In Making Alchemy More Scientific (V): Tuning Learning Rates Based on Gradients, we entered a new chapter on scheduling learning rates based on gradients. However, as mentioned at the end of the previous article, we encountered difficulties in proving the optimal learning rate for the final loss under dynamic gradients. Specifically, the optimal learning rate sequence we "guessed" using the calculus of variations is extremely difficult to verify through scaling when substituted back into the conclusions. Consequently, let alone the optimal solution, we could not even determine if the sequence was a feasible solution.

In this article, we will obtain more precise conclusions through an exquisite construction, thereby solving this problem. Judging by the proof process, the precision of this conclusion may have reached a point where it cannot be further improved. This breakthrough also originates from the paper "Optimal Linear Decay Learning Rate Schedules and Further Refinements".

Problem Review

Let us first revisit the previous conclusions. At the end of the last article, we obtained a general version of the conclusion from Making Alchemy More Scientific (IV): New Identity, New Learning Rate: \begin{equation} \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_T) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] \leq \frac{R^2}{2\eta_{1:T}} + \frac{1}{2}\sum_{t=1}^T\frac{\eta_t^2 G_t^2}{\eta_{\min(t+1, T):T}}\label{leq:last-2} \end{equation} We want to find the sequence \eta_1, \eta_2, \dots, \eta_T \geq 0 that minimizes the right-hand side of the above equation. Through continuous approximation and the calculus of variations, we "guessed" the answer to be: \begin{equation} \eta_t = \frac{R G_t^{-2}}{\sqrt{Q_T}} (1 - Q_t/Q_T)\label{eq:opt-lr-last-x} \end{equation} where Q_t = \sum_{k=1}^t G_k^{-2}. However, we could not substitute it back to prove it, or rather, proving it would require additional assumptions. If we try to substitute it, we find the main problem is that the denominator on the right side of Eq. [leq:last-2] is \eta_{t+1:T} (when t < T), making it impossible to guarantee that \eta_t / \eta_{t+1:T} is bounded, which makes various scalings difficult. If we could further improve the denominator on the right side of the conclusion to \eta_{t:T}, the proof would follow naturally.

This article completes the final proof by further improving the precision of conclusion [leq:last-2], but not by directly and explicitly improving it. Instead, through careful scaling, we construct the optimal learning rate sequence from the top down, thereby achieving the effect of implicitly improving precision.

Careful Scaling

Specifically, our starting point is the identity from Making Alchemy More Scientific (IV): New Identity, New Learning Rate: \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} q_T =&\, \frac{1}{w_{1:T}}\sum_{t=1}^T w_t q_t + \sum_{k=1}^{T-1}\left(\frac{1}{w_{k+1:T}} - \frac{1}{w_{k:T}}\right)\sum_{t=k}^T w_t (q_t - q_k) \\ =&\, \frac{1}{w_{1:T}}\sum_{t=1}^T w_t q_t + \sum_{k=1}^{T-1}\left(\frac{1}{w_{k+1:T}} - \frac{1}{w_{k:T}}\right)\sum_{t=k+1}^T w_t (q_t - q_k) \end{aligned}\label{eq:qt-g} \end{equation} We let q_t = \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)], where \mathbb{E} is the expectation over all \boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_T. Substituting this into the above equation gives: \begin{equation} \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_T) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] = \frac{1}{w_{1:T}}\sum_{t=1}^T w_t \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] + \sum_{k=1}^{T-1}\left(\frac{1}{w_{k+1:T}} - \frac{1}{w_{k:T}}\right)\sum_{t=k+1}^T w_t \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_k)]\label{eq:qt-g2} \end{equation} From now on, we must keep in mind the principle of "no scaling unless necessary" to achieve the highest possible precision. Now we use convexity for the first scaling: \begin{gather} \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] = \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t) - L(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] \leq \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] \\[4pt] \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_k)] = \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t) - L(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_k)] \leq \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}_k)] \end{gather} Note that this requires each \boldsymbol{\theta}_t to depend at most on \boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}, which is satisfied in stochastic optimization. Also, the first equality in the second line requires t \geq k, which is obviously satisfied. Substituting into Eq. [eq:qt-g2] yields: \begin{equation} \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_T) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] \leq \underbrace{\frac{1}{w_{1:T}}\sum_{t=1}^T w_t \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}^*)]}_{(\text{A})} + \underbrace{\sum_{k=1}^{T-1}\left(\frac{1}{w_{k+1:T}} - \frac{1}{w_{k:T}}\right)\sum_{t=k+1}^T w_t \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}_k)]}_{(\text{B})}\label{leq:last-6-mid} \end{equation} In the article Making Alchemy More Scientific (IV): New Identity, New Learning Rate, the next step was to scale (\text{A}) and (\text{B}) in [leq:last-6-mid] separately and then add them. Scaling them separately amplified the error and caused trouble for subsequent proofs.

Identity Transformation

Therefore, in this section, we will merge them into a single expression through identity transformations before considering scaling, in order to achieve higher precision. First, assuming the learning rate is independent of the data \boldsymbol{x}_t, we can move the expectation \mathbb{E} outside: \begin{equation} \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_T) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] \leq \mathbb{E}\Bigg[\underbrace{\frac{1}{w_{1:T}}\sum_{t=1}^T w_t \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}^*)}_{(\text{A})} + \underbrace{\sum_{k=1}^{T-1}\left(\frac{1}{w_{k+1:T}} - \frac{1}{w_{k:T}}\right)\sum_{t=k+1}^T w_t \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}_k)}_{(\text{B})}\Bigg] \end{equation} The more complex part is the second term. Using \sum_{k=1}^{T-1}\sum_{t=k+1}^T = \sum_{t=1}^T \sum_{k=1}^{t-1} to swap the order of summation, we get: \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} (\text{B}) =&\, \sum_{t=1}^T \sum_{k=1}^{t-1}\left(\frac{1}{w_{k+1:T}} - \frac{1}{w_{k:T}}\right) w_t \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot(\boldsymbol{\theta}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}_k) \\ =&\, \sum_{t=1}^T w_t \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot \sum_{k=1}^{t-1}\left(\frac{1}{w_{k+1:T}} - \frac{1}{w_{k:T}}\right) (\boldsymbol{\theta}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}_k) \\ =&\, \sum_{t=1}^T w_t \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot \left(\left(\frac{1}{w_{t:T}} - \frac{1}{w_{1:T}}\right)\boldsymbol{\theta}_t - \sum_{k=1}^{t-1}\left(\frac{1}{w_{k+1:T}} - \frac{1}{w_{k:T}}\right) \boldsymbol{\theta}_k\right) \\ \end{aligned} \end{equation} After adding (\text{A}), the term \frac{1}{w_{1:T}}w_t \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot\boldsymbol{\theta}_t is exactly cancelled out. Rearranging the remaining terms gives: \begin{equation} \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_T) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] \leq \mathbb{E}\Bigg[\frac{1}{w_{1:T}}\sum_{t=1}^T w_t \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot\Bigg(\underbrace{\frac{w_{1:T}}{w_{t:T}}\boldsymbol{\theta}_t - w_{1:T}\sum_{k=1}^{t-1}\left(\frac{1}{w_{k+1:T}} - \frac{1}{w_{k:T}}\right) \boldsymbol{\theta}_k}_{\text{denoted as }\boldsymbol{\psi}_t} - \boldsymbol{\theta}^*\Bigg)\Bigg] \end{equation} As long as we denote the indicated part as \boldsymbol{\psi}_t, the right-hand side takes the standard form of (weighted) average loss convergence: \begin{equation} \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_T) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] \leq \mathbb{E}\Bigg[\frac{1}{w_{1:T}}\sum_{t=1}^T w_t \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot(\boldsymbol{\psi}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}^*)\Bigg] = \frac{1}{w_{1:T}}\sum_{t=1}^T w_t \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot(\boldsymbol{\psi}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}^*)]\label{leq:last-6-mid2} \end{equation}

Update Rules

According to the definition of \boldsymbol{\psi}_t, it can be directly verified that: \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\psi}_{t+1} - \boldsymbol{\psi}_t = \frac{w_{1:T}}{w_{t+1:T}}(\boldsymbol{\theta}_{t+1} - \boldsymbol{\theta}_t) \end{equation} Therefore, if we let \boldsymbol{\psi}_t update according to \boldsymbol{\psi}_{t+1} = \boldsymbol{\psi}_t - w_t \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t), then we will have \boldsymbol{\theta}_{t+1} = \boldsymbol{\theta}_t - \frac{w_t w_{t+1:T}}{w_{1:T}} \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t): \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\psi}_{t+1} = \boldsymbol{\psi}_t - w_t \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\qquad\Rightarrow\qquad\boldsymbol{\theta}_{t+1} = \boldsymbol{\theta}_t - \frac{w_t w_{t+1:T}}{w_{1:T}} \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t) \end{equation} For \boldsymbol{\psi}_t updated according to this rule, we have already proven in Making Alchemy More Scientific (II): Extending Conclusions to Unbounded Domains and Making Alchemy More Scientific (V): Tuning Learning Rates Based on Gradients that the following inequality holds: \begin{equation} \frac{1}{w_{1:T}}\sum_{t=1}^T w_t \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\cdot(\boldsymbol{\psi}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] \leq \frac{1}{2 w_{1:T}}\left(R^2 + \sum_{t=1}^T w_t^2 \mathbb{E}[\Vert\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\Vert^2]\right)\label{leq:avg-3} \end{equation} where R = \Vert\boldsymbol{\psi}_1 - \boldsymbol{\theta}^*\Vert. If we choose the same starting point for \boldsymbol{\psi}_t and \boldsymbol{\theta}_t, then we also have R = \Vert\boldsymbol{\theta}_1 - \boldsymbol{\theta}^*\Vert.

Some readers might find this suspicious: the \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t) in the above formula is the gradient at \boldsymbol{\theta}_t rather than at \boldsymbol{\psi}_t. Can it be substituted into the previous conclusion? In Making Alchemy More Scientific (V): Tuning Learning Rates Based on Gradients, we specifically explained that the role of using the gradient at the current point \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\psi}_t) is to establish the relationship between \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\psi}_t)\cdot(\boldsymbol{\psi}_t - \boldsymbol{\theta}^*) and the loss function through convexity. However, that relationship is not needed here, so replacing it with \boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t) is acceptable.

Strongest Conclusion

Now, substituting conclusion [leq:avg-3] into Eq. [leq:last-6-mid2] and performing the second scaling, we get: \begin{equation} \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_T) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] \leq \frac{1}{2 w_{1:T}}\left(R^2 + \sum_{t=1}^T w_t^2 G_t^2\right)\label{leq:last-6} \end{equation} Here we denote G_t^2 = \mathbb{E}[\Vert\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\Vert^2]. In other words, if we use the learning rate \eta_t = \frac{w_t w_{t+1:T}}{w_{1:T}} to execute SGD, its final loss satisfies the above inequality. Because the scaling was performed more carefully, this upper bound is theoretically more accurate than conclusion [leq:last-2], but it is somewhat implicit because it requires us to first solve for w_t from \eta_t before substituting it into the right-hand side for verification. However, solving for w_t explicitly is not a trivial matter.

However, we can work backwards: derive the optimal w_t, and then obtain the optimal \eta_t from \eta_t = \frac{w_t w_{t+1:T}}{w_{1:T}}. We already found the minimum of the right-hand side in the previous article Making Alchemy More Scientific (V): Tuning Learning Rates Based on Gradients. The answer is: \begin{equation} w_t = \frac{R G_t^{-2}}{\sqrt{Q_T}},\qquad Q_T=\sum_{k=1}^T G_k^{-2} \end{equation} Then the optimal \eta_t is: \begin{equation} \eta_t = \frac{w_t w_{t+1:T}}{w_{1:T}} = \frac{R G_t^{-2}}{\sqrt{Q_T}} (1 - Q_t/Q_T)\label{eq:opt-lr-last-x2} \end{equation} This is exactly Eq. [eq:opt-lr-last-x]! Thus, we have completed the proof of the optimality of Eq. [eq:opt-lr-last-x].

Regarding this result itself, we provided a preliminary interpretation in the previous article: the first term G_t^{-2} is inversely proportional to the square of the gradient norm, which explains the necessity of an early Warmup, as early gradients are usually large; 1 - Q_t/Q_T decays monotonically to zero, explaining the necessity of learning rate decay. In particular, if we assume the gradient norm is constant, we obtain a linear decay learning rate, which is a commonly used strategy in practice.

Post-hoc Adjustment

How else can Eq. [eq:opt-lr-last-x2] guide practice? First, it does not comply with causality and cannot be used directly. The original paper "Optimal Linear Decay Learning Rate Schedules and Further Refinements" provides a post-hoc verification/adjustment approach.

The idea is simple: first, choose any learning rate strategy and train once. Then, use the gradient information to calculate the optimal learning rate [eq:opt-lr-last-x2] and see if its curve matches our chosen strategy. If there is a significant deviation, the learning rate strategy needs to be adjusted and the training repeated. This is referred to as "Refinement" in the paper. This approach is suitable for scenarios where many preliminary experiments are conducted before formal training.

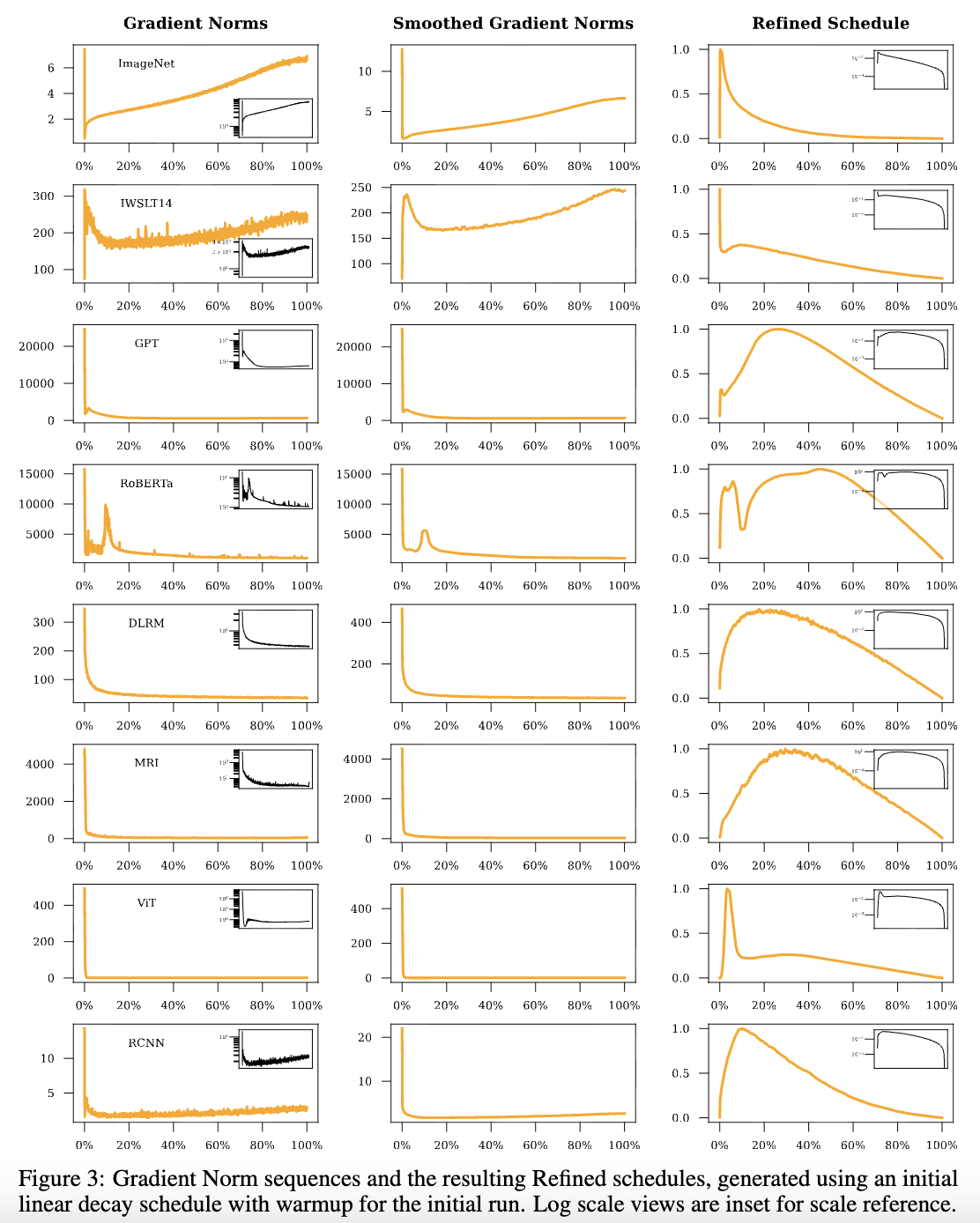

The paper provides some examples of Refined learning rates, most of which take a "Warmup-Decay" form. Notably, in most experiments, the gradient norm in the middle and late stages is nearly constant, so the optimal Decay shape in those stages is close to linear decay:

Finally, the above results are for SGD, where w_t \propto \mathbb{E}[\Vert\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\Vert^{-2}]. In practice, we can only approximate this with \Vert\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\Vert^2, where \Vert\cdot\Vert is the L2 norm. For adaptive learning rate optimizers like Adam, the paper suggests using w_t \propto \mathbb{E}[\Vert\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\Vert_1^{-1}], which is inversely proportional to the L1 norm. We will discuss adaptive learning rate optimizers in future articles.

Explicit Version

If we specify our own learning rate strategy \eta_t and want to see how optimal it is, it currently seems quite troublesome because Eq. [leq:last-6] is a semi-implicit conclusion. To substitute it into the right-hand side for verification, one must solve the equation \eta_t = \frac{w_t w_{t+1:T}}{w_{1:T}}. This equation is not necessarily hard to solve, but the solution is not concise, making it difficult to use the exact solution for proof.

Here, through further scaling, we transform it into an explicit conclusion regarding \eta_t. The scaling requires some skill; I thought about it for a long time, but it is quite understandable once written out: \begin{equation} \eta_t = \frac{w_t w_{t+1:T}}{w_{1:T}} \leq \frac{w_t (w_{t:T} + w_{t+1:T})}{2 w_{1:T}} = \frac{w_{t:T}^2 - w_{t+1:T}^2}{2 w_{1:T}} \end{equation} Here w_{t:T}^2 is understood as (w_{t:T})^2. Summing both sides from t to T, we get: \begin{equation} \eta_{t:T} \leq \frac{w_{t:T}^2}{2 w_{1:T}} \end{equation} Substituting t=1 yields \frac{1}{w_{1:T}} \leq \frac{1}{2\eta_{1:T}}. Then, replacing t with t+1 yields \frac{w_{1:T}}{w_{t+1:T}^2} \leq \frac{1}{2\eta_{t+1:T}}. Combining this with the definition of \eta_t, we get \frac{w_t^2}{w_{1:T}} = \eta_t^2 \frac{w_{1:T}}{w_{t+1:T}^2} \leq \frac{\eta_t^2}{2\eta_{t+1:T}}. Finally, slightly transforming the right side of Eq. [leq:last-6] and substituting these inequalities gives: \begin{equation} \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_T) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] \leq \frac{R^2}{2 w_{1:T}} + \sum_{t=1}^T \frac{w_t^2}{2 w_{1:T}} G_t^2 \leq \frac{R^2}{4 \eta_{1:T}} + \sum_{t=1}^{T-2} \frac{\eta_t^2}{4\eta_{t+1:T}} G_t^2 + \frac{w_{T-1}^2}{2 w_{1:T}} G_{T-1}^2 + \frac{w_T^2}{2 w_{1:T}} G_T^2 \end{equation} We did not scale the last two terms because, according to the definition \eta_t = \frac{w_t w_{t+1:T}}{w_{1:T}}, we must have \eta_T=0, which means \frac{\eta_t^2}{2\eta_{t+1:T}} would be infinite at t=T-1 and t=T. This also tells us that \eta_1, \eta_2, \dots, \eta_T actually only have T-1 free parameters, while the corresponding "unknowns" w_1, w_2, \dots, w_T number T. The number of equations is less than the number of unknowns, which provides us with a degree of freedom for flexible adjustment.

Again, by definition, we have \eta_{T-1} = \frac{w_{T-1} w_T}{w_{1:T}}. Thus, from the AM-GM inequality: \begin{equation} \frac{w_{T-1}^2}{2 w_{1:T}} G_{T-1}^2 + \frac{w_T^2}{2 w_{1:T}}G_T^2 \geq \frac{w_{T-1} w_T}{w_{1:T}} G_{T-1}G_T = \eta_{T-1}G_{T-1}G_T \end{equation} Due to the existence of the "flexible degree of freedom," we can choose appropriate w_{T-1}, w_T (i.e., let w_{T-1} G_{T-1} = w_T G_T) such that the above inequality becomes an equality. Thus: \begin{equation} \mathbb{E}[L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_T) - L(\boldsymbol{\theta}^*)] \leq \frac{R^2}{4 \eta_{1:T}} + \sum_{t=1}^{T-2} \frac{\eta_t^2}{4\eta_{t+1:T}} G_t^2 + \eta_{T-1} G_{T-1} G_T \end{equation} I have not found this conclusion in any literature, so for now, I consider it new. Its precision is higher than [leq:last-2]. Of course, conclusion [leq:last-2] is not actually applicable to learning rate sequences that end at 0, so they are not easy to compare directly. However, looking at the constant coefficients of the first two main terms, [leq:last-2] has 1/2 while the above formula has 1/4, suggesting that on average, the precision should be twice as high.

Summary

At the end of the previous article, we mentioned the difficulty in proving the optimal learning rate strategy for the final loss. In this article, through top-down, careful scaling and construction, we completed this proof and obtained a higher-precision result. We also discussed the inspiration this result provides for the "Warmup-Decay" mechanism of learning rates.

When reprinting, please include the original address of this article: https://kexue.fm/archives/11540

For more detailed reprinting matters, please refer to: "Scientific Space FAQ"