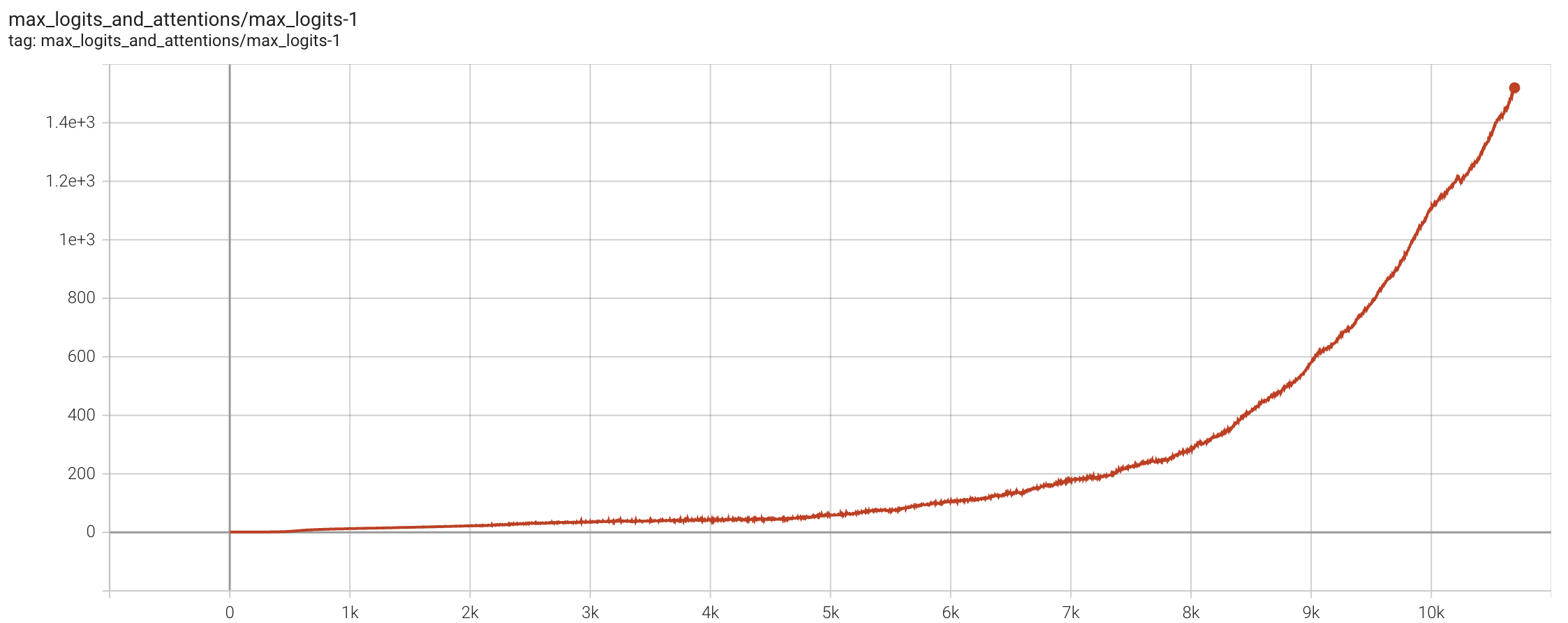

Four months ago, we released Moonlight, verifying the effectiveness of the Muon optimizer on a 16B MoE model. In Moonlight, we confirmed the necessity of adding Weight Decay to Muon and proposed a technique for migrating Adam hyperparameters through Update RMS alignment, which allowed Muon to be quickly applied to LLM training. However, when we attempted to further extend Muon to models with over 100 billion parameters, we encountered a new "stumbling block"—MaxLogit explosion.

To solve this problem, we propose a simple but extremely effective new method called "QK-Clip." This method addresses the MaxLogit phenomenon from a very fundamental perspective without sacrificing model performance. It has become one of the key training technologies for our recently released trillion-parameter model, "Kimi K2."

Problem Description

Let’s first briefly introduce the MaxLogit explosion phenomenon. Recall the definition of Attention: \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{O} = \text{softmax}(\boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{K}^{\top})\boldsymbol{V} \end{equation} Here, the scaling factor 1/\sqrt{d} is omitted because it can always be absorbed into the definitions of \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K}. The "Logit" in "MaxLogit explosion" refers to the Attention matrix before Softmax, i.e., \boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{K}^{\top}, and MaxLogit refers to the maximum value of all logits, which we denote as: \begin{equation} S_{\max} = \max_{i,j}\, \boldsymbol{q}_i\cdot \boldsymbol{k}_j \end{equation} This \max is actually also taken over the batch_size dimension, ultimately resulting in a scalar. MaxLogit explosion refers to the phenomenon where S_{\max} continues to rise as training progresses, with a growth rate that is linear or even super-linear, showing no signs of stabilization for a long period.

MaxLogit is essentially an indicator of outliers. Its explosion means that outliers have exceeded controllable ranges. Specifically, we have: \begin{equation} |\boldsymbol{q}_i\cdot \boldsymbol{k}_j| \leq \Vert\boldsymbol{q}_i\Vert \Vert\boldsymbol{k}_j\Vert = \Vert\boldsymbol{x}_i\boldsymbol{W}_q\Vert \Vert\boldsymbol{x}_j\boldsymbol{W}_k\Vert \leq \Vert\boldsymbol{x}_i\Vert \Vert\boldsymbol{x}_j\Vert \Vert\boldsymbol{W}_q\Vert \Vert\boldsymbol{W}_k\Vert \label{eq:kexi} \end{equation} Since \boldsymbol{x} is usually processed with RMSNorm, \Vert\boldsymbol{x}_i\Vert \Vert\boldsymbol{x}_j\Vert generally does not explode. Therefore, MaxLogit explosion implies a risk that the spectral norms \Vert\boldsymbol{W}_q\Vert and \Vert\boldsymbol{W}_k\Vert are heading towards infinity, which is clearly not good news.

Since even very large values become less than 1 after Softmax, in lucky cases, this phenomenon might not lead to severe consequences beyond wasting an Attention Head. However, in worse cases, it can cause Gradient Spikes or even training collapse. Therefore, to be safe, one should try to avoid the occurrence of MaxLogit explosion.

Existing Attempts

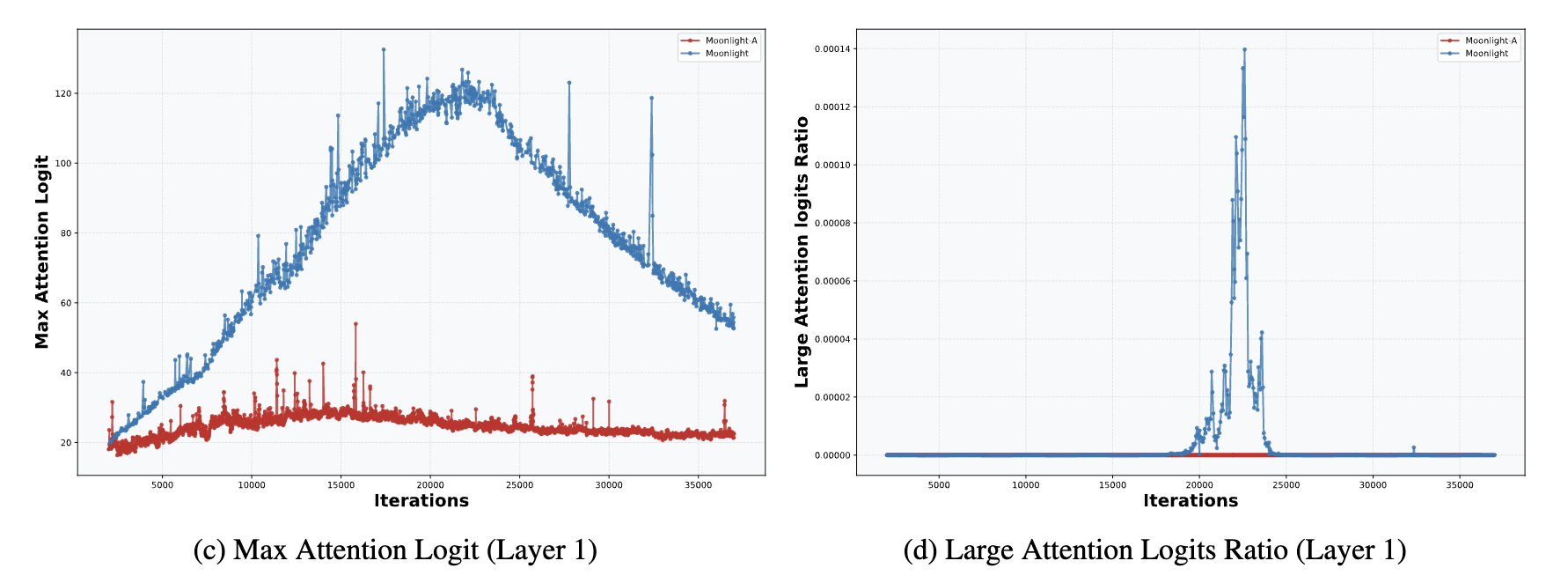

In "Muon Sequel: Why We Chose to Try Muon?", we briefly analyzed that Weight Decay can prevent MaxLogit explosion to some extent. Thus, the probability of MaxLogit explosion in small models is low; even in a 16B model like Moonlight, MaxLogit rose to at most 120 before automatically decreasing.

In other words, MaxLogit explosion occurs more frequently in models with very large parameter counts. The larger the model, the more instability factors there are in training, and the harder it is for Weight Decay to stabilize training. Increasing Weight Decay at this point could naturally strengthen control, but it would also lead to significant performance loss, so this path is blocked. Another direct idea is to add a \text{softcap} to the Logits: \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{O} = \text{softmax}(\text{softcap}(\boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{K}^{\top};\tau))\boldsymbol{V} \end{equation} where \text{softcap}(x;\tau) = \tau\tanh(x/\tau), introduced by Google’s Gemma 2. Due to the boundedness of \tanh, \text{softcap} naturally ensures that the Logits after \text{softcap} are bounded. However, it cannot guarantee that the Logits before \text{softcap} are bounded (as verified by our tests). Thus, \text{softcap} merely transforms one problem into another without actually solving it.

Perhaps Google realized this as well, as they stopped using \text{softcap} in the later Gemma 3 and switched to "QK-Norm": \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{O} = \text{softmax}(\tilde{\boldsymbol{Q}}\tilde{\boldsymbol{K}}{}^{\top})\boldsymbol{V},\quad \begin{aligned} \tilde{\boldsymbol{Q}}=&\,\text{RMSNorm}(\boldsymbol{Q}) \\ \tilde{\boldsymbol{K}}=&\,\text{RMSNorm}(\boldsymbol{K}) \end{aligned} \end{equation}

QK-Norm is indeed an effective method for suppressing MaxLogit. However, it is only applicable to MHA, GQA, etc., and not to MLA (Multi-Head Latent Attention). This is because QK-Norm requires materializing \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K}, but for MLA, the \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K} during the training phase are different from those in the decoding phase (as shown below). In the decoding phase, we cannot fully materialize the \boldsymbol{K} from the training phase; in other words, QK-Norm cannot be performed during decoding.

\begin{array}{c|c} \text{Training/Prefill} & \text{Decoding} \\ \hline \begin{gathered} \boldsymbol{o}_t = \left[\boldsymbol{o}_t^{(1)}, \boldsymbol{o}_t^{(2)}, \dots, \boldsymbol{o}_t^{(h)}\right] \\[10pt] \boldsymbol{o}_t^{(s)} = \frac{\sum_{i\leq t}\exp\left(\boldsymbol{q}_t^{(s)} \boldsymbol{k}_i^{(s)}{}^{\top}\right)\boldsymbol{v}_i^{(s)}}{\sum_{i\leq t}\exp\left(\boldsymbol{q}_t^{(s)} \boldsymbol{k}_i^{(s)}{}^{\top}\right)} \\[15pt] \boldsymbol{q}_i^{(s)} = \left[\boldsymbol{x}_i\boldsymbol{W}_{qc}^{(s)},\boldsymbol{x}_i\boldsymbol{W}_{qr}^{(s)}\textcolor[HTML]{3CE2F7}{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_i}\right]\in\mathbb{R}^{d_k + d_r}\\ \boldsymbol{k}_i^{(s)} = \left[\boldsymbol{c}_i\boldsymbol{W}_{kc}^{(s)},\boldsymbol{x}_i\boldsymbol{W}_{kr}^{\cancel{(s)}}\textcolor[HTML]{3CE2F7}{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_i}\right]\in\mathbb{R}^{d_k + d_r} \\ \boldsymbol{v}_i^{(s)} = \boldsymbol{c}_i\boldsymbol{W}_v^{(s)}\in\mathbb{R}^{d_v},\quad\boldsymbol{c}_i = \boldsymbol{x}_i \boldsymbol{W}_c\in\mathbb{R}^{d_c} \end{gathered} & \begin{gathered} \boldsymbol{o}_t = \left[\boldsymbol{o}_t^{(1)}\boldsymbol{W}_v^{(1)}, \boldsymbol{o}_t^{(2)}\boldsymbol{W}_v^{(2)}, \dots, \boldsymbol{o}_t^{(h)}\boldsymbol{W}_v^{(h)}\right] \\[10pt] \boldsymbol{o}_t^{(s)} = \frac{\sum_{i\leq t}\exp\left(\boldsymbol{q}_t^{(s)} \boldsymbol{k}_i^{\cancel{(s)}}{}^{\top}\right)\boldsymbol{v}_i^{\cancel{(s)}} }{\sum_{i\leq t}\exp\left(\boldsymbol{q}_t^{(s)} \boldsymbol{k}_i^{\cancel{(s)}}{}^{\top}\right)} \\[15pt] \boldsymbol{q}_i^{(s)} = \left[\boldsymbol{x}_i\boldsymbol{W}_{qc}^{(s)}\boldsymbol{W}_{kc}^{(s)}{}^{\top}, \boldsymbol{x}_i\boldsymbol{W}_{qr}^{(s)}\textcolor[HTML]{3CE2F7}{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_i}\right]\in\mathbb{R}^{d_c + d_r}\\ \boldsymbol{k}_i^{\cancel{(s)}} = \left[\boldsymbol{c}_i, \boldsymbol{x}_i\boldsymbol{W}_{kr}^{\cancel{(s)}}\textcolor[HTML]{3CE2F7}{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_i}\right]\in\mathbb{R}^{d_c + d_r}\\ \boldsymbol{v}_i^{\cancel{(s)}} = \boldsymbol{c}_i= \boldsymbol{x}_i \boldsymbol{W}_c\in\mathbb{R}^{d_c} \end{gathered} \\ \end{array}

Why use MLA? We have discussed this in two articles: "Transformer Upgrade: 21. Why is MLA Good? (Part 1)" and "Transformer Upgrade: 21. Why is MLA Good? (Part 2)". In short, we hope MLA can also have a mechanism similar to QK-Norm that guarantees the suppression of MaxLogit.

Direct Target

During our research, we also tried some indirect methods, such as separately reducing the learning rate for \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K} or increasing their Weight Decay, but none worked. The closest attempt to success was Partial QK-Norm. For MLA, its \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K} are divided into four parts: qr, qc, kr, and kc. The first three parts can be materialized during decoding, so we added RMSNorm to all three. The result was that MaxLogit was suppressed, but the performance on long-context activation was very poor.

After many failures, we began to reflect: our previous attempts were all "indirect means" of suppressing MaxLogit. What is the direct means that can guarantee solving MaxLogit explosion? From inequality [eq:kexi], it is easy to think of performing singular value clipping on \boldsymbol{W}_q and \boldsymbol{W}_k, but this is still essentially an indirect means, and the computational cost of singular value clipping is not low.

However, it is clear that post-scaling \boldsymbol{W}_q and \boldsymbol{W}_k is theoretically feasible. The question is when to scale and by how much. Finally, in a moment of inspiration, the author realized: MaxLogit itself is the most direct signal to trigger scaling! Specifically, when MaxLogit exceeds a desired threshold \tau, we directly multiply \boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{K}^{\top} by \gamma = \tau / S_{\max}, ensuring the new MaxLogit does not exceed \tau. This multiplication by \gamma can be absorbed into the weights of \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K} respectively. Thus, we obtain the first version of QK-Clip: \begin{equation*} \begin{aligned} &\boldsymbol{W}_t = \text{Optimizer}(\boldsymbol{W}_{t-1}, \boldsymbol{G}_t) \\ &\text{if }S_{\max}^{(l)} > \tau\text{ and }\boldsymbol{W} \in \{\boldsymbol{W}_q^{(l)}, \boldsymbol{W}_k^{(l)}\}: \\ &\qquad\boldsymbol{W}_t \leftarrow \boldsymbol{W}_t \times \sqrt{\tau / S_{\max}^{(l)}} \end{aligned} \end{equation*}

Where S_{\max}^{(l)} is the MaxLogit of the l-th Attention layer, and \boldsymbol{W}_q^{(l)}, \boldsymbol{W}_k^{(l)} are the weights for its \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K}. That is, after the optimizer update, we decide whether to clip the weights of \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K} based on the size of S_{\max}^{(l)}. The magnitude of clipping is directly determined by the ratio of S_{\max}^{(l)} to the threshold \tau, directly guaranteeing that the matrix after clipping no longer suffers from MaxLogit explosion. Furthermore, since this operation is performed directly on the weights, it does not affect inference mode and is naturally compatible with MLA.

Fine-tuning

The initial version of QK-Clip successfully suppressed MaxLogit in MLA, but after careful observation of the model’s "internal state," we found it suffered from "over-clipping." Fixing this issue led to the final version of QK-Clip.

We know that any Attention variant has multiple heads. Initially, we monitored only one MaxLogit per Attention layer, taking the maximum across all heads’ logits. This caused QK-Clip to clip all heads together. However, when we monitored the MaxLogit of each head separately, we found that only a few heads per layer actually experienced MaxLogit explosion. If all heads are clipped by the same ratio, most heads are "innocently affected." This is what over-clipping means.

Simply put, QK-Clip multiplies by a factor less than 1. For heads with MaxLogit explosion, this factor just offsets the growth trend, but for other heads, it is a pure reduction (as they have no or weak growth trends). Being repeatedly multiplied by a factor less than 1 over time can easily cause them to trend toward zero.

Therefore, to avoid "collateral damage," we should monitor MaxLogit and apply QK-Clip on a per-head basis. However, there is another hidden detail: the initial QK-Clip distributed the clipping factor equally between \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K}. But in MLA, \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K} consist of qr, qc, kr, and kc parts, where kr is shared across all heads. If we clip kr, we again face the problem of "collateral damage." Therefore, for (qr, kr), we should only apply the clip to qr.

After these adjustments, the final version of QK-Clip is: \begin{equation*} \begin{aligned} &\boldsymbol{W}_t = \text{Optimizer}(\boldsymbol{W}_{t-1}, \boldsymbol{G}_t) \\ &\text{if }S_{\max}^{(l,h)} > \tau: \\ &\qquad\text{if }\boldsymbol{W} \in \{\boldsymbol{W}_{qc}^{(l,h)}, \boldsymbol{W}_{kc}^{(l,h)}\}: \\ &\qquad\qquad\boldsymbol{W}_t \leftarrow \boldsymbol{W}_t \times \sqrt{\tau / S_{\max}^{(l,h)}} \\ &\qquad\text{elif }\boldsymbol{W} \in \{\boldsymbol{W}_{qr}^{(l,h)}\}: \\ &\qquad\qquad\boldsymbol{W}_t \leftarrow \boldsymbol{W}_t \times \tau / S_{\max}^{(l,h)} \end{aligned} \end{equation*} where the superscript {}^{(l,h)} denotes the h-th head of the l-th layer.

The Road to Scaling Up

At this point, the operational details of QK-Clip have been fully introduced. It uses our desired MaxLogit as a signal to make the smallest possible changes to the weights of \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K}, achieving the effect of controlling the MaxLogit value within a specified threshold. Because it is a method of directly modifying weights, it has better compatibility than QK-Norm and can be used for MLA.

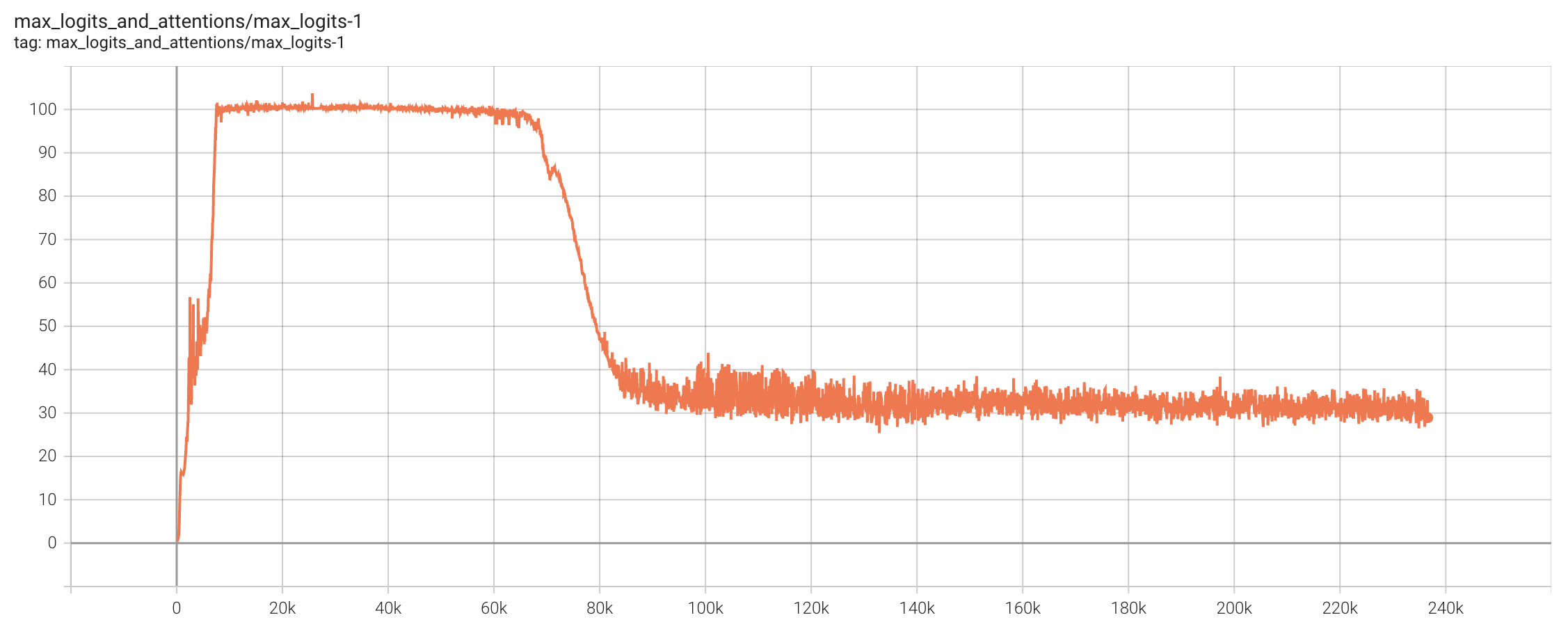

In the training of Kimi K2, we set the threshold \tau to 100, with a total training duration of approximately 220k steps. Starting from roughly 7k steps, heads with MaxLogit exceeding \tau began to appear. For a long time thereafter, Muon Update and QK-Clip were in a "tug-of-war"—Muon trying to increase MaxLogit and QK-Clip trying to decrease it, maintaining a delicate balance. Interestingly, after 70k steps, the MaxLogit of all heads spontaneously dropped below 100, and QK-Clip was no longer triggered.

This indicates that under the influence of Weight Decay, as long as we can stabilize training, the model is likely to eventually lower MaxLogit on its own. The role of QK-Clip is precisely to help the model pass through the early stages of training more smoothly. Some readers might worry that QK-Clip harms performance, but we conducted comparative experiments on small models. Even when MaxLogit was pressed very low (e.g., 30) via QK-Clip, no substantial difference in performance was observed. Combined with the phenomenon of MaxLogit spontaneously decreasing in the middle and late stages, we have reason to believe QK-Clip is lossless for performance.

We also observed in experiments that Muon is generally more prone to MaxLogit explosion than Adam. So, in a sense, QK-Clip is a supplementary update rule specifically for Muon, one of the "secrets to success" for Muon in ultra-large-scale training. For this reason, we combined the Muon modifications proposed in Moonlight with QK-Clip and named it "MuonClip" (\boldsymbol{W}\in\mathbb{R}^{n\times m}): \begin{equation*} \text{MuonClip}\quad\left\{\quad\begin{aligned} &\boldsymbol{M}_t = \mu \boldsymbol{M}_{t-1} + \boldsymbol{G}_t \\[8pt] &\boldsymbol{O}_t = \mathop{\mathrm{msign}}(\boldsymbol{M}_t) \underbrace{\times \sqrt{\max(n,m)}\times 0.2}_{\text{Match Adam Update RMS}} \\[8pt] &\boldsymbol{W}_t = \boldsymbol{W}_{t-1} - \eta_t (\boldsymbol{O}_t + \lambda \boldsymbol{W}_{t-1}) \\[8pt] &\left.\begin{aligned} &\text{if }S_{\max}^{(l,h)} > \tau: \\ &\qquad\text{if }\boldsymbol{W} \in \{\boldsymbol{W}_{qc}^{(l,h)}, \boldsymbol{W}_{kc}^{(l,h)}\}: \\ &\qquad\qquad\boldsymbol{W}_t \leftarrow \boldsymbol{W}_t \times \sqrt{\tau / S_{\max}^{(l,h)}} \\ &\qquad\text{elif }\boldsymbol{W} \in \{\boldsymbol{W}_{qr}^{(l,h)}\}: \\ &\qquad\qquad\boldsymbol{W}_t \leftarrow \boldsymbol{W}_t \times \tau / S_{\max}^{(l,h)} \end{aligned}\quad\right\} \text{QK-Clip} \end{aligned}\right. \end{equation*}

Note that "Muon is generally more prone to MaxLogit explosion" does not mean only Muon explodes. We know that DeepSeek-V3 was trained with Adam, and we observed MaxLogit explosion in the open-source DeepSeek-V3 model. Gemma 2 also used \text{softcap} to prevent MaxLogit explosion while being trained with Adam. Therefore, while we emphasize the value of QK-Clip for Muon, if readers insist on using Adam, it can also be combined with Adam to form "AdamClip."

Reflections on the Cause

Why is Muon more likely to cause MaxLogit explosion? In this section, the author attempts to provide a theoretical explanation for reference.

From inequality [eq:kexi], it can be seen that MaxLogit explosion often implies that the spectral norm of \boldsymbol{W}_q or \boldsymbol{W}_k shows signs of exploding. In fact, the definition of the spectral norm also involves a \max operation; the two are essentially connected. Therefore, the question can be transformed into "why is Muon more likely to cause spectral norm explosion." We know the spectral norm equals the largest singular value, so we can further associate this with "why Muon tends to increase singular values."

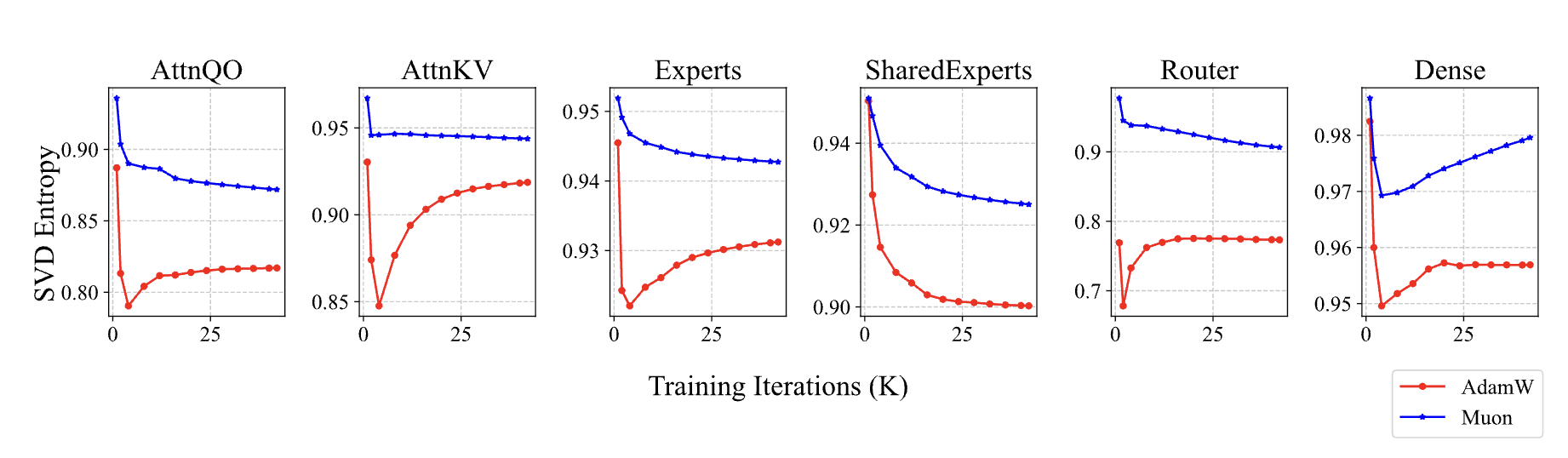

What is the difference between Muon and Adam? The update amount provided by Muon undergoes an \mathop{\mathrm{msign}} operation, meaning all singular values are equal, and its effective rank is full rank. In contrast, for a typical matrix, singular values vary in size and are dominated by the first few; from the perspective of effective rank, they are low rank. This is also our assumption for Adam’s update amount. This assumption is not new; for example, High-order MuP similarly assumes the low-rank nature of Adam updates.

Using formulas, let the SVD of the parameter \boldsymbol{W}_{t-1} be \sum_i \sigma_i \boldsymbol{u}_i \boldsymbol{v}_i^{\top}, the SVD of the Muon update be \sum_j \bar{\sigma}\bar{\boldsymbol{u}}_j \bar{\boldsymbol{v}}_j^{\top}, and the SVD of the Adam update be \sum_j \tilde{\sigma}_j\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}_j \tilde{\boldsymbol{v}}_j^{\top}. Then: \begin{gather} \boldsymbol{W}_t = \sum_i \sigma_i \boldsymbol{u}_i \boldsymbol{v}_i^{\top} + \sum_j \bar{\sigma}\bar{\boldsymbol{u}}_j \bar{\boldsymbol{v}}_j^{\top}\qquad (\text{Muon}) \\ \boldsymbol{W}_t = \sum_i \sigma_i \boldsymbol{u}_i \boldsymbol{v}_i^{\top} + \sum_j \tilde{\sigma}_j\tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}_j \tilde{\boldsymbol{v}}_j^{\top}\qquad (\text{Adam}) \end{gather}

Clearly, if a singular vector pair \boldsymbol{u}_i \boldsymbol{v}_i^{\top} is very close to some \bar{\boldsymbol{u}}_j \bar{\boldsymbol{v}}_j^{\top} or \tilde{\boldsymbol{u}}_j \tilde{\boldsymbol{v}}_j^{\top}, they will directly superimpose, thereby increasing the singular values of \boldsymbol{W}_t. Since Muon’s update is full rank, its "collision probability" with \boldsymbol{W}_{t-1} is much higher than Adam’s, making Muon more likely to increase the singular values of the parameters.

Of course, the above analysis is general and not limited to the weights of \boldsymbol{Q} and \boldsymbol{K}. In Moonlight, we already verified that the singular value entropy of model weights trained with Muon is generally higher, supporting this hypothesis. The special thing about Attention Logit is its bilinear form \boldsymbol{q}_i\cdot \boldsymbol{k}_j = (\boldsymbol{x}_i \boldsymbol{W}_q)\cdot(\boldsymbol{x}_j \boldsymbol{W}_k). The multiplication of \boldsymbol{W}_q and \boldsymbol{W}_k makes the risk of explosion greater and easily leads to a vicious cycle of "the bad getting worse," ultimately resulting in MaxLogit explosion.

Finally, the "collision probability of Muon being much higher than Adam" is relative. In reality, singular vector collisions are still rare events, which explains why only a small portion of Attention Heads experience MaxLogit explosion.

This perspective also explains a phenomenon from Moonlight: models pre-trained with Muon/Adam and then fine-tuned with Adam/Muon usually yield suboptimal results. Because Muon’s weights have higher effective rank while Adam’s updates are low-rank, the fine-tuning efficiency suffers. Conversely, Adam’s weights have lower effective rank, but Muon’s updates are full-rank, giving them a higher probability of interfering with small singular value components and pushing the model away from the low-rank local optimum of pre-training.

Extensions

By now, the important computational and experimental details of QK-Clip should be clear. It should also be noted that while the idea of QK-Clip is simple, implementing it in distributed training is somewhat challenging because it requires per-head clipping, and parameter matrices are often "fragmented" across devices. (Modifying it based on Muon is not too hard, but doing so for Adam is slightly more complex).

For the author and his team, QK-Clip is not just a specific method to solve the MaxLogit explosion problem, but also a "realization" after repeatedly failing with indirect means: Since we have a clear metric, we should seek a direct approach that guarantees a solution, rather than wasting time on ideas like lowering LR, increasing Weight Decay, or Partial QK-Norm, which might but do not necessarily solve the problem.

Methodologically, the idea of QK-Clip is not limited to solving MaxLogit explosion; it can be seen as an "antibiotic" for many training instability problems. By "antibiotic," I mean it might not be the most elegant method, but it is often one of the most direct and effective. QK-Clip can be generalized to "clip wherever it is unstable."

For example, in some cases, models encounter "MaxOutput explosion." In such instances, we could consider clipping the weight \boldsymbol{W}_o based on the MaxOutput value. Analogous to the per-head operation in QK-Clip, we would need to consider per-dimension operations here, though the cost of per-dimension clipping might be too high, requiring a compromise. In short, "clip wherever it is unstable" provides a unified problem-solving framework, but the specific details depend on individual implementation.

Finally, the operation of manually formulating update rules based on certain signals in QK-Clip was partly inspired by DeepSeek’s Loss-Free load balancing strategy. Tribute to DeepSeek once again!

Summary

This article proposes QK-Clip, a new approach to the MaxLogit explosion problem. Unlike QK-Norm, it is a post-adjustment scheme for Q and K weights that does not change the model’s forward computation, making it more widely applicable. It is a vital stabilization strategy for the "Muon + MLA" combination in ultra-large-scale training and one of the key technologies for our newly released trillion-parameter model, Kimi K2.

When reposting, please include the original address: https://kexue.fm/archives/11126

For more details on reposting, please refer to: "Scientific Space FAQ"