In the problem of matrix compression, we generally have two strategies to choose from: low-rank approximation and sparsification. Low-rank approximation reduces matrix size by finding a low-rank representation, while sparsification reduces the complexity of the matrix by decreasing the number of non-zero elements. If Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is the go-to method for low-rank matrix approximation, what is the corresponding algorithm for finding a sparse approximation of a matrix?

Next, we will study the paper "Monarch: Expressive Structured Matrices for Efficient and Accurate Training", which provides an answer to the above question: the "Monarch matrix." This is a family of matrices that can be decomposed into the product of several permutation matrices and sparse matrices. They are both computationally efficient and highly expressive. The paper also discusses how to find the Monarch approximation of a general matrix and how to use Monarch matrices to parameterize Large Language Models (LLMs) to improve their speed.

It is worth noting that the author of this paper is Tri Dao, the creator of the famous Flash Attention. His work is almost entirely dedicated to improving the performance of LLMs. Monarch is also one of the few papers highlighted on his homepage, which alone makes it well worth studying.

SVD Review

First, let’s briefly review SVD (Singular Value Decomposition). For an n \times m matrix A, SVD decomposes it as: \begin{equation} A = U\Sigma V \end{equation} where U and V are orthogonal matrices of shapes n \times n and m \times m respectively, and \Sigma is an n \times m diagonal matrix with non-negative diagonal elements arranged in descending order. When we retain only the first r diagonal elements of \Sigma, we obtain an approximate decomposition of A with a rank no greater than r: \begin{equation} A \approx U_{[:,:r]}\Sigma_{[:r,:r]} V_{[:r,:]} \end{equation} Here, the subscripts follow Python-style slicing, so U_{[:,:r]} has shape n \times r, \Sigma_{[:r,:r]} has shape r \times r, and V_{[:r,:]} has shape r \times m, meaning the rank of U_{[:,:r]}\Sigma_{[:r,:r]} V_{[:r,:]} is at most r.

Specifically, the low-rank approximation obtained by SVD is the exact solution to the following optimization problem: \begin{equation} U_{[:,:r]}\Sigma_{[:r,:r]} V_{[:r,:]} = \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{\text{rank}(B)\leq r} \Vert A - B\Vert_F^2 \end{equation} where \Vert\cdot\Vert_F^2 is the square of the Frobenius norm, i.e., the sum of the squares of all elements in the matrix. In other words, under the Frobenius norm, the optimal rank-r approximation of matrix A is U_{[:,:r]}\Sigma_{[:r,:r]} V_{[:r,:]}. This conclusion is known as the "Eckart-Young-Mirsky theorem." This is why we said at the beginning that "SVD is aimed at low-rank approximation."

There is much more to discuss regarding SVD—enough to fill a book—but we won’t go deeper here. Finally, the computational complexity of SVD is \mathcal{O}(nm \cdot \min(m,n)), as we must perform an eigenvalue decomposition on either A^{\top}A or AA^{\top}. If we are certain that we are performing SVD to find a rank-r approximation, the complexity can be reduced, which is known as Truncated SVD.

Monarch Matrices

Low-rank decomposition is widely used, but it does not always meet our needs. For example, the low-rank approximation of an invertible square matrix is necessarily non-invertible, meaning low-rank approximation is unsuitable for scenarios requiring matrix inversion. In such cases, another option is sparse approximation. Sparse matrices can usually ensure that the rank does not degrade.

Note that sparsity and low-rankness are not necessarily related. For instance, the identity matrix is very sparse but invertible (full rank). Finding a sparse approximation of a matrix is not difficult; for example, setting all elements to zero except for the k elements with the largest absolute values is a very simple sparse approximation. However, the problem is that such an approach is usually not practical. The difficulty lies in finding a practical sparse approximation. "Practical" means maintaining sufficient expressiveness or approximation accuracy while achieving a certain degree of sparsity, and ensuring this sparsity has an appropriate structure that helps speed up matrix operations (such as multiplication and inversion).

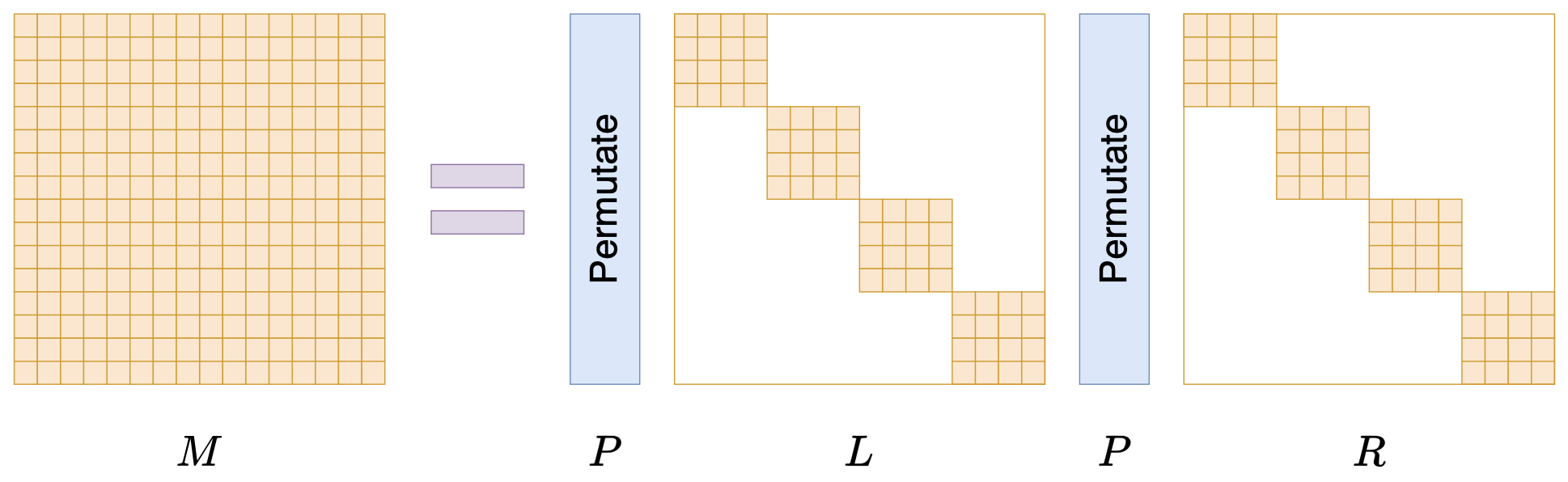

Monarch matrices were created for this purpose. Assuming n = m^2 is a perfect square, the Monarch matrix is a subset of all n \times n matrices, denoted as \mathcal{M}^{(n)}. It is defined as the set of matrices of the following form: \begin{equation} M = PLPR \end{equation} where P is an n \times n permutation matrix (an orthogonal matrix), and L, R are block-diagonal matrices. Let’s introduce them one by one.

Permutation Matrix

The permutation matrix P achieves the effect of permuting the vector [x_1, x_2, \cdots, x_n] into a new vector: \begin{equation} [x_1, x_{1+m}, \cdots , x_{1+(m-1)m}, x_2, x_{2+m}, \cdots , x_{2+(m-1)m}, \cdots , x_m, x_{2m}, \cdots , x_n] \end{equation} While this notation might seem confusing, the implementation in code is actually very simple:

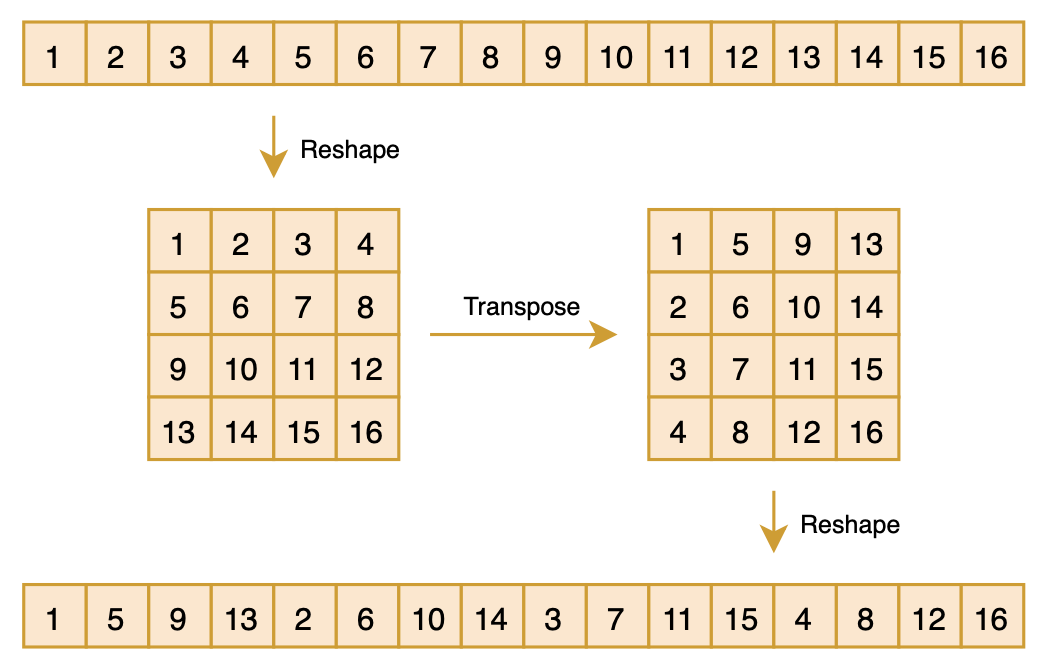

Px = x.reshape(m, m).transpose().reshape(n)As shown in the figure below:

Readers with a background in Computer Vision (CV) might find this operation familiar; it is essentially the "Shuffle" operation in ShuffleNet. This combination of reshaping, transposing, and reshaping back to the original size creates a "pseudo-shuffle" effect. It can also be viewed as an m-ary "bit-reversal permutation." Obviously, performing this operation twice restores the vector to its original state, so we have P^2 = I, which implies P^{-1} = P^{\top} = P.

Block Diagonal

After discussing P, let’s look at L and R. They are also n \times n matrices, but they are block-diagonal matrices with m \times m blocks. Each block is of size m \times m, as shown below:

When n is sufficiently large, the number of zeros in L and R dominates, so both L and R are sparse matrices. Thus, the Monarch matrix is a matrix decomposition form with sparse characteristics. Since P is fixed, the variable elements in PLPR come from the non-zero elements of L and R. Therefore, although M is an n \times n matrix, it actually has no more than 2m^3 = 2n^{1.5} free parameters. From the exponent 1.5, we can see the intent of Monarch matrices: they aim to reduce operations that originally required quadratic complexity to 1.5-power complexity through Monarch matrix approximation.

Efficiency Analysis

Can Monarch matrices achieve this goal? In other words, do they meet the "practical" standard mentioned earlier? We will discuss expressiveness later; let’s first look at computational efficiency.

For example, in "matrix-vector" multiplication, the standard complexity is \mathcal{O}(n^2). However, for a Monarch matrix, we have Mx = P(L(P(Rx))). Since multiplying by P involves only simple reshaping and transposing, it consumes almost no computation. The main computational load comes from multiplying L or R with a vector. Due to the block-diagonal nature of L and R, we can divide the vector into m groups, transforming the operation into m multiplications of m \times m matrices with m-dimensional vectors. The total complexity is 2m \times \mathcal{O}(m^2) = \mathcal{O}(2n^{1.5}), which is lower than \mathcal{O}(n^2).

Consider matrix inversion M^{-1}x. The standard complexity for inverting an n-th order matrix is \mathcal{O}(n^3). For a Monarch matrix, we have M^{-1}x = R^{-1}PL^{-1}Px. The main computational load comes from L^{-1}, R^{-1}, and the corresponding matrix-vector multiplications. Since L and R are block-diagonal, we only need to invert each block matrix on the diagonal. This involves inverting 2m matrices of size m \times m, with a complexity of 2m \times \mathcal{O}(m^3) = \mathcal{O}(2n^2), which is also lower than the standard \mathcal{O}(n^3). It is also possible to write out M^{-1} explicitly, but this requires using the identity in equation [eq:high-m-lr].

In conclusion, because multiplication by P is computationally negligible and L, R are block-diagonal, operations involving n-th order Monarch matrices can basically be transformed into 2m independent operations on m \times m matrices, thereby reducing the total computational complexity. Thus, Monarch matrices are certainly efficient, and since the non-zero elements of L and R already have a square structure, they are easy to implement and can fully utilize GPUs without unnecessary waste.

Monarch Factorization

After confirming the effectiveness of Monarch matrices, a key question for application is: given any n = m^2 order matrix A, how do we find its Monarch approximation? Similar to SVD, we define the following optimization problem: \begin{equation} \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{M\in\mathcal{M}^{(n)}} \Vert A - M\Vert_F^2 \end{equation} Fortunately, there is a solving algorithm for this problem with a complexity not exceeding \mathcal{O}(n^{2.5}), which is even more efficient than SVD’s \mathcal{O}(n^3).

High-Dimensional Arrays

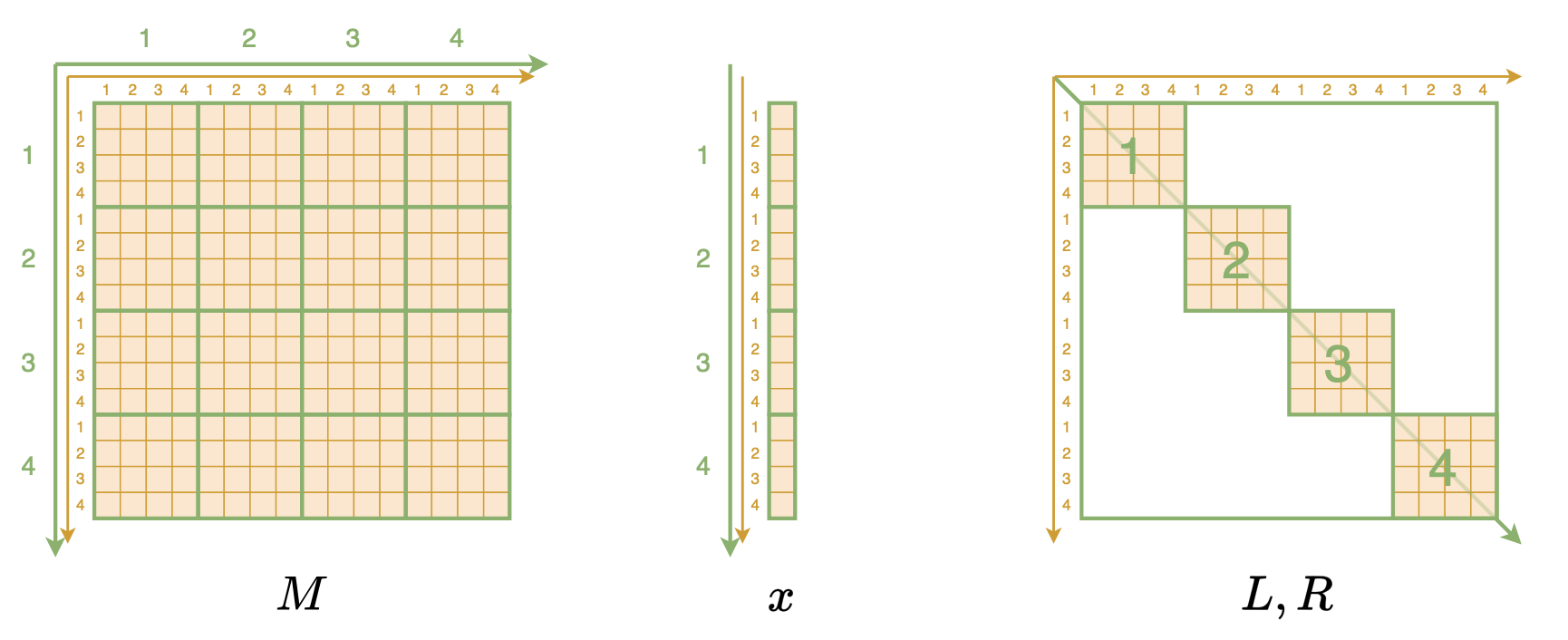

The key to understanding this algorithm is to transform Monarch-related matrices and vectors into higher-dimensional array forms. Specifically, the Monarch matrix M is originally a 2D array where each element M_{i,j} represents the element at the i-th row and j-th column. Now, based on the characteristics of block matrices, we represent it equivalently as a 4D array. Each element M_{i,j,k,l} represents the element in the i-th large row, j-th small row, k-th large column, and l-th small column, as shown below:

While it sounds complicated, the code is just one line:

M.reshape(m, m, m, m)Similarly, an n-dimensional (column)

vector x is converted into m \times m 2D data with

x.reshape(m, m). Naturally, L and R are

represented as m \times m \times m 3D

arrays, where L_{i,j,k} represents the

element in the i-th block, j-th small row, and k-th small column. This is already the most

efficient way to store L and R, but for unified processing, we can also

use the Kronecker delta

symbol to lift them to 4D, e.g., L_{i,j,k,l} = \delta_{i,k}L_{i,j,l} and R_{i,j,k,l} = \delta_{i,k}R_{i,j,l}.

A New Identity

Next, we will derive a new relationship between M and L, R. First, it can be proven that in the 2D representation, the multiplication of matrix P and vector x becomes simpler: the result is the transpose of x, i.e., (Px)_{i,j} = x_{j,i}. Therefore, we have (PR)_{i,j,k,l} = R_{j,i,k,l} = \delta_{j,k}R_{j,i,l}. Then, for the multiplication of two matrices in 4D representation, there are two summation indices: \begin{equation} (L P R)_{\alpha,\beta,k,l} = \sum_{i,j} L_{\alpha,\beta,i,j}(PR)_{i,j,k,l} = \sum_{i,j} \delta_{\alpha, i} L_{\alpha,\beta,j}\delta_{j,k}R_{j,i,l} = L_{\alpha,\beta,k}R_{k,\alpha,l} \end{equation} Finally, (P L P R)_{\alpha,\beta,k,l} = L_{\beta,\alpha,k}R_{k,\beta,l}. Replacing \alpha, \beta back with i, j, we get (P L P R)_{i,j,k,l} = L_{j,i,k}R_{k,j,l}. Since M = PLPR, we have: \begin{equation} M_{i,j,k,l} = L_{j,i,k}R_{k,j,l} \label{eq:high-m-lr} \end{equation} From this equation, we can see that when we fix a pair (j,k), the left side is a submatrix and the right side is the outer product of two vectors. This means that if we want to find the Monarch approximation for matrix A, we only need to convert A into a 4D array in the same way and fix a pair (j,k). The problem then becomes finding the "rank-1 approximation" of the corresponding submatrix! In other words, with this identity, finding the Monarch approximation of matrix A can be transformed into finding the "rank-1 approximation" of m^2 submatrices. This can be done using SVD, with each sub-problem having a complexity not exceeding \mathcal{O}(m^3), resulting in a total complexity not exceeding m^2 \times \mathcal{O}(m^3) = \mathcal{O}(n^{2.5}).

Reference Implementation

A simple reference implementation using Numpy is as follows:

import numpy as np

def monarch_factorize(A):

m = int(np.sqrt(A.shape[0]))

M = A.reshape(m, m, m, m).transpose(1, 2, 0, 3)

U, S, V = np.linalg.svd(M)

L = (U[:, :, :, 0] * S[:, :, :1]**0.5).transpose(0, 2, 1)

R = (V[:, :, 0] * S[..., :1]**0.5).transpose(1, 0, 2)

return L, R

def convert_3D_to_2D(LR, m, n):

X = np.zeros((m, m, m, m))

for i in range(m):

X[i, i] += LR[i]

return X.transpose(0, 2, 1, 3).reshape(n, n)

m = 8

n = m**2

A = np.where(np.random.rand(n, n) > 0.8, np.random.randn(n, n), 0)

L, R = monarch_factorize(A)

L_2d = convert_3D_to_2D(L, m, n)

R_2d = convert_3D_to_2D(R, m, n)

# P matrix implementation via reshape/transpose

def apply_P(X, m):

n = m*m

return X.reshape(m, m, n).transpose(1, 0, 2).reshape(n, n)

PL = apply_P(L_2d, m)

PR = apply_P(R_2d, m)

U, S, V = np.linalg.svd(A)

print('Monarch error:', np.square(A - PL.dot(PR)).mean())

print('Low-Rank error:', np.square(A - (U[:, :m] * S[:m]).dot(V[:m])).mean())I briefly compared the rank-m approximation obtained by SVD (where the parameter count is comparable to the Monarch approximation). I found that for completely dense matrices, the mean squared error of the rank-m approximation is often better than the Monarch approximation (though not by much). This is expected, as the Monarch approximation algorithm is essentially a customized version of SVD. However, if the matrix to be approximated is sparse, the Monarch approximation error is often better, and the sparser the matrix, the better the performance.

Monarch Generalization

So far, we have assumed that the matrices discussed are n-th order square matrices and that n = m^2 is a perfect square. While the square matrix condition might be acceptable, the n = m^2 condition is too restrictive. Therefore, it is necessary to generalize the concept of Monarch matrices at least to non-square n.

Non-Square Orders

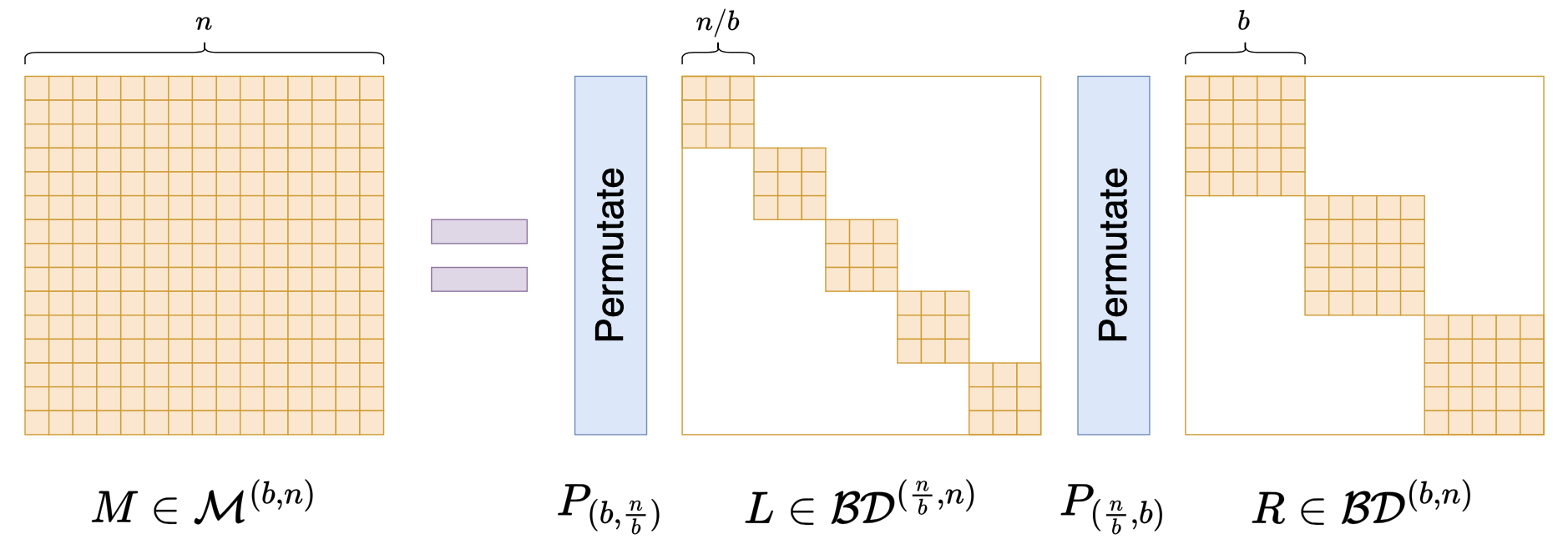

To this end, we first introduce some notation. Let b be a factor of n. \mathcal{BD}^{(b,n)} denotes the set of all

\frac{n}{b} \times \frac{n}{b}

block-diagonal matrices where each block is a b \times b submatrix. This is clearly a

generalization of the previous L and

R; using this notation, we can write

L, R \in \mathcal{BD}^{(\sqrt{n},n)}.

Furthermore, we need to generalize the permutation matrix P. Previously, we said P is implemented as

Px = x.reshape(m, m).transpose().reshape(n). Now we

generalize this to

Px = x.reshape(n // b, b).transpose().reshape(n), denoted

as P_{(\frac{n}{b},b)}.

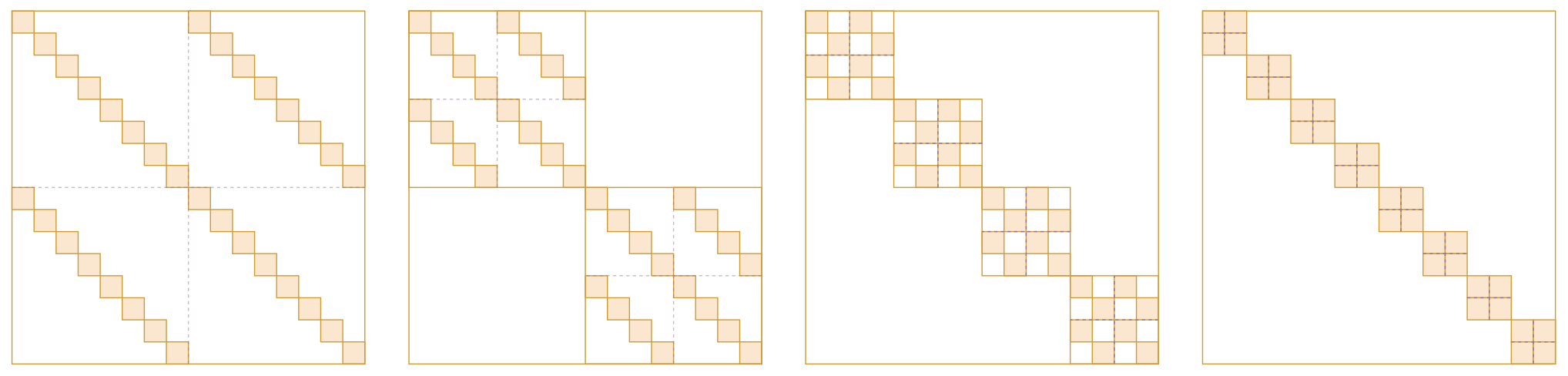

With these notations, we can define general Monarch matrices (from the original paper’s appendix): \begin{equation} \mathcal{M}^{(b,n)} = \Bigg\{M = P_{(b,\frac{n}{b})} L P_{(\frac{n}{b},b)} R\,\Bigg|\, L\in\mathcal{BD}^{(\frac{n}{b},n)}, R\in\mathcal{BD}^{(b,n)} \Bigg\} \end{equation} The schematic is as follows:

The Monarch matrix defined earlier can be simply denoted here as \mathcal{M}^{(n)} = \mathcal{M}^{(\sqrt{n},n)}. It is not difficult to calculate that L has at most \frac{n^2}{b} non-zero elements, and R has at most nb non-zero elements. The total is \frac{n^2}{b} + nb, which reaches its minimum at b = \sqrt{n}. Thus, b = \sqrt{n} is one of the sparsest examples.

Focusing on Form

Readers might wonder why we distinguish between L \in \mathcal{BD}^{(\frac{n}{b},n)} and R \in \mathcal{BD}^{(b,n)}. Why not use the same for both? In fact, this design is intended to keep the identity in equation [eq:high-m-lr] valid in high-dimensional representation, allowing for a similar decomposition algorithm and theoretically guaranteeing its expressiveness.

If we do not care about these theoretical details and only wish to construct a matrix parameterization with sparse characteristics, we can generalize Monarch matrices more flexibly, for example: \begin{equation} M = \left(\prod_{i=1}^k P_i B_i\right)P_0 \end{equation} where B_1, B_2, \cdots, B_k \in \mathcal{BD}^{(b,n)}, and P_0, P_1, \cdots, P_k are all permutation matrices. Multiplying by P_0 at the end is for symmetry and is not strictly necessary. If you find it necessary, you can even choose different b for each B_i, i.e., B_i \in \mathcal{BD}^{(b_i,n)}.

Furthermore, you can combine the form of low-rank decomposition to generalize to non-square block matrices, as shown below:

Based on this analogy, we can further extend the concept of Monarch matrices to non-square matrices. In short, if one only needs a sparse structured matrix similar to a Monarch matrix and does not care about theoretical details, the possibilities are limited only by our imagination.

Application Examples

Currently, the most significant feature of Monarch matrices is their friendliness to matrix multiplication. Therefore, their primary use is replacing the parameter matrices of fully connected layers to improve efficiency, which is the main content of the experimental section of the original paper.

We can categorize these into "pre-processing" and "post-processing": "Pre-processing" involves changing the parameter matrices of fully connected layers to Monarch matrices before training the model, so that both training and inference are accelerated, and the trained model is most compatible with Monarch matrices. "Post-processing" involves taking a pre-trained model and using Monarch decomposition to find a Monarch approximation for the parameter matrices of the fully connected layers, then replacing the original matrices and performing a simple fine-tuning if necessary to improve the fine-tuning or inference efficiency of the original model.

In addition to replacing fully connected layers, "Monarch Mixer: A Simple Sub-Quadratic GEMM-Based Architecture" discusses a more extreme approach—using it as a Token-Mixer module to directly replace the Attention layer. However, in my view, Monarch-Mixer is not particularly elegant because, like MLP-Mixer, it replaces the Attention matrix with a learnable matrix, which in this case is a Monarch matrix. This pattern learns static attention, and I have doubts about its generalizability.

Finally, for today’s LLMs, Monarch matrices can also be used to construct Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) schemes. We know that LoRA was designed based on low-rank decomposition. Since low-rank and sparsity are two parallel paths, shouldn’t Monarch matrices, as a representative of sparsity, also be used to construct a PEFT scheme? A quick search reveals that this has indeed been done in a paper titled "MoRe Fine-Tuning with 10x Fewer Parameters", which is quite recent and was part of an ICML 2024 Workshop.

The Monarch of Butterflies

Finally, let’s briefly discuss the fitting capability of Monarch matrices. "Monarch" refers to a ruler or sovereign, but it is taken from the term "Monarch Butterfly." It was named this way because it is positioned against the earlier "Butterfly matrix."

What is a Butterfly matrix? Explaining this is somewhat tedious. A Butterfly matrix is the product of a series of (\log_2 n) Butterfly factor matrices. A Butterfly factor matrix is a block-diagonal matrix whose diagonal matrices are called Butterfly factors (without the word "matrix"). A Butterfly factor is a 2 \times 2 block matrix where each block is a diagonal matrix (end of recursion). As shown below:

For the precise definition of a Butterfly matrix, please refer to the original paper; I won’t expand on it here. The name "Butterfly" comes from the author’s feeling that the shape of each Butterfly factor resembles a butterfly. Whether it actually looks like one is subjective, but the author thought so. Literally, a "Monarch Butterfly" is more advanced than a "Butterfly" (being a "Monarch"), implying that Monarch matrices are stronger than Butterfly matrices. Indeed, the appendix of the Monarch paper proves that regardless of the choice of b, \mathcal{M}^{(b,n)} can cover all n-th order Butterfly matrices, and when n > 512, \mathcal{M}^{(b,n)} is strictly larger than the set of all n-th order Butterfly matrices. In other words, whatever a Butterfly matrix can do, a Monarch matrix can also do, but the reverse is not necessarily true.

We can also intuitively perceive the expressiveness of Monarch matrices from the complexity of "matrix-vector" multiplication. We know that the standard complexity for multiplying an n \times n matrix by an n-dimensional vector is \mathcal{O}(n^2). However, for certain structured matrices, it can be lower: for example, the Fourier transform can achieve \mathcal{O}(n \log n), and the Butterfly matrix is also \mathcal{O}(n \log n). The Monarch matrix is \mathcal{O}(n^{1.5}), so the Monarch matrix "should" be no weaker than the Butterfly matrix. Of course, Butterfly matrices have their own advantages, such as their inverse and determinant being easier to calculate, which is more convenient for scenarios like Flow models that require inversion and determinants.

Summary

This article introduced the Monarch matrix, a family of matrices proposed by Tri Dao a couple of years ago that can be decomposed into the product of permutation matrices and sparse matrices. They are characterized by high computational efficiency (as we know, Tri Dao is synonymous with high performance) and can be used to speed up fully connected layers, construct parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods, and more.

When reposting, please include the original address: https://kexue.fm/archives/10249

For more details on reposting, please refer to: "Scientific Space FAQ"