As is well known, LoRA is a common parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) method, which we briefly introduced in "LoRA from a Gradient Perspective: Introduction, Analysis, Conjectures, and Generalization". LoRA utilizes low-rank decomposition to reduce the number of fine-tuning parameters and save VRAM. At the same time, the trained weights can be merged back into the original weights, requiring no changes to the inference architecture. This makes it a fine-tuning solution that is friendly to both training and inference. Furthermore, in "Can LoRA Gain a Bit More by Configuring Different Learning Rates?", we discussed the asymmetry of LoRA and pointed out that setting different learning rates for A and B can achieve better results, a conclusion known as "LoRA+".

To further improve performance, researchers have proposed many other LoRA variants, such as AdaLoRA, rsLoRA, DoRA, and PiSSA. While these modifications are reasonable, none felt particularly profound. However, the paper "LoRA-GA: Low-Rank Adaptation with Gradient Approximation" released a few days ago truly caught my eye. Just scanning the abstract gave me a sense that it would inevitably be effective, and after a careful reading, I feel it is the most brilliant LoRA improvement to date.

What makes it so brilliant? What is the actual value of LoRA-GA? Let’s explore it together.

Basics Revisited

First, let’s review LoRA. Suppose the pre-trained parameters are W_0 \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times m}. In full fine-tuning, the update amount is naturally also an n\times m matrix. LoRA constrains the update amount to be a low-rank matrix to reduce the number of parameters during training. Specifically, let W = W_0 + AB, where A \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times r}, B \in \mathbb{R}^{r\times m}, and r \ll \min(n, m). The original parameters are replaced by the new W, and W_0 is kept fixed while only A and B are trained, as shown below:

+ \times

To ensure that the initial state of LoRA is consistent with the pre-trained model, we usually initialize either A or B to zero, so that A_0 B_0 = 0, making the initial W equal to W_0. However, this is not strictly necessary. If both A and B are non-zero at initialization, we only need to set W as: \begin{equation} W = (W_0 - A_0 B_0) + AB \end{equation} In other words, by changing the fixed weight from W_0 to W_0 - A_0 B_0, we can still satisfy the condition that the initial W equals W_0.

It should be noted that LoRA is often a choice of necessity when VRAM is insufficient, as full fine-tuning generally outperforms LoRA. Therefore, if computational power is sufficient and the best performance is desired, full fine-tuning should be prioritized. This is also one of the assumptions of LoRA-GA, as its direction of improvement is to align with full fine-tuning. Another scenario for using LoRA is when there are numerous micro-customization needs; storing many fine-tuned results is much cheaper with LoRA.

Aligning with Full Fine-Tuning

LoRA-GA proposes a profound optimization point: through W = (W_0 - A_0 B_0) + AB, we can guarantee that the initial value of W equals W_0, meaning the initial state of LoRA is equivalent to full fine-tuning. Can we then adjust A_0 and B_0 so that LoRA and full fine-tuning remain as similar as possible in subsequent training? For example, at the simplest level, can we make W_1 after the first optimization step as equal as possible?

The more one reflects on this, the more one realizes how this optimization "hits the essence." Isn’t the goal of LoRA to "leverage small for large," hoping to approach the effect of full fine-tuning? If so, isn’t aligning the subsequent updates of full fine-tuning as closely as possible the most correct direction for improvement? From an approximation perspective, "initial W equals W_0" is a zero-order approximation of full fine-tuning. Keeping subsequent W_1, W_2, \dots close corresponds to higher-order approximations, which is a logical choice. This is why I felt "this is it" immediately after reading the abstract.

Specifically, assuming our optimizer is SGD, for full fine-tuning we have: \begin{equation} W_1 = W_0 - \eta \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial W_0} \end{equation} where \mathcal{L} is the loss function and \eta is the learning rate. For LoRA, we have: \begin{equation} \begin{gathered} A_1 = A_0 - \eta \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial A_0} = A_0 - \eta \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial W_0} B_0^{\top}, \quad B_1 = B_0 - \eta \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial B_0} = B_0 - \eta A_0^{\top}\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial W_0} \\[8pt] W_1 = W_0 - A_0 B_0 + A_1 B_1 \approx W_0 - \eta\left(A_0 A_0^{\top}\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial W_0} + \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial W_0}B_0^{\top} B_0\right) \end{gathered} \end{equation} The final approximation omits the second-order terms of \eta. Now both W_1 expressions have a similar form. To make them as close as possible, we can consider minimizing: \begin{equation} \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{A_0,B_0}\left\Vert A_0 A_0^{\top}\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial W_0} + \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial W_0}B_0^{\top} B_0 - \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial W_0}\right\Vert_F^2 \label{eq:loss-0} \end{equation} where \Vert\cdot\Vert_F^2 is the square of the Frobenius norm of the matrix, i.e., the sum of the squares of all elements in the matrix.

The Solution Process

For simplicity, let G_0 = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial W_0}. Then the objective [eq:loss-0] can be rewritten as: \begin{equation} \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{A_0,B_0}\left\Vert A_0 A_0^{\top}G_0 + G_0 B_0^{\top} B_0 - G_0\right\Vert_F^2 \label{eq:loss-1} \end{equation} Note that the ranks of A_0 A_0^{\top}G_0 and G_0 B_0^{\top} B_0 are at most r. Their sum has a rank of at most 2r. Assuming 2r < \min(n, m), the objective is equivalent to finding an optimal approximation of G_0 with a rank not exceeding 2r.

First, consider the case where G_0 is a non-negative diagonal matrix with diagonal elements sorted in descending order. This example is simple: its optimal rank-2r approximation is a new diagonal matrix that retains only the first 2r diagonal elements. This conclusion is known as the Eckart-Young-Mirsky Theorem. The A_0, B_0 that allow A_0 A_0^{\top}G_0 + G_0 B_0^{\top} B_0 to retain the first 2r diagonal elements of G_0 can be (using block matrices): \begin{equation} A_0 = (I_n)_{[:, :r]}, \quad B_0 = (I_m)_{[r:2r, :]} \end{equation} where I_n, I_m are identity matrices of order n and m, and {}_{[:, :r]} and {}_{[r:2r, :]} denote Python-style slicing, taking the first r columns and rows r+1 to 2r, respectively. Note that we say "can be," meaning the solution is not unique. Essentially, we need to pick out the first 2r diagonal elements of G_0, with A_0 A_0^{\top}G_0 and G_0 B_0^{\top} B_0 each picking half. The distribution doesn’t matter. The solution given above corresponds to A_0 A_0^{\top}G_0 picking the first r and G_0 B_0^{\top} B_0 picking the next r (from r+1 to 2r).

When G_0 is not a diagonal matrix, we perform SVD as G_0 = U\Sigma V, where U \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times n}, V \in \mathbb{R}^{m\times m} are orthogonal matrices, and \Sigma \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times m} is a diagonal matrix with non-negative diagonal elements sorted in descending order. Substituting into equation [eq:loss-1], we get: \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & \left\Vert A_0 A_0^{\top}G_0 + G_0 B_0^{\top} B_0 - G_0\right\Vert_F^2 \\ =& \left\Vert A_0 A_0^{\top}U\Sigma V + U\Sigma V B_0^{\top} B_0 - U\Sigma V\right\Vert_F^2 \\ =& \left\Vert U\left[(U^{\top}A_0) (U^{\top}A_0)^{\top}\Sigma + \Sigma (B_0 V^{\top})^{\top} (B_0 V^{\top}) - \Sigma \right]V\right\Vert_F^2 \\ =& \left\Vert (U^{\top}A_0) (U^{\top}A_0)^{\top}\Sigma + \Sigma (B_0 V^{\top})^{\top} (B_0 V^{\top}) - \Sigma\right\Vert_F^2 \end{aligned} \end{equation} The first two equalities are simple substitutions. The third equality holds because orthogonal transformations preserve the Frobenius norm. After this transformation, we see that the target of approximation has returned to the diagonal matrix \Sigma, and the variables have become U^{\top}A_0 and B_0 V^{\top}. Following the solution for the diagonal case, we obtain: \begin{equation} A_0 = U(I_n)_{[:, :r]} = U_{[:, :r]},\quad B_0 = (I_m)_{[r:2r, :]} V = V_{[r:2r, :]} \end{equation}

General Results

Now we have an initialization method for LoRA:

LoRA-GA selects a batch of samples, calculates the initial gradient G_0 = \nabla_{W_0}\mathcal{L}, performs SVD on the gradient as G_0 = U\Sigma V, takes the first r columns of U to initialize A, and takes rows r+1 to 2r of V to initialize B.

In this way, the W_1 obtained by LoRA + SGD is as close as possible to the W_1 of full fine-tuning. Furthermore, the direction of the gradient is more important than its magnitude, so the initialization result can be multiplied by a scale, and LoRA itself can also have a scale, i.e., W = (W_0 - \lambda A_0 B_0) + \lambda AB. These are common LoRA hyperparameters and will not be discussed further here. Incidentally, PiSSA is somewhat similar in form to LoRA-GA, but it performs SVD on W_0 to initialize A and B, which lacks the theoretical support of LoRA-GA and is a purely empirical choice.

Of course, some readers may notice that the current derivation is based on the assumption of an SGD optimizer. Should the conclusion change for the more commonly used Adam optimizer? Theoretically, yes. As discussed in "Can LoRA Gain a Bit More by Configuring Different Learning Rates?", for Adam, the first optimization result is W_1 = W_0 - \eta\, \text{sign}(G_0) instead of W_1 = W_0 - \eta G_0. Repeating the previous derivation, we get the optimization objective: \begin{equation} \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{A_0,B_0}\left\Vert A_0 \text{sign}(A_0^{\top}G_0) + \text{sign}(G_0 B_0^{\top}) B_0 - \text{sign}(G_0)\right\Vert_F^2 \label{eq:loss-adam} \end{equation} Due to the presence of the sign function, we cannot find an analytical solution, so the theoretical analysis for Adam stops here.

In this context, for the Adam optimizer, we have three choices:

Faith: Directly use the SGD result, believing it can also be effective in Adam;

Hard-core: Use an optimizer to directly minimize the objective [eq:loss-adam]. Since the objective is relatively simple, the computational cost is acceptable;

Speculative: Intuitively replace G_0 with \text{sign}(G_0) and then apply the SGD conclusion, which might better fit Adam.

It appears the original paper chose the first option, and the experimental results indeed support this choice.

Experimental Results

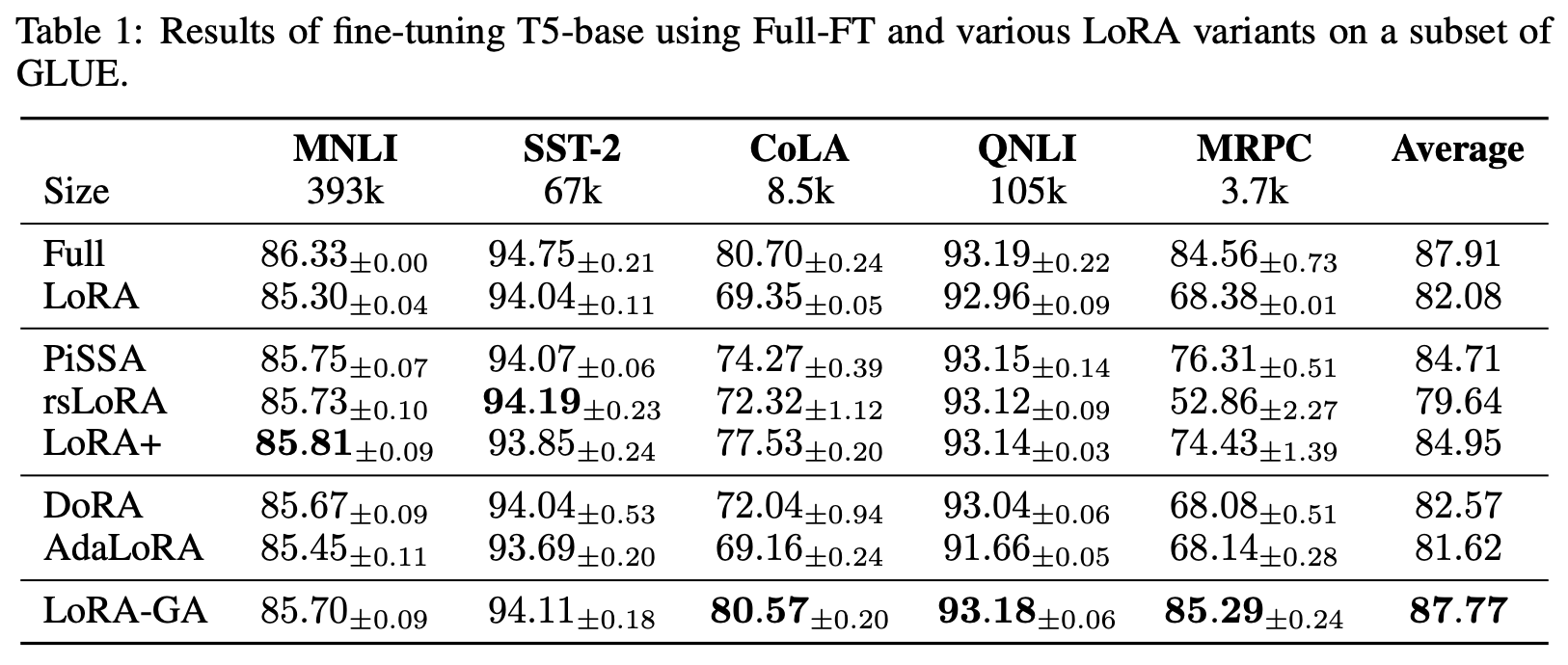

The experimental results in the paper are quite impressive, especially on GLUE, where it achieved performance closest to full fine-tuning:

On average, the smaller the amount of training data, the larger the relative improvement. This indicates that LoRA-GA’s strategy of aligning with full fine-tuning not only helps improve the final effect but also improves training efficiency, meaning it can achieve better results with fewer training steps.

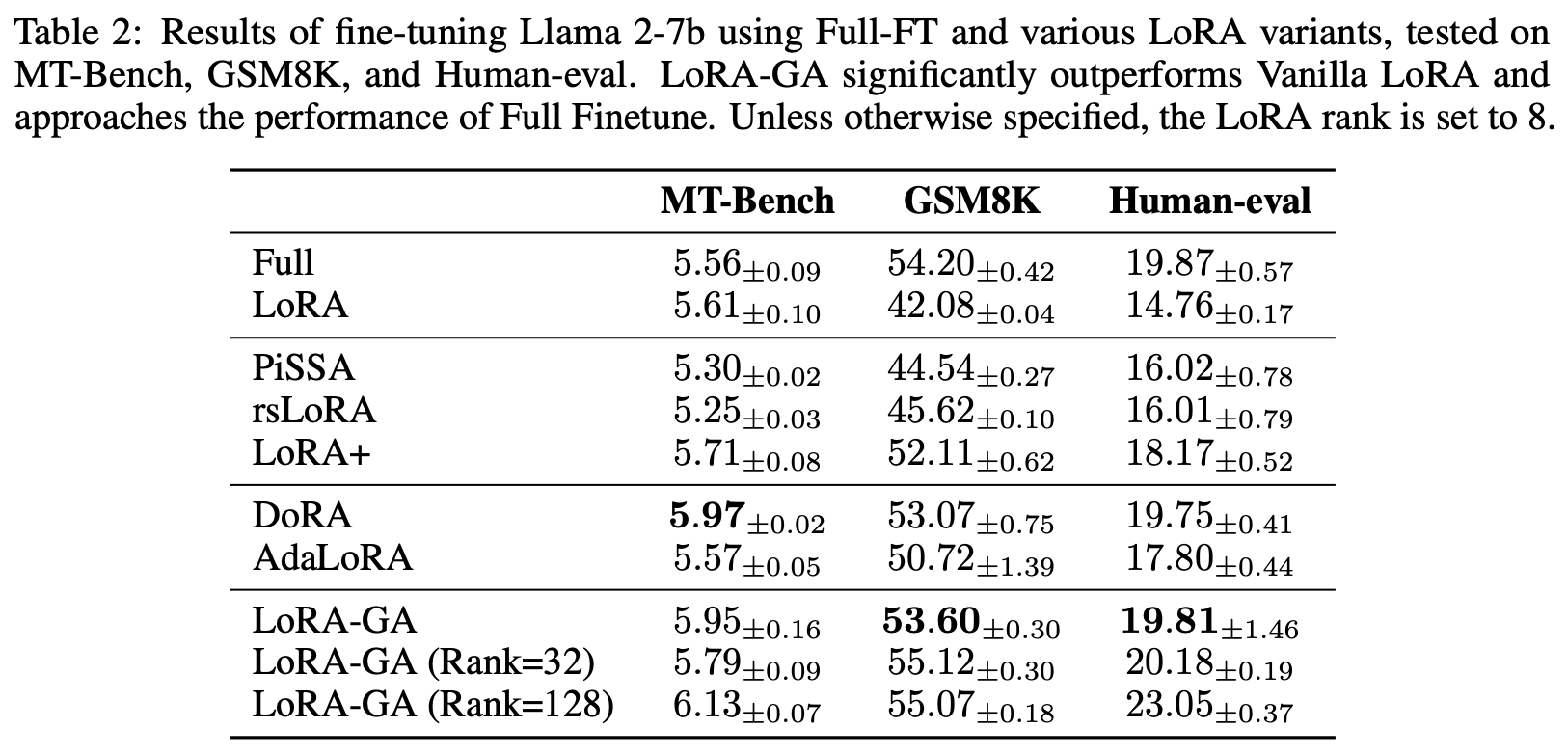

Its performance on LLAMA2-7b is also noteworthy:

Note that the main scenario for using LoRA is insufficient VRAM, but LoRA-GA’s initialization requires calculating the full gradient of all training parameters, which might be impossible due to VRAM constraints. To address this, the original paper suggests a trick: we can calculate the gradients for parameters one by one (serially) instead of simultaneously. This reduces the VRAM required for a single step. Although serial gradient calculation reduces efficiency, initialization is a one-time task, so being a bit slower is acceptable. The implementation details vary across frameworks and will not be discussed here.

Summary

This article introduced a new improvement to LoRA called LoRA-GA. Although various LoRA variants are not uncommon, LoRA-GA impressed me with its very intuitive theoretical guidance. The improvement logic gives a sense of "this is the right paper," and combined with solid experimental results, the whole process is smooth and aesthetically pleasing.

Original address: https://kexue.fm/archives/10226

For more details on reprinting, please refer to: "Scientific Space FAQ"