In this article, I will share some of my “closed-door” thoughts—or rather, some conjectures—regarding multimodal model architectures.

Recently, Google’s Gemini 1.5 and OpenAI’s Sora have once again ignited enthusiasm for multimodality. The brief technical reports have also sparked intense speculation about the model architectures behind them. However, this article is not being published just to join the hype. In fact, some of these reflections have been brewing for a long time, and I have only recently managed to organize them. I wanted to write them down to exchange ideas with everyone, and it just so happened to coincide with these releases.

A disclaimer: the phrase “building a car behind closed doors” is not false modesty. My practice in large models is “unremarkable,” and my multimodal practice is almost a “blank slate.” This article is indeed just a “subjective conjecture” based on my past experience in text and image generation.

Problem Background

First, let’s simplify the problem. The multimodality discussed in this article mainly refers to the dual-modality of image and text, where both input and output can be either. Many readers might initially feel: Isn’t multimodal modeling just about burning money on GPUs, using Transformer for everything, and eventually achieving “miracles through brute force”?

It is not that simple. Let’s look at text generation first. In fact, text generation has followed only one mainstream path from the beginning: language modeling, which models the conditional probability p(x_t|x_1,\cdots,x_{t-1}). Whether it was the original n-gram models or the later Seq2Seq and GPT, they are all approximations of this conditional probability. In other words, people have always been clear about “which direction to go to achieve text generation”; only the underlying models have changed, such as LSTM, CNN, Attention, and even the recently revived linear RNNs. Therefore, text generation can indeed go “all in” on Transformers to create miracles because the direction is standard and clear.

However, for image generation, there is no such “standard direction.” Among the image generation models discussed on this site, there are VAE, GAN, Flow, Diffusion, as well as niche methods like EBM and PixelRNN/PixelCNN. The distinction between these methods is not just because they use RNN, CNN, or Attention, leading to different results, but because their underlying modeling theories are fundamentally different. The fundamental reason for the diversity of image generation methods is the difficulty of probabilistic modeling for continuous variables.

For a sentence (x_1,x_2,\cdots,x_l) of length l, each x_t comes from a finite vocabulary. Thus, p(x_t|x_1,\cdots,x_{t-1}) is essentially a classification task. Combined with the “universal approximation capability of neural networks + Softmax,” any classification task can theoretically be modeled precisely. This is the theoretical guarantee behind text generation. However, we usually treat images as continuous vectors, so for an image, x_t is a real number. Even if we apply the same conditional decomposition, how do we model p(x_t|x_1,\cdots,x_{t-1})? Note that here p(x_t|x_1,\cdots,x_{t-1}) is a probability density, and a necessary condition for a probability density is that it is non-negative and integrates to 1: \begin{equation} \int p(x_t|x_1,\cdots,x_{t-1}) dx_t = 1 \end{equation} Besides the normal distribution, how many functions can we write whose integral is always 1? And the functions we can write, like the normal distribution, are not sufficient to fit arbitrarily complex distributions. Simply put, neural networks are universal function approximators, but they are not universal probability density approximators. This is the inherent difficulty of generative modeling for continuous variables. Various image generation schemes are essentially different ways to bypass direct modeling of probability density (except for Flow). Discrete variables do not face this difficulty because the constraint for discrete probability is that the sum is 1, which can be achieved via Softmax.

The Discrete Path

At this point, some readers might think: Can we discretize images and then apply the text generation framework? Yes, this is currently one of the mainstream ideas (and possibly the only one).

In fact, images are inherently discrete. An RGB image of size n\times n is actually 3n^2 integers from 0 to 255. That is, it is

equivalent to a sentence with a length of 3n^2 and a vocab_size of 256.

Broadly speaking, computers are inherently discrete; everything they

represent is discrete, whether it is text, images, audio, or video. So,

theoretically, there is no problem with using their original discrete

representations in a text generation framework. Early works like PixelRNN and PixelCNN performed

autoregressive generation directly in the pixel space. The OpenAI Sparse

Transformer, which we introduced in “Born for Efficiency: From

Standard Attention to Sparse Attention”, also had pixel-level image

autoregression as one of its primary experiments.

However, the biggest problem with operating directly in pixel space is that the sequence is too long and generation is too slow. In most applications, image resolution must be at least 256 to be practical. Even if n=256, 3n^2 \approx 200,000. This means that to generate a 256 \times 256 image, we need 200,000 steps of autoregressive decoding! Although Long Context technology has made significant progress recently, this cost remains very high, and the generation time is difficult to accept.

To address this, an easy idea is “compress first, generate later.” That is, use another model to compress the sequence length, perform generation in the compressed space, and then restore it to an image. Compression naturally relies on AE (AutoEncoder), but since we want to use the text generation modeling approach, we must ensure discreteness after compression. This requires VQ-VAE or the later VQ-GAN, where VQ can also be replaced by the recent FSQ. Similar to a text Tokenizer, VQ-VAE/GAN acts as an “Image Tokenizer.” It maintains the discreteness of the encoding results but significantly reduces the sequence length (e.g., if the resolution is reduced to 1/4, then 3n^2 \to (n/4)^2, a 48-fold reduction), and it can be restored to the original image via a corresponding Decoder (DeTokenize). There are already many multimodal works based on this “Image Tokenizer” idea, such as the recent LWM and AnyGPT.

Whether in the original pixel space or the compressed encoding space, they share a common characteristic: they are both 2D features. In other words, text has only one dimension (left-to-right), while images have two (left-to-right, top-to-bottom). When performing autoregressive generation, one must manually design the generation direction—such as left-to-right then top-to-bottom, top-to-bottom then left-to-right, counter-clockwise from the center, or sorted by distance to the top-left corner. Different generation directions may significantly affect the results, introducing extra hyperparameters and making the process feel less elegant because it is not fully end-to-end. To address this, we can use Cross Attention to combine 2D features and output encoding results in a single direction. Related work can be found in “Planting a SEED of Vision in Large Language Model”.

Compression Loss

It seems that through the “Image Tokenizer” approach, multimodal generation is “solved”? Not quite; the problems are just beginning.

The biggest problem with Image Tokenizers like VQ-VAE and VQ-GAN is that to significantly increase generation speed and shorten sequence length, the encoding resolution is highly compressed (mainstream is 256\times 256 \to 32\times 32 or even 256\times 256 \to 16\times 16). This leads to a severe loss of image information. To perceive this intuitively, we can refer to the reconstruction effect in the SEED paper:

As we can see, although the reconstructed images are indeed clear and maintain the overall semantics of the input, the local details are completely different. This means it is impossible to complete arbitrary mixed image-text tasks (such as OCR) based on this Image Tokenizer.

Furthermore, a simple information calculation reveals how serious the information loss is. First, referring to the experimental results of “Generating Long Sequences with Sparse Transformers”, we know that the average information entropy of ImageNet-64 is 3.44 bits/byte. The models then were not large enough; theoretically, increasing the model size could further reduce this number. Let’s assume it is 3 bits/byte. Then a 64\times 64 ImageNet image has an average total information entropy of 64\times 64\times 3\times 3 bits. Next, we know that for a vocabulary of size V, the average information entropy of each token is \log_2 V bits. If we want to compress the encoding length to L and achieve lossless compression, we must have: \begin{equation} L\times \log_2 V \geq 64\times 64\times 3\times 3 \end{equation} If L=1024=32\times 32, then we need at least V \geq 2^{36} \approx 7\times 10^{10}. If L=256=16\times 16, it requires V \geq 2^{144} \approx 2\times 10^{43}! Obviously, the codebook sizes of current Image Tokenizers have not reached such astronomical levels, so the result is inevitably severe information loss!

A natural question is: Why must it be lossless? Indeed, humans cannot achieve lossless perception either; in fact, human understanding of images might involve even more severe information loss than an Image Tokenizer. But the problem is that the most basic requirement for a model is to align with human cognition. In other words, lossy compression is fine as long as it is lossless to humans—just as discarding infrared and ultraviolet light is completely lossless to the human eye. However, “lossless to humans” is a very broad concept with no computable metrics. VQ-VAE uses L2 distance to reconstruct images; due to information loss, blurring is inevitable. VQ-GAN added GAN loss to improve clarity, but it can only maintain global semantics and cannot fully align with human standards. Moreover, no one knows when humans will propose new image tasks that rely more on details. Therefore, from the perspective of general intelligence, lossless compression is the inevitable final choice.

From this, it is clear that in a truly general multimodal model, the image part will inevitably be much more difficult than the text part because the information content of images is far greater than that of text. But in reality, images created by humans (like painting) are not much more complex than text (like writing). Truly complex images are photographs taken directly from nature. Ultimately, text is a product of humans, while images are products of nature. Humans are not as smart as nature, so text is not as difficult as images. Truly general artificial intelligence is meant to move in the direction of completely surpassing humans.

Diffusion Models

Back to the point. Regarding current image generation technology, if we restrict ourselves to lossless compression, we either return to autoregression in pixel space—which, as analyzed, is unacceptably slow—or the only remaining choice is to return to continuous space. Treating images as continuous vectors under the constraint of lossless compression, the only two choices are Flow models and Diffusion models.

Flow is designed to be reversible, and Diffusion models can also

derive reversible ODE equations. Both map a standard Gaussian

distribution to the target distribution, meaning they have sufficient

entropy sources. Discrete and continuous

generation differ: the entropy source for discrete autoregressive

generation is seqlen and vocab_size. Since the

contribution of vocab_size grows logarithmically, it mainly

relies on seqlen. However, seqlen is

equivalent to cost, so the entropy source for discrete models is

expensive. The entropy source for transformation-based continuous

generation is Gaussian noise, which in principle is inexhaustible,

cheap, and parallelizable. However, to ensure reversibility in

every layer, Flow requires significant architectural modifications that

might limit its performance ceiling (there is no direct evidence, but

Flow models haven’t produced stunning results). Thus, the only remaining

choice is Diffusion.

Note that Diffusion is just a choice for the image generation scheme. For image understanding, from a lossless perspective, any encoding method carries the risk of distortion, so the most reliable input is the original image itself. Therefore, the safest way should be to input the original image directly in the form of patches, similar to the approach of Fuyu-8b:

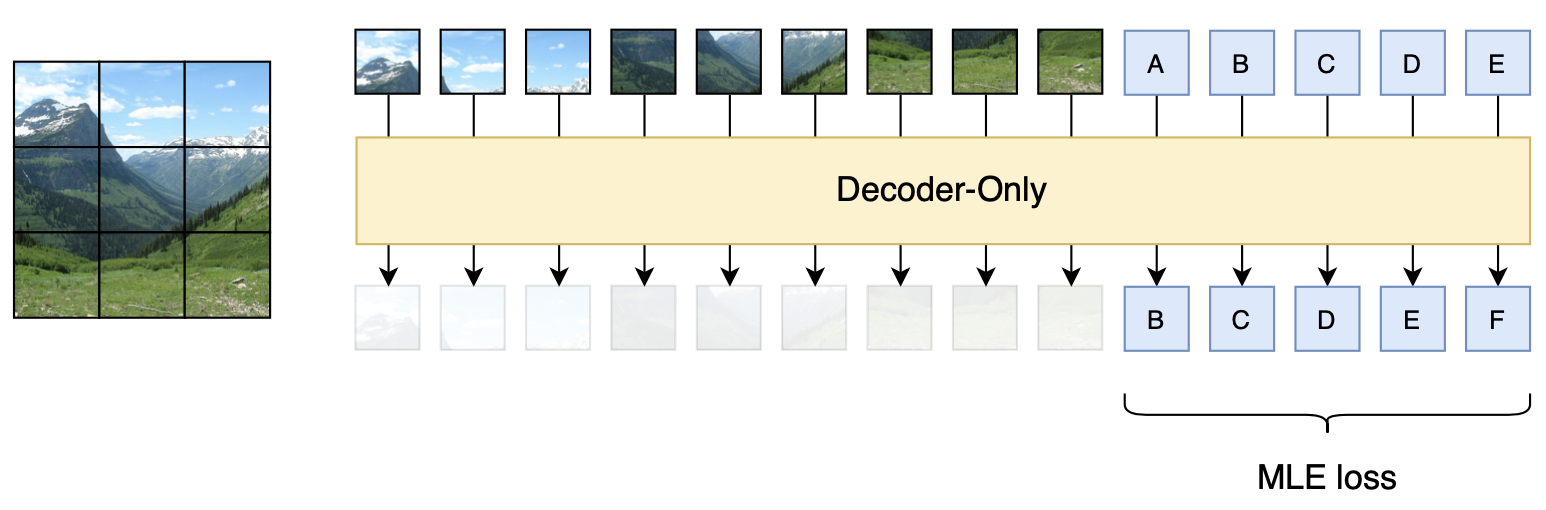

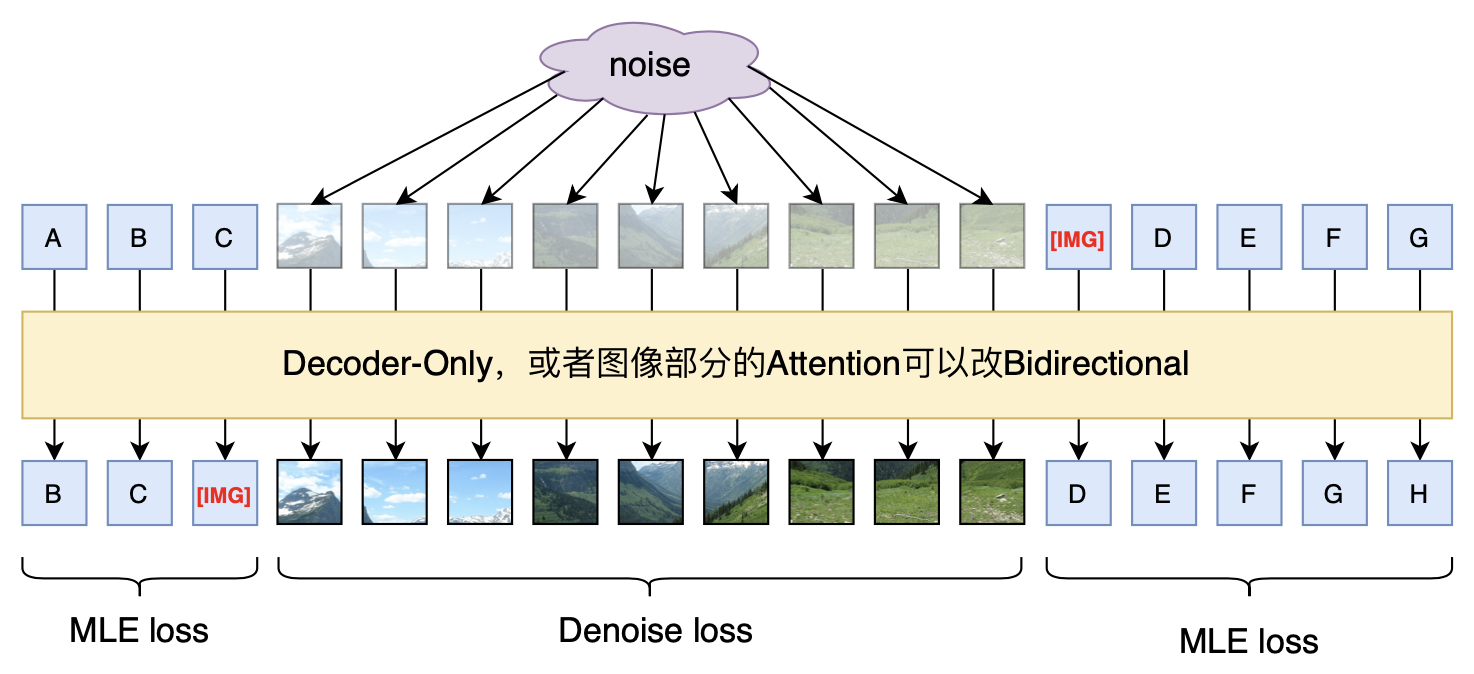

However, Fuyu-8b only has multimodal input; its output is unimodal text. How can we add image generation capability to it? Considering that the training phase of a Diffusion model is a denoising task, a possible approach is:

During the training phase, input text and noisy images. The training

objective for text is to predict the next token, and for images, it is

to predict the original image (or noise). For inference, the text part

is still decoded recursively token by token until [IMG] is

predicted. Then, several noise vectors are input in parallel, and the

image is sampled according to the Diffusion model. Note that the image

generation part is parallel, so in principle, it is better not to be

Decoder-Only, because if it were, one would have to manually specify an

ordering, and different orderings might significantly affect the

results. With current Diffusion acceleration techniques, image

generation can be completed in about 10 steps, so the generation speed

is acceptable.

(Update 2024.08.26: Meta’s new Transfusion is basically the same as the above scheme, except it adds a Latent Encoder step for images, with excellent results; additionally, the slightly later Show-o is also very similar, with the difference being that it also discretizes Diffusion.)

Patch Input

A key part of the above approach is using a Patch-based Diffusion model, so the most basic step is to verify whether such a Diffusion model design is feasible (since there were claims that Diffusion models rely heavily on the existing U-Net architecture). To this end, I conducted some experiments and surveyed some literature. Below is a summary of my preliminary conclusions.

According to the materials I found, the earliest works attempting to combine “Patch input + Transformer” for Diffusion models should be “All are Worth Words: A ViT Backbone for Diffusion Models” and “Scalable Diffusion Models with Transformers”. Both papers appeared around the same time and used similar methods. The former (U-ViT) emphasized the role of “Long skip connections” from U-Net, while the latter (DiT) emphasized the necessity of incorporating the Diffusion time t and condition label y into the model via adaLN. However, only U-ViT attempted to use raw image patches as input directly, and only at a resolution of 64\times 64. For 256\times 256 and 512\times 512 resolutions, both U-ViT and DiT performed diffusion in the feature space after dimensionality reduction by an LDM autoencoder. This is indeed the current mainstream practice, but as mentioned before, this level of compression comes with severe information loss, making it hard to call these truly general features.

Using raw image patches instead of pre-trained encoder features as input also has the benefit of avoiding feature isolation. For example, when we need to input two images I_1, I_2 simultaneously, the usual approach based on encoder features is to input encoder(I_1), encoder(I_2) into the model. The problem is that the encoder itself has already performed a layer of interaction within the image semantics. If we input encoder(I_1), encoder(I_2), the interaction between I_1 and I_2 lacks this layer. This is the problem of feature isolation between images; more details can be found in “Browse and Concentrate: Comprehending Multimodal Content via prior-LLM Context Fusion”. Therefore, it is better to input both text and images in their original forms and let the multimodal model decide all interactions itself, thus eliminating this barrier.

Of course, the practice of directly inputting raw image patches has not become mainstream, which implies there must be difficulties. I experimented with this myself. The task was Diffusion generation on CelebA-HQ at resolutions of 64\times 64 and 128\times 128, reshaped into 16\times 16\times 48 and 16\times 16\times 192 respectively and projected into the model. The model was a standard Pre-Norm Transformer without Long skip connections. The backbone was GAU instead of MHA. The position encoding was 2D-RoPE, and the time embedding was added directly to the patch input. The code can be found here:

Link: https://github.com/bojone/Keras-DDPM/blob/main/ddpm-gau.py

My experimental results show that for both 64\times 64 and 128\times 128 resolutions, they can indeed converge normally and eventually generate effects similar to a standard U-Net (I didn’t calculate FID, just visual inspection). However, it requires more training steps to converge. For instance, on a single A800, a standard U-Net takes about 1–2 days to produce decent results at 128\times 128, while the Transformer-based architecture takes more than 10 days to be barely acceptable. The reason is likely the lack of CNN’s inductive bias; the model needs more training steps to learn to adapt to image priors. However, for large multimodal models, this is probably not a problem because the number of training steps required for LLMs is already sufficiently large.

Summary

This article introduced my conception of multimodal model design—directly using raw image patches as image input, with the text part following conventional next-token prediction and the image part using noisy image input to reconstruct the original image. This combination theoretically achieves multimodal generation in the most high-fidelity way. Preliminarily, it is possible for a Transformer using raw image patches as input to train a successful image Diffusion model. Thus, this model design mixing Diffusion and text has the potential for success. Of course, these are just some rough ideas of mine regarding the multimodal path, most of which have not been verified through practice. Please read with discretion.

Original URL: https://kexue.fm/archives/9984