Two days ago, a member of a QQ group posted an inequality to be proven:

The short problem statement, combined with the hint “easily,” makes it seem like an obvious result. However, the person who asked mentioned that they had tried for a long time without success. So, what is the actual situation? Is it truly obvious?

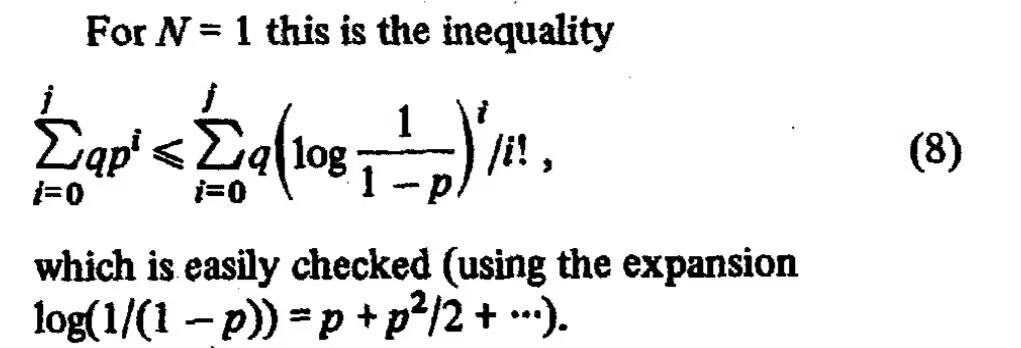

Preliminary Attempt

The problem is equivalent to proving: \begin{equation} \sum_{i=0}^j p^i \leq \sum_{i=0}^j \left(\log\frac{1}{1-p}\right)^i/i!,\qquad p\in[0, 1)\label{eq:q} \end{equation} The provided hint is: \begin{equation} \log\frac{1}{1-p} = \sum_{i=1}^{\infty} \frac{p^i}{i} = p + \frac{p^2}{2} + \frac{p^3}{3} + \cdots \label{eq:log-1-p} \end{equation} This hint seems to guide us to replace the \log\frac{1}{1-p} on the right side of Eq. [eq:q] and then expand it into a power series of p for a term-by-term comparison. Since all coefficients in the expansion of \log\frac{1}{1-p} are positive, the coefficients of each term in the power series expansion of Eq. [eq:q] must also be positive. Therefore, we only need to prove that the coefficients of the first j terms are greater than or equal to 1.

The logic seems sound, but re-expanding the i-th power of a power series into a new power series is a very tedious task, making it difficult to carry out in practice. I also tried other approaches, such as setting x=\log\frac{1}{1-p} to transform it into an inequality regarding x. This also looked promising, but ultimately I got stuck and could not complete the proof.

Thus, the first attempt was declared a failure.

Taylor Brute Force

After going in circles, I returned to the starting point. After trying for half a day, I still felt that the idea of expanding the right side of Eq. [eq:q] into a power series was the most reliable. But if directly raising Eq. [eq:log-1-p] to a power doesn’t work, we must return to the original method of Taylor expansion—differentiation.

For simplicity, we define: \begin{equation} f_j(x) = \sum_{i=0}^j \frac{x^i}{i!} \end{equation} The original problem is to prove: \begin{equation} f_j(x) \geq \sum_{i=0}^j p^i,\qquad x = \log\frac{1}{1-p} \end{equation} We transform this into proving: \begin{equation} \left.\frac{d^k}{dp^k}f_j(x)\right|_{p=0} \,\,\geq\,\, \left\{\begin{aligned}&\, 1,\,\, k \leq j \\[5pt] &\,0,\,\, k > j\end{aligned}\right. \end{equation} Note that when j \geq 0, f_j(0)=1; when j < 0, we define f_j(x)\equiv 0. Also, f_j'(x)= f_{j-1}(x) holds. Thus, we have: \begin{gather} \frac{d}{dp}f_j(x) = f_{j-1}(x) \frac{1}{1-p} \\ \frac{d^2}{dp^2}f_j(x) = [f_{j-1}(x) + f_{j-2}(x)]\frac{1}{(1-p)^2} \\ \frac{d^3}{dp^3}f_j(x) = [2f_{j-1}(x) + 3f_{j-2}(x) + f_{j-3}(x)]\frac{1}{(1-p)^3} \\ \vdots \notag\\ \frac{d^k}{dp^k}f_j(x) = [\alpha_1 f_{j-1}(x) + \alpha_2 f_{j-2}(x) + \cdots + \alpha_k f_{j-k}(x)]\frac{1}{(1-p)^k} \\[8pt] \frac{d^{k+1}}{dp^{k+1}}f_j(x) = \left[\begin{aligned} \alpha_1 f_{j-2}(x) + \alpha_2 f_{j-3}(x) + \cdots + \alpha_k f_{j-k-1}(x) \\ + k(\alpha_1 f_{j-1}(x) + \alpha_2 f_{j-2}(x) + \cdots + \alpha_k f_{j-k}(x)) \end{aligned}\right]\frac{1}{(1-p)^{k+1}} \end{gather} The pattern: \frac{d^k}{dp^k}f_j(x) is a product of a linear combination of f_{j-1}(x), f_{j-2}(x), \dots, f_{j-k}(x) and \frac{1}{(1-p)^k}. Note that we only care about the value of \left.\frac{d^k}{dp^k}f_j(x)\right|_{p=0}. Substituting p=0 into the above expression makes it equal to the sum of the coefficients of the non-zero terms in f_{j-1}(x), f_{j-2}(x), \dots, f_{j-k}(x) (note that f_{j-1}(0), f_{j-2}(0), \dots, f_{j-k}(0) are either 1 or 0). According to the differentiation rule of f_j(x), we can conclude: when k \leq j, we have: \begin{equation} \left.\frac{d^k}{dp^k}f_j(x)\right|_{p=0} = k \times \left.\frac{d^{k-1}}{dp^{k-1}}f_j(x)\right|_{p=0} \end{equation} Therefore, \left.\frac{d^k}{dp^k}f_j(x)\right|_{p=0} = k!. Thus, according to the Taylor expansion, the coefficient of the p^k term is k!/k!=1. When k > j, since f_{j-k}(0)=0 at this point, \left.\frac{d^k}{dp^k}f_j(x)\right|_{p=0} < k!, so the coefficient of the p^k term is less than 1, but still greater than zero. Therefore, the inequality to be proven holds.

Obvious and Easy

It seems the original problem wasn’t as “obvious” as the author claimed? I thought so too, until another group member provided an extremely simple perspective. I suddenly realized that this problem really is obviously true!

This perspective fully demonstrates reverse thinking, as follows: \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \sum_{i=0}^j \left(\log\frac{1}{1-p}\right)^i/i! =&\, \sum_{i=0}^{\infty} \left(\log\frac{1}{1-p}\right)^i/i! - \sum_{i=j+1}^{\infty} \left(\log\frac{1}{1-p}\right)^i/i! \\ =&\, \exp\left(\log\frac{1}{1-p}\right) - \sum_{i=j+1}^{\infty} \left(\log\frac{1}{1-p}\right)^i/i! \\ =&\, \frac{1}{1-p} - \sum_{i=j+1}^{\infty} \left(\log\frac{1}{1-p}\right)^i/i! \\ =&\, \sum_{i=0}^{\infty} p^i - \sum_{i=j+1}^{\infty} \left(\log\frac{1}{1-p}\right)^i/i! \\ \end{aligned} \end{equation} Note that \log\frac{1}{1-p} \sim p, so the trailing \sum_{i=j+1}^{\infty} part only contributes to terms of p^{j+1} and higher. Therefore, we have almost obviously proven that the coefficients of the first j+1 terms in the right-hand expansion are all 1! The entire proof is not hard to understand; the truly difficult part is having the courage to push the summation on the right to infinity and then noticing that the error term only contributes to p^{j+1} and above. This is classic reverse thinking.

Mathematics is truly wonderful…