In the second article of this series, "Transformer Upgrade Road: 2. Rotary Position Encodings (RoPE) Drawing from Various Strengths", I proposed Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE)—a scheme that implements relative position encoding through an absolute position form. Initially, RoPE was designed for one-dimensional sequences such as text and audio (RoPE-1D). Later, in "Transformer Upgrade Road: 4. Rotary Position Encodings for 2D Positions", we extended it to two-dimensional sequences (RoPE-2D), which is suitable for Vision Transformers (ViT). However, whether it is RoPE-1D or RoPE-2D, their common characteristic is a single modality, i.e., pure text or pure image input scenarios. So, for multimodal scenarios like mixed image-text inputs, how should RoPE be adjusted?

I searched around and found very few works discussing this issue. The mainstream practice seems to be directly flattening all inputs and treating them as a one-dimensional input to apply RoPE-1D; consequently, even RoPE-2D is rarely seen. Setting aside whether this approach will become a performance bottleneck as image resolution increases, it ultimately feels insufficiently elegant. Therefore, in the following, we attempt to explore a natural combination of the two.

Rotational Position

The word "Rotary" in the name RoPE comes from the rotation matrix \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n=\begin{pmatrix}\cos n\theta & -\sin n\theta\\ \sin n\theta & \cos n\theta\end{pmatrix}, which satisfies: \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_m^{\top}\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n=\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} \end{equation} In this way, for the dot product of \boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{k} (assuming they are column vectors), we have: \begin{equation} \left(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_m\boldsymbol{q}\right)^{\top} \left(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n\boldsymbol{k}\right)= \boldsymbol{q}^{\top}\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_m^{\top}\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n \boldsymbol{k}=\boldsymbol{q}^{\top}\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m}\boldsymbol{k} \end{equation} In the leftmost expression, \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_m\boldsymbol{q} and \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n\boldsymbol{k} are performed independently, involving no interaction between m and n, so it is formally an absolute position. However, the equivalent form on the far right depends only on the relative position n-m. Thus, when combined with Dot-Product Attention, it essentially behaves as a relative position. This property also gives RoPE translation invariance: since (n+c) - (m+c) = n-m, if a constant is added to all absolute positions before applying RoPE, the result of the Attention theoretically remains unchanged (in practice, there may be minor errors due to computational precision).

The above is the form for \boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{k} \in \mathbb{R}^2. For \boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{k} \in \mathbb{R}^d (where d is even), we need a d \times d rotation matrix. For this, we introduce d/2 different \theta values and construct a block diagonal matrix: \begin{equation} \small{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n^{(d\times d)} = \begin{pmatrix} \cos n\theta_0 & -\sin n\theta_0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \sin n\theta_0 & \cos n\theta_0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \cos n\theta_1 & -\sin n\theta_1 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \sin n\theta_1 & \cos n\theta_1 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \cos n\theta_{d/2-1} & -\sin n\theta_{d/2-1} \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \sin n\theta_{d/2-1} & \cos n\theta_{d/2-1} \\ \end{pmatrix}} \end{equation} From an implementation perspective, this involves grouping \boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{k} into pairs, with each pair taking a different \theta for a 2D rotational transformation. These are existing RoPE details and will not be expanded further. In principle, we only need to find a solution for the lowest dimension, and then it can be extended to general dimensions via block diagonalization. Therefore, the following analysis only considers the minimum dimension.

Two-Dimensional Position

When we talk about the concept of "dimension," it can have multiple meanings. For example, when we just said \boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{k} \in \mathbb{R}^d, it means \boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{k} are d-dimensional vectors. However, the RoPE-1D and RoPE-2D focused on in this article do not refer to this dimension, but rather to the number of dimensions required to record a position.

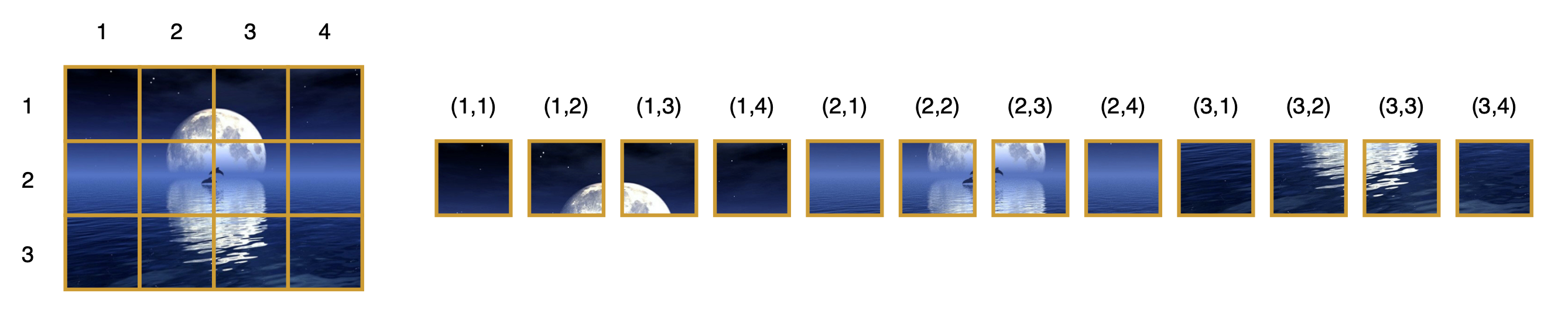

For instance, if we want the position of a token in text, we only need a scalar n to record that it is the n-th token. But for an image, even after patchification, it usually retains two directional dimensions: width and height. Thus, we need a pair of coordinates (x, y) to accurately encode the position of a patch:

The \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n introduced in the previous section only encodes a scalar n, so it is RoPE-1D. To handle image inputs more reasonably, we need to generalize it to the corresponding RoPE-2D: \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{x,y}=\left( \begin{array}{cc:cc} \cos x\theta & -\sin x\theta & 0 & 0 \\ \sin x\theta & \cos x\theta & 0 & 0 \\ \hdashline 0 & 0 & \cos y\theta & -\sin y\theta \\ 0 & 0 & \sin y\theta & \cos y\theta \\ \end{array}\right) = \begin{pmatrix}\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_x & 0 \\ 0 & \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_y\end{pmatrix} \end{equation} Obviously, this is just \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_x and \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_y combined in a block diagonal form, so it can naturally be extended to 3D or even higher dimensions. From an implementation standpoint, it is even simpler: it involves splitting \boldsymbol{q}, \boldsymbol{k} into two halves (three equal parts for 3D, four for 4D, and so on), where each half is a vector in \mathbb{R}^{d/2}. Then, one half undergoes RoPE-1D for x, and the other half undergoes RoPE-1D for y, before they are concatenated back together.

It should be noted that for considerations of symmetry and simplicity, the \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{x,y} constructed above uses the same \theta for both x and y, but in principle, this is not mandatory. In appropriate circumstances, we could configure slightly different \theta values for x and y respectively.

Forced Dimensionality Reduction

We now see that the position of text is a scalar n, while the position of an image is a vector (x, y). The two are inconsistent. Therefore, when processing mixed image-text inputs, some techniques are needed to reconcile this inconsistency.

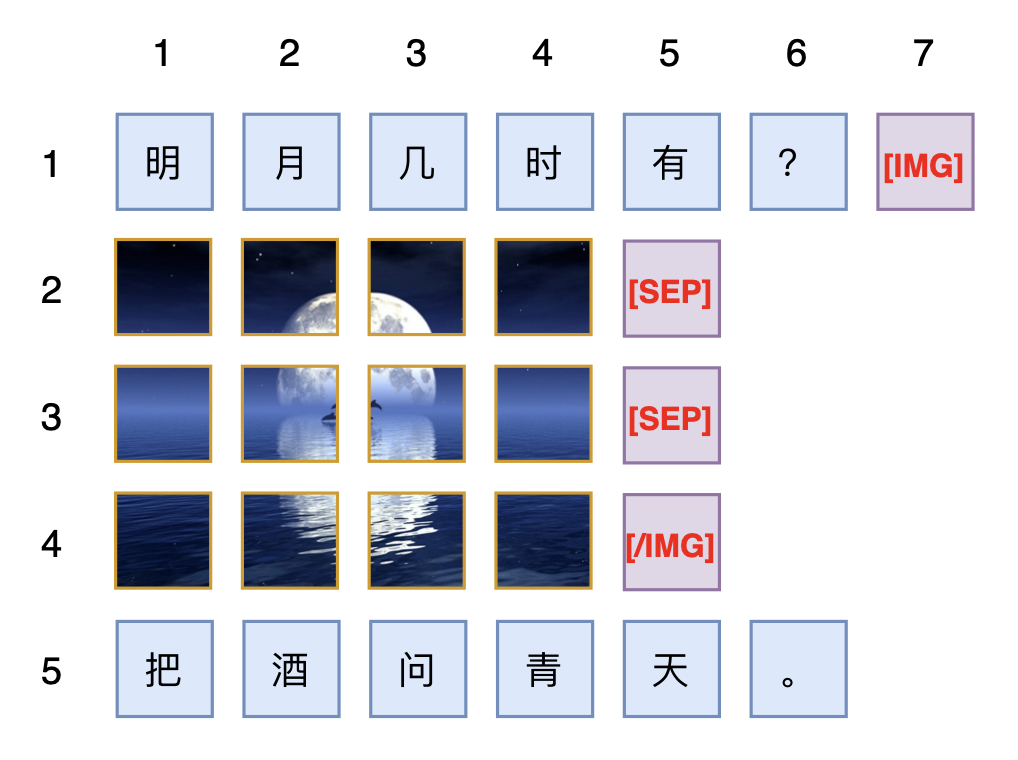

The most direct solution, as mentioned at the beginning of the article, is to directly flatten the image into a sequence of one-dimensional vectors and then treat it like ordinary text. Whatever position encoding is applied to text is applied to the image. This approach is naturally very general and is not limited to RoPE; it can be used with any absolute position encoding. I observe that some existing multimodal models, such as Fuyu-8b, Deepseek-VL, and Emu2, all do this. There might be differences in detail; for example, when encountering patches from different rows, one might consider adding a special token representing [SEP] as a separator:

This scheme also fits the current mainstream Decoder-Only architecture, because Decoder-Only implies that even without position encoding, it is not permutation-invariant. Therefore, we must manually specify what we consider the optimal input order. Since an input order must be specified, using 1D position encoding according to that specified order is a natural choice. Furthermore, in pure text scenarios, a model using this scheme is no different from a standard pure-text LLM, which allows us to continue training a pre-trained text LLM into a multimodal model.

However, from my perspective, the concept of position encoding itself should not be bound to the usage of Attention; it should be universally applicable to Decoders, Encoders, and any Attention Mask. On the other hand, maintaining the two-dimensionality of position is the only way to preserve our priors about adjacent positions to the greatest extent. For example, we believe that positions (x+1, y) and (x, y+1) should both have similar distances to (x, y). But if we flatten them (e.g., horizontal then vertical), (x, y) becomes xw + y, while (x+1, y) and (x, y+1) become xw + y + w and xw + y + 1 respectively. The distance of the former from xw + y depends on w, while the latter is a fixed 1. Of course, we could specify other ordering sequences, but no matter how the order is specified, it is impossible to fully accommodate the proximity of all neighboring positions. After all, with one less dimension, the expressible similarity is much reduced.

Unified Dimensionality Increase

From the perspective of vector spaces, a one-dimensional scalar can be viewed as a special two-dimensional vector. Therefore, compared to flattening into 1D, if we conversely unify the positions of all inputs into 2D, there is theoretically more room for operation.

To this end, we can consider a common typesetting method: using images as delimiters to segment text. Continuous text is treated as a single line, while an image is treated as multiple lines of text. Then the entire mixed image-text input is equivalent to a multi-line long document. Each text token or image patch has its own row number x and its order within the row y. This assigns a 2D position (x, y) to all input units (tokens or patches), allowing for a unified use of RoPE-2D (other 2D position encodings could also work) to encode positions while maintaining the original 2D nature of image positions.

Clearly, the main advantage of this scheme is that it is very intuitive, directly corresponding to actual visual layouts, making it easy to understand and extend. However, it also has a very obvious disadvantage: for pure text input, it cannot degenerate into RoPE-1D; instead, it becomes RoPE-2D where x is always 1. Thus, the feasibility of training a multimodal LLM starting from a pre-trained text LLM becomes questionable. Furthermore, if images are used as split points, when there are many images, the text might be segmented too "fragmentedly." Specific manifestations include large fluctuations in the length of each text segment and continuous text being forced into new lines, all of which could become bottlenecks limiting performance.

Combining the Two

If we want to preserve the position information of image patches losslessly, then unifying to 2D and using RoPE-2D (or other 2D position encodings) seems to be the inevitable choice. Therefore, the scheme in the previous section is already moving in the right direction. What we need to further consider is how to make it degenerate into RoPE-1D for pure text input to be compatible with existing text LLMs.

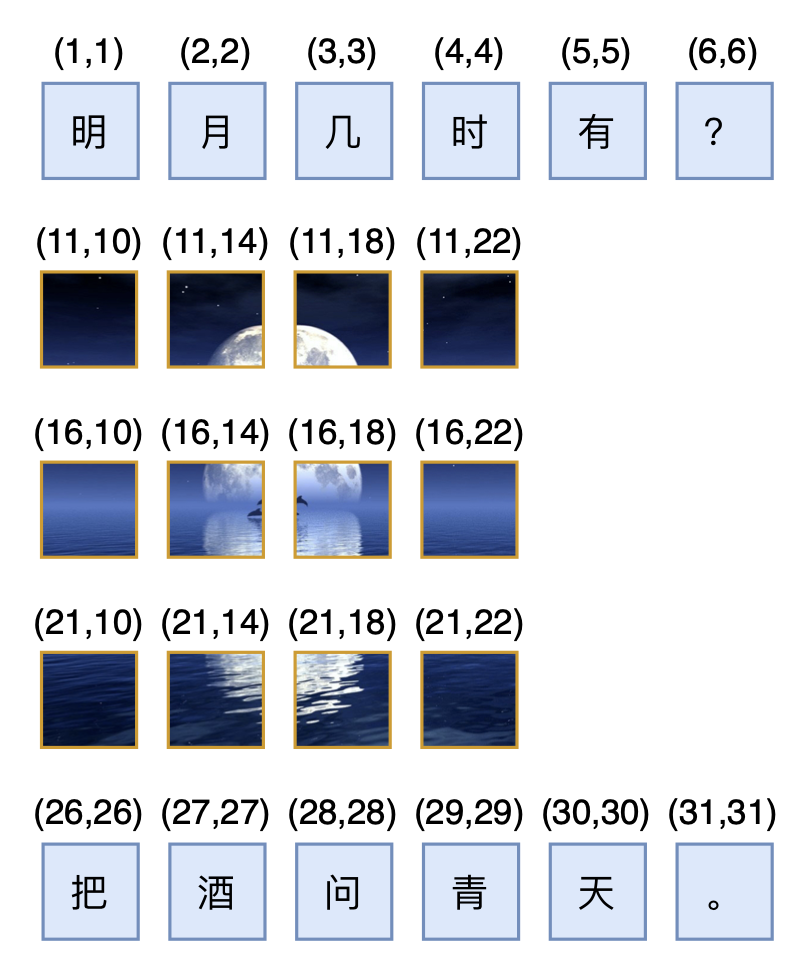

First, as mentioned earlier, \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{x,y} is a block diagonal combination of \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_x and \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_y. Thus, \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n,n} is a block diagonal combination of two \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n matrices. Since the RoPE-1D matrix \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n^{(d\times d)} is also a block diagonal combination of multiple \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n matrices with different \theta values, it follows that as long as we select different \theta values from \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n^{(d\times d)} for x and y, then \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n,n} can be seen as a part of RoPE-1D (i.e., \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n^{(d\times d)}). From this, it appears that for RoPE-2D to degenerate into RoPE-1D, the position of text should take the form (n, n), rather than specifying a row number in other ways as in the previous section.

Then, inside the image, we use standard RoPE-2D. For a single image with w \times h patches, its 2D position coordinates after flattening are:

| x | 1 | 1 | \cdots | 1 | 2 | 2 | \cdots | 2 | \quad \cdots \quad | h | h | \cdots | h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| y | 1 | 2 | \cdots | w | 1 | 2 | \cdots | w | \quad \cdots \quad | 1 | 2 | \cdots | w |

If this image is placed after a sentence of length L, the position encoding of the last token of this sentence is (L, L). Thus, the position encoding of the image following the sentence should look like:

| x | L+1 | L+1 | \cdots | L+1 | \quad \cdots \quad | L+h | L+h | \cdots | L+h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| y | L+1 | L+2 | \cdots | L+w | \quad \cdots \quad | L+1 | L+2 | \cdots | L+w |

But this is not perfect. Because the position of the last token of the sentence is (L, L) and the position of the first patch of the image is (L+1, L+1), they differ by (1, 1). Suppose another sentence follows this image; let the position of the first token of that sentence be (K, K). The position of the last patch of the image is (L+h, L+w). When w \neq h, no matter how we set K, it is impossible to make the difference between (K, K) and (L+h, L+w) equal to (1, 1). That is, the image exhibits asymmetry with respect to the surrounding sentences, which is not elegant enough.

To improve this, we can multiply the x, y of the image by positive numbers s, t respectively:

| x | s | s | \cdots | s | 2s | 2s | \cdots | 2s | \quad \cdots \quad | hs | hs | \cdots | hs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| y | t | 2t | \cdots | wt | t | 2t | \cdots | wt | \quad \cdots \quad | t | 2t | \cdots | wt |

As long as s, t \neq 0, this scaling is lossless for position information, so such an operation is permitted. After introducing the scales, assuming the position of the last token of the sentence is still (L, L), the position of the image is the above sequence with L added to each. At this point, the difference between the "position of the last token of the sentence" and the "position of the first patch of the image" is (s, t). If we want the difference between the "position of the first token of the sentence following the image" and the "position of the last patch of the image" to also be (s, t), then we should have: \begin{equation} \begin{pmatrix}L + hs \\ L + wt \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix}s \\ t \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}K \\ K \end{pmatrix}\quad \Rightarrow \quad (h+1)s = (w+1)t \end{equation} Considering the arbitrariness of h, w, and wanting to ensure that position IDs are integers, the simplest solution is naturally s=w+1, t=h+1. The position of the first token of the new sentence will be K=L+(w+1)(h+1). A specific example is shown in the figure below:

Extended Thoughts

The position of the last token of the sentence on the left is L, and the position of the first token of the sentence on the right is K=L+(w+1)(h+1). If the middle part were also a sentence, it would imply that the sentence has (w+1)(h+1)-1 tokens. This is equivalent to saying that if an image of w \times h is sandwiched between two sentences, it is equivalent to a sentence of (w+1)(h+1)-1 tokens in terms of the relative positions of the two sentences. This number looks a bit unnatural, as wh seems like the perfect answer, but unfortunately, this is the simplest solution to ensure all position IDs are integers. If non-integer position IDs are allowed, one could stipulate that a w \times h image is equivalent to wh tokens, which in turn implies: \begin{equation} s = \frac{wh + 1}{h+1}, \quad t = \frac{wh + 1}{w+1} \end{equation}

Some readers might ask: what if two images of different sizes are adjacent? Is there no such symmetrical scheme? This is actually not difficult; as long as we add special tokens like [IMG] and [/IMG] before and after each image, and treat these special tokens as ordinary text tokens for position encoding, we directly avoid the situation where two images are directly adjacent (because by convention, the patches of the same image are necessarily sandwiched between [IMG] and [/IMG], and these two tokens are treated as text, meaning every image is necessarily sandwiched between two pieces of text). Furthermore, [SEP] was not mentioned in the above introduction; if needed, it can be introduced. In fact, [SEP] is only necessary when generating images in a patch-by-patch autoregressive manner. If the image is purely an input, or if image generation is done using diffusion models, then [SEP] is redundant.

At this point, our derivation for extending RoPE to mixed image-text inputs is complete. If a name is needed, the final scheme can be called "RoPE-Tie (RoPE for Text-image)". It must be said that the final RoPE-Tie is not particularly beautiful, to the point of giving a sense of "over-engineering." In terms of effect, compared to directly flattening into 1D and using RoPE-1D, switching to RoPE-Tie might not necessarily bring any improvement; it is more a product of my obsessive-compulsive disorder. Therefore, for multimodal models that have already scaled to a certain size, there is no need to make any changes. But if you haven’t started yet or are just starting, you might as well try RoPE-Tie.

Summary

This article discussed how to combine RoPE-1D and RoPE-2D to better handle mixed image-text input formats. The main idea is to support 2D position indices for images through RoPE-2D and, through appropriate constraints, allow it to degenerate into conventional RoPE-1D in pure text scenarios.

Original Address: https://kexue.fm/archives/10040

For more details on reprinting, please refer to: "Scientific Space FAQ"