task from learning each expert individually to learning the residual between it and the Shared Expert. This can reduce the difficulty of learning and provide better gradients. In DeepSeek’s words: by compressing common knowledge into these Shared Experts, redundancy among Routed Experts is reduced, improving parameter efficiency and ensuring each Routed Expert focuses on unique aspects.

If we compare Routed Experts to teachers of various subjects in a middle school, then the Shared Expert is like the "Head Teacher" (homeroom teacher). If a class only has subject teachers, each teacher will inevitably have to share some management work. Setting up the role of a Head Teacher concentrates these common management tasks on one person, allowing subject teachers to focus on teaching their specific disciplines, thereby improving teaching efficiency.

Of course, it can also be understood from a geometric perspective. The inevitable commonality between experts geometrically means that the angle between their vectors is less than 90 degrees. This contradicts the "pairwise orthogonality" assumption of expert vectors used when we proposed the geometric meaning of MoE in "MoE Tour: 1. Starting from Geometric Meaning". Although it can be understood as an approximate solution when this assumption does not hold, it is naturally better if it does. We can understand the Shared Expert as the mean of these Routed Experts. By learning the residual after subtracting the mean, the orthogonality assumption becomes easier to satisfy.

Scaling Factor

We can write Equation [eq:share-1] more generally as: \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{y} = \sum_{i=1}^s \boldsymbol{e}_i + \lambda\sum_{i\in \mathop{\text{argtop}}_{k-s} \boldsymbol{\rho}_{[s:]}} \rho_{i+s} \boldsymbol{e}_{i+s} \end{equation}

Since Routed Experts have weights \rho_{i+s} while Shared Experts do not, and the number of Routed Experts is usually much larger than the number of Shared Experts (i.e., n - s \gg s), their proportions might become unbalanced. To prevent one from being overshadowed by the other, setting a reasonable \lambda is particularly important. Regarding this, we proposed in "Muon is Scalable for LLM Training" that an appropriate \lambda should make the norms of both parts nearly identical during the initialization phase.

Specifically, we assume each expert has the same norm during initialization (without loss of generality, we can set it to 1) and satisfies pairwise orthogonality. We then assume the Router’s logits follow a standard normal distribution (zero mean, unit variance; other variances can be considered if necessary). In this case, the total norm of the s Shared Experts is \sqrt{s}, while the total norm of the Routed Experts is: \begin{equation} \lambda\sqrt{\sum_{i\in \mathop{\text{argtop}}_{k-s} \boldsymbol{\rho}_{[s:]}} \rho_{i+s}^2} \end{equation} By setting this equal to \sqrt{s}, we can estimate \lambda. Due to choices like activation functions and whether to re-normalize, the Routers of different MoEs may vary significantly. Therefore, instead of seeking an analytical solution, we use numerical simulation:

import numpy as np

def sigmoid(x):

return 1 / (1 + np.exp(-x))

def softmax(x):

return (p := np.exp(x)) / p.sum()

def scaling_factor(n, k, s, act='softmax', renorm=False):

factors = []

for _ in range(10000):

logits = np.random.randn(n - s)

p = np.sort(eval(act)(logits))[::-1][:k - s]

if renorm:

p /= p.sum()

factors.append(s**0.5 / (p**2).sum()**0.5)

return np.mean(factors)

# DeepSeek-V2 simulation

print(scaling_factor(162, 8, 2, 'softmax', False))

# DeepSeek-V3 simulation

print(scaling_factor(257, 9, 1, 'sigmoid', True))Coincidentally, the simulation results of this script align very well with the settings of DeepSeek-V2 and DeepSeek-V3. DeepSeek-V2 has n=162, k=8, s=2, uses Softmax activation without renormalization; the script’s result is approximately 16, and DeepSeek-V2’s \lambda is exactly 16 [Source]. DeepSeek-V3 has n=257, k=9, s=1, uses Sigmoid activation with renormalization; the script’s result is about 2.83, and DeepSeek-V3’s \lambda is 2.5 [Source].

Non-uniformity

Returning to the question at the beginning: Is balance necessarily the direction for best performance? It seems Shared Expert provides a reference answer: not necessarily. Shared Expert can be understood as certain experts always being activated, which leads to a non-uniform distribution of experts overall: \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{F} = \frac{1}{s+1}\bigg[\underbrace{1,\cdots,1}_{s \text{ experts}}, \underbrace{\frac{1}{n-s},\cdots,\frac{1}{n-s}}_{n-s \text{ experts}}\bigg] \end{equation}

In fact, non-uniform distributions are ubiquitous in the real world, so it should be easy to accept that a uniform distribution is not the optimal direction. Using the middle school teacher analogy again, the number of teachers for different subjects in the same school is actually non-uniform. Usually, Chinese, Math, and English have the most teachers, followed by Physics, Chemistry, and Biology, while PE and Art have fewer (and they often "get sick"). For more examples of non-uniform distributions, you can search for Zipf’s Law.

In summary, the non-uniformity of the real world inevitably leads to the non-uniformity of natural language, which in turn leads to the non-optimality of uniform distributions. Of course, from the perspective of training models, a uniform distribution is easier to parallelize and scale. Therefore, separating a portion as Shared Experts while still hoping the remaining Routed Experts are uniform is a compromise that is friendly to both performance and efficiency, rather than directly forcing Routed Experts to align with a non-uniform distribution.

That was about training; what about inference? During the inference stage, the actual distribution of Routed Experts can be predicted in advance, and backpropagation does not need to be considered. Therefore, with careful optimization, it is theoretically possible to maintain efficiency. However, since current MoE inference infrastructure is designed for uniform distributions, and there are practical constraints like limited GPU memory, we still hope Routed Experts remain uniform to achieve better inference efficiency.

Fine-Grained Expert

In addition to Shared Expert, another improvement proposed by DeepSeekMoE is the Fine-Grained Expert. it suggests that while keeping the total number of parameters and activated parameters constant, the finer the granularity of the experts, the better the performance tends to be.

For example, if we originally had a "k out of n" Routed Expert setup, and we now halve the size of each expert and change it to "2k out of 2n", the total parameters and activated parameters remain the same, but the latter often performs better. The original paper states that this enriches the diversity of expert combinations, i.e., \begin{equation} \binom{n}{k} \ll \binom{2n}{2k} \ll \binom{4n}{4k} \ll \cdots \end{equation}

Of course, we can have other interpretations. For instance, by further dividing experts into smaller units, each expert can focus on a narrower knowledge domain, achieving finer knowledge decomposition. However, it should be noted that Fine-Grained Expert is not cost-free. As n increases, the load among experts often becomes more unbalanced, and the communication and coordination costs between experts also increase. Therefore, n cannot increase indefinitely; there is a "sweet spot" where both performance and efficiency are favorable.

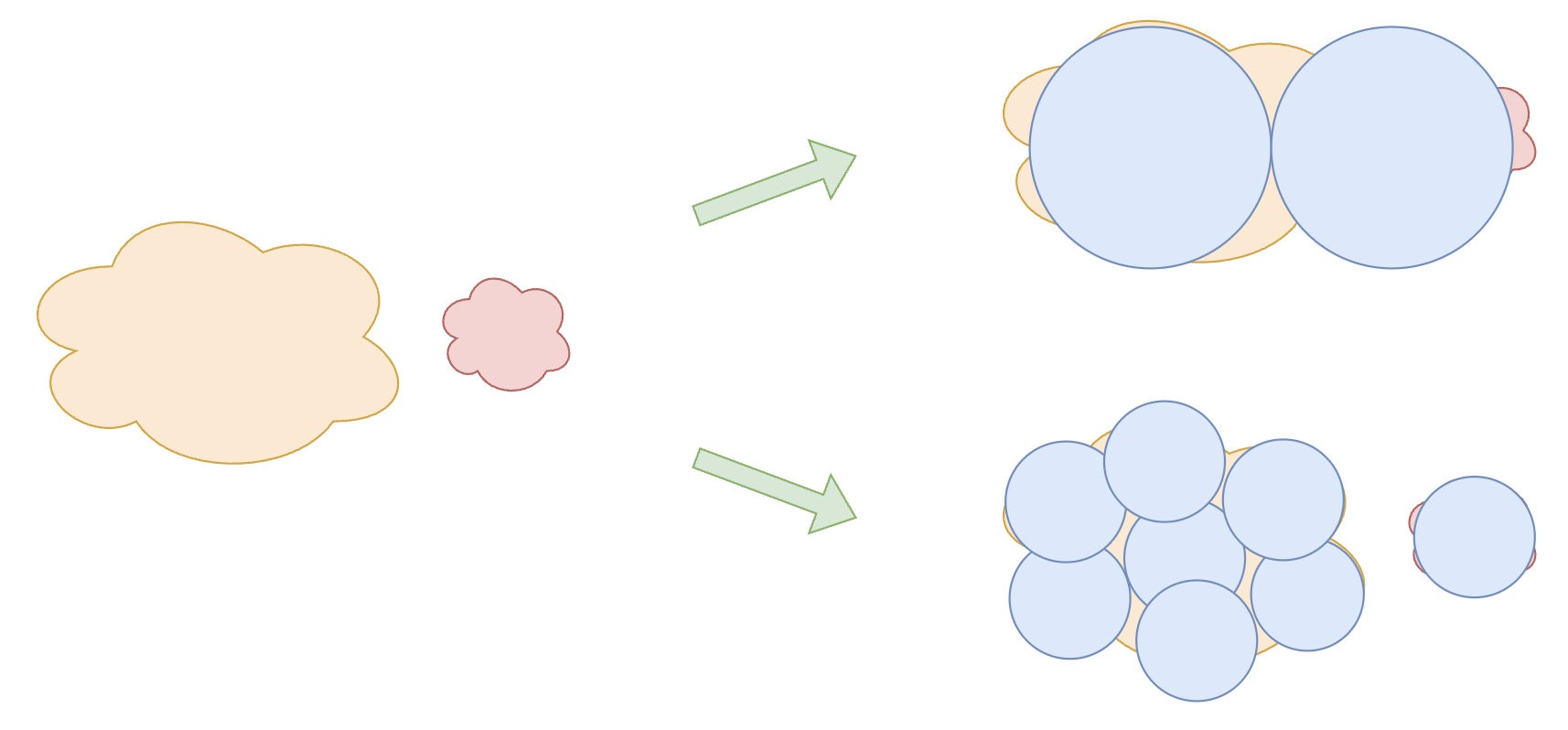

Regarding the effectiveness of Fine-Grained Expert, I propose another explanation that is less obvious but related to the theme of this article: a larger number of finer-grained experts can better simulate the non-uniformity of the real world. As shown in the figure below, suppose knowledge can be divided into two categories, one large and one small, and each expert is represented by a circle. If we use 2 large circles to cover them, there will be some omissions and waste. If we instead use 8 small circles with the same total area, we can cover the areas more precisely, thus achieving better results.

Summary

This article introduced the Shared Expert and Fine-Grained Expert strategies in MoE and pointed out that they both, to some extent, reflect the non-optimality of load balancing.

Reprinting please include the original address of this article: https://kexue.fm/archives/10945

For more detailed reprinting matters, please refer to: "Scientific Space FAQ"