In this post, I will interpret our latest technical report, "Muon is Scalable for LLM Training". It shares a large-scale practice of the Muon optimizer, which we previously introduced in "Muon Optimizer Appreciation: An Essential Leap from Vectors to Matrices". We have also open-sourced the corresponding models (which we call "Moonlight", currently a 3B/16B MoE model). We discovered a rather striking conclusion: under our experimental setup, Muon can achieve nearly double the training efficiency compared to Adam.

Work on optimizers can be seen as either plenty or scarce, but why did we choose Muon as a new direction to explore? How can one quickly switch from an Adam optimizer with well-tuned hyperparameters to Muon? How does the performance difference between Muon and Adam evolve as the model scales up? In the following, I will share our thought process.

Optimization Principles

Regarding optimizers, I previously offered a brief critique in "Muon Optimizer Appreciation". Most optimizer improvements are actually just small patches; they aren’t valueless, but they ultimately fail to give a profound or stunning impression.

We need to start from principles closer to the essence to think about what constitutes a good optimizer. Intuitively, an ideal optimizer should have two characteristics: stability and speed. Specifically, the update at each step should satisfy two points: 1. Minimal perturbation to the model; 2. Maximal contribution to the Loss reduction. To put it more bluntly, we don’t want to change the model drastically (stability), but we want to drop the Loss significantly (speed)—a classic case of "wanting to have one’s cake and eat it too."

How can we translate these two characteristics into mathematical language? Stability can be understood as a constraint on the update amount, while speed can be understood as finding the update amount that makes the loss function decrease fastest. Thus, this can be transformed into a constrained optimization problem. Using the notation from the previous article, for a matrix parameter \boldsymbol{W}\in\mathbb{R}^{n\times m} with gradient \boldsymbol{G}\in\mathbb{R}^{n\times m}, when the parameter changes from \boldsymbol{W} to \boldsymbol{W}+\Delta\boldsymbol{W}, the change in the loss function is: \begin{equation} \text{Tr}(\boldsymbol{G}^{\top}\Delta\boldsymbol{W}) \end{equation} Then, finding the fastest update amount under the premise of stability can be expressed as: \begin{equation} \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{\Delta\boldsymbol{W}}\text{Tr}(\boldsymbol{G}^{\top}\Delta\boldsymbol{W})\quad\text{s.t.}\quad \rho(\Delta\boldsymbol{W})\leq \eta \label{eq:least-action} \end{equation} Here \rho(\Delta\boldsymbol{W})\geq 0 is a certain metric for stability (smaller means more stable), and \eta is a constant less than 1, representing our requirement for stability; we will see later that it is actually the optimizer’s learning rate. If readers don’t mind, we can borrow a concept from theoretical physics and call the above principle the optimizer’s "Least Action Principle".

Matrix Norms

The only uncertainty in Equation [eq:least-action] is the stability metric \rho(\Delta\boldsymbol{W}). Once \rho(\Delta\boldsymbol{W}) is selected, \Delta\boldsymbol{W} can be explicitly solved (at least in theory). To some extent, we can consider the essential difference between different optimizers to be their different definitions of stability.

Many readers likely encountered the statement that "the negative gradient direction is the direction of fastest local descent" when first learning SGD. Within this framework, it actually chooses the Frobenius norm \|\Delta\boldsymbol{W}\|_F as the metric for stability. In other words, the "direction of fastest descent" is not immutable; it is only determined after a metric is chosen. If you change the norm, it might not be the negative gradient direction anymore.

The next question is naturally: which norm most appropriately measures stability? If we add a constraint that is too strong, it will be stable, but the optimizer will struggle and only converge to a sub-optimal solution. Conversely, if we weaken the constraint and let the optimizer run wild, the training process will become extremely uncontrollable. Therefore, the ideal situation is to find the most accurate indicator of stability. Considering that neural networks are dominated by matrix multiplications, let’s take \boldsymbol{y}=\boldsymbol{x}\boldsymbol{W} as an example: \begin{equation} \|\Delta \boldsymbol{y}\| = \|\boldsymbol{x}(\boldsymbol{W} + \Delta\boldsymbol{W}) - \boldsymbol{x}\boldsymbol{W}\| = \|\boldsymbol{x} \Delta\boldsymbol{W}\|\leq \rho(\Delta\boldsymbol{W}) \|\boldsymbol{x}\| \end{equation} The meaning of the above equation is that when the parameter changes from \boldsymbol{W} to \boldsymbol{W}+\Delta\boldsymbol{W}, the change in model output is \Delta\boldsymbol{y}. We hope the magnitude of this change can be controlled by \|\boldsymbol{x}\| and a function \rho(\Delta\boldsymbol{W}) related to \Delta\boldsymbol{W}. We use this function as the indicator of stability. From linear algebra, we know that the most accurate value for \rho(\Delta\boldsymbol{W}) is the spectral norm \|\Delta\boldsymbol{W}\|_2. Substituting this into Equation [eq:least-action], we get: \begin{equation} \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{\Delta\boldsymbol{W}}\text{Tr}(\boldsymbol{G}^{\top}\Delta\boldsymbol{W})\quad\text{s.t.}\quad \|\Delta\boldsymbol{W}\|_2\leq \eta \end{equation} Solving this optimization problem yields Muon with \beta=0: \begin{equation} \Delta\boldsymbol{W} = -\eta\, \text{msign}(\boldsymbol{G}) = -\eta\,\boldsymbol{U}_{[:,:r]}\boldsymbol{V}_{[:,:r]}^{\top}, \quad \boldsymbol{U},\boldsymbol{\Sigma},\boldsymbol{V}^{\top} = \mathop{\text{SVD}}(\boldsymbol{G}) \end{equation} When \beta > 0, \boldsymbol{G} is replaced by the momentum \boldsymbol{M}. Since \boldsymbol{M} can be seen as a smoother estimate of the gradient, the conclusion of the above equation still holds. Therefore, we can conclude that "Muon is the steepest descent under the spectral norm." As for the Newton-Schulz iteration, it is a computational approximation, which I won’t detail here. The detailed derivation was already given in "Muon Optimizer Appreciation" and will not be repeated.

Weight Decay

At this point, we can answer the first question: why choose to try Muon? Because like SGD, Muon provides the direction of fastest descent, but its spectral norm constraint is more accurate than SGD’s F-norm, so it has better potential. On the other hand, improving the optimizer from the perspective of "choosing the most appropriate constraint for different parameters" also seems more fundamental than various patch-style modifications.

Of course, potential does not mean immediate strength. Validating Muon on larger models involves some "traps." First is the Weight Decay issue. Although we included Weight Decay when introducing Muon in "Muon Optimizer Appreciation", it was actually absent when the author first proposed Muon. We initially followed the official version, and the result was that Muon converged faster in the early stages but was soon caught by Adam, and various "internal dynamics" showed signs of collapse.

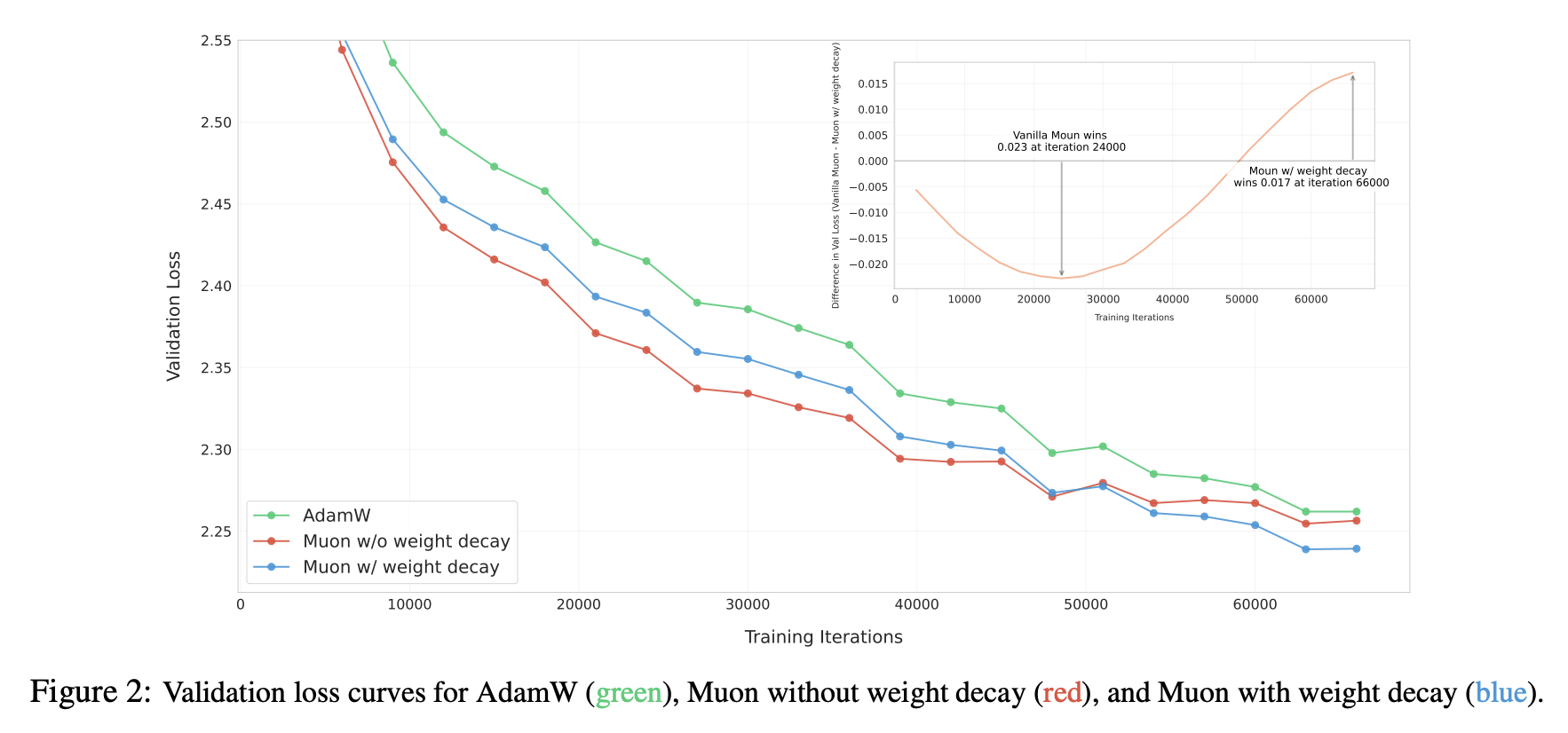

We quickly realized this might be a Weight Decay issue, so we added it: \begin{equation} \Delta\boldsymbol{W} = -\eta\, [\text{msign}(\boldsymbol{M})+ \lambda \boldsymbol{W}] \end{equation} Continuing the experiment, as expected, Muon then maintained a lead over Adam, as shown in Figure 2 of the paper:

What role does Weight Decay play? From a post-hoc analysis, a key factor might be its ability to keep the parameter norm bounded: \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \|\boldsymbol{W}_t\| =&\, \|\boldsymbol{W}_{t-1} - \eta_t (\boldsymbol{\Phi}_t + \lambda \boldsymbol{W}_{t-1})\| \\[5pt] =&\, \|(1 - \eta_t \lambda)\boldsymbol{W}_{t-1} - \eta_t \lambda (\boldsymbol{\Phi}_t/\lambda)\| \\[5pt] \leq &\,(1 - \eta_t \lambda)\|\boldsymbol{W}_{t-1}\| + \eta_t \lambda \|\boldsymbol{\Phi}_t/\lambda\| \\[5pt] \leq &\,\max(\|\boldsymbol{W}_{t-1}\|,\|\boldsymbol{\Phi}_t/\lambda\|) \\[5pt] \end{aligned} \end{equation} Here \|\cdot\| is any matrix norm; the above inequality holds for any matrix norm. \boldsymbol{\Phi}_t is the update vector provided by the optimizer, which for Muon is \text{msign}(\boldsymbol{M}). When we take the spectral norm, we have \|\text{msign}(\boldsymbol{M})\|_2 = 1, so for Muon: \begin{equation} \|\boldsymbol{W}_t\|_2 \leq \max(\|\boldsymbol{W}_{t-1}\|_2,1/\lambda)\leq\cdots \leq \max(\|\boldsymbol{W}_0\|_2,1/\lambda) \end{equation} This ensures the "internal health" of the model. Since \|\boldsymbol{x}\boldsymbol{W}\|\leq \|\boldsymbol{x}\|\|\boldsymbol{W}\|_2, controlling \|\boldsymbol{W}\|_2 means \|\boldsymbol{x}\boldsymbol{W}\| is also controlled, eliminating the risk of explosion. This is particularly important for issues like Attention Logits explosion. Of course, this upper bound is quite loose in most cases; in practice, the spectral norm of parameters is usually significantly smaller than this bound. This inequality simply demonstrates that Weight Decay has the property of controlling the norm.

RMS Alignment

When we decide to try a new optimizer, a headache is how to quickly find hyperparameters close to optimal, such as Muon’s learning rate \eta_t and decay rate \lambda. Grid search is possible but time-consuming. Here, we propose a hyperparameter transfer idea based on Update RMS Alignment, which allows using hyperparameters tuned for Adam on other optimizers.

First, for a matrix \boldsymbol{W}\in\mathbb{R}^{n\times m}, its RMS (Root Mean Square) is defined as: \begin{equation} \text{RMS}(\boldsymbol{W}) = \frac{\|\boldsymbol{W}\|_F}{\sqrt{nm}} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{nm}\sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^m W_{i,j}^2} \end{equation} Simply put, RMS measures the average size of each element in the matrix. We observed that the RMS of Adam’s update amount is relatively stable, usually between 0.2 and 0.4. This is why theoretical analysis often uses SignSGD as an approximation for Adam. Based on this, we suggest aligning the Update RMS of the new optimizer to 0.2 via RMS Norm: \begin{gather} \boldsymbol{W}_t =\boldsymbol{W}_{t-1} - \eta_t (\boldsymbol{\Phi}_t + \lambda \boldsymbol{W}_{t-1}) \\[6pt] \downarrow \notag\\[6pt] \boldsymbol{W}_t = \boldsymbol{W}_{t-1} - \eta_t (0.2\, \boldsymbol{\Phi}_t/\text{RMS}(\boldsymbol{\Phi}_t) + \lambda \boldsymbol{W}_{t-1}) \end{gather} In this way, we can reuse Adam’s \eta_t and \lambda to achieve the effect of having roughly the same update magnitude for parameters at each step. Practice shows that by using this simple strategy to migrate from Adam to Muon, one can train effects significantly better than Adam, approaching the results of further fine-searching Muon’s hyperparameters. Specifically, Muon’s \text{RMS}(\boldsymbol{\Phi}_t)=\text{RMS}(\boldsymbol{U}_{[:,:r]}\boldsymbol{V}_{[:,:r]}^{\top}) can even be calculated analytically: \begin{equation} nm\,\text{RMS}(\boldsymbol{\Phi}_t)^2 = \sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^m \sum_{k=1}^r U_{i,k}^2V_{k,j}^2 = \sum_{k=1}^r\left(\sum_{i=1}^n U_{i,k}^2\right)\left(\sum_{j=1}^m V_{k,j}^2\right) = \sum_{k=1}^r 1 = r \end{equation} That is, \text{RMS}(\boldsymbol{\Phi}_t) = \sqrt{r/nm}. In practice, the probability of a matrix being strictly low-rank is small, so we can assume r = \min(n,m), leading to \text{RMS}(\boldsymbol{\Phi}_t) = \sqrt{1/\max(n,m)}. Therefore, we ultimately did not use RMS Norm but used the equivalent analytical version: \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{W}_t = \boldsymbol{W}_{t-1} - \eta_t (0.2\, \boldsymbol{\Phi}_t\,\sqrt{\max(n,m)} + \lambda \boldsymbol{W}_{t-1}) \end{equation} This final formula indicates that in Muon, it is not appropriate to use the same learning rate for all parameters. For example, Moonlight is an MoE model, and many matrix parameter shapes deviate from square matrices; the span of \max(n,m) is quite large. If a single learning rate is used, it will inevitably lead to synchronization issues where some parameters learn too fast or too slow, affecting the final result.

Experimental Analysis

We conducted a thorough comparison between Adam and Muon on a 2.4B/16B MoE model and found that Muon has a clear advantage in both convergence speed and final performance. For detailed comparison results, I recommend reading the original paper; here I will only share some excerpts.

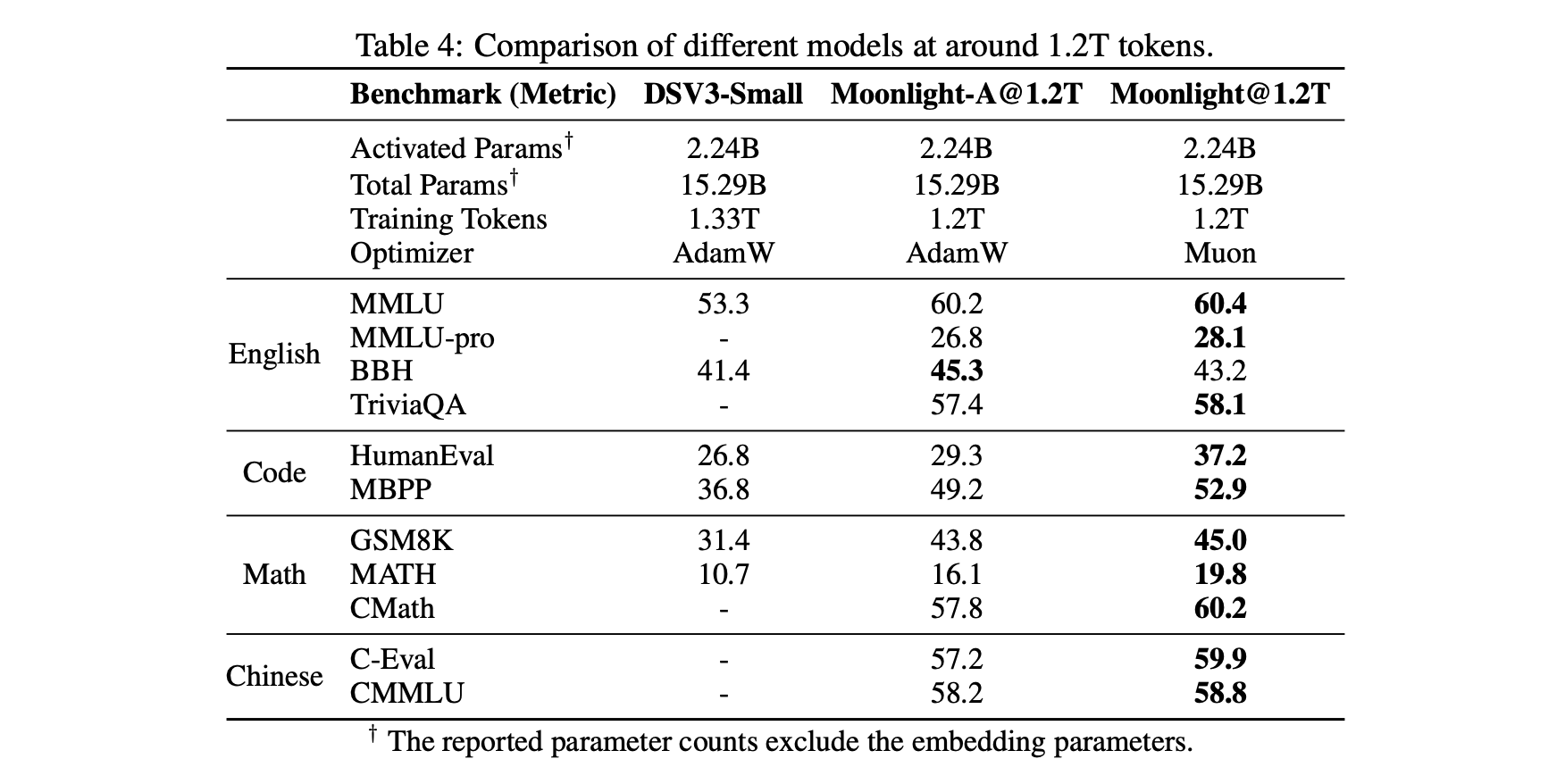

First is a relatively objective comparison table, including the comparison between Muon and Adam trained by ourselves with controlled variables, as well as a comparison with models of the same architecture trained by external parties (DeepSeek) using Adam (for ease of comparison, Moonlight’s architecture is identical to DSV3-Small). This shows Muon’s unique advantage:

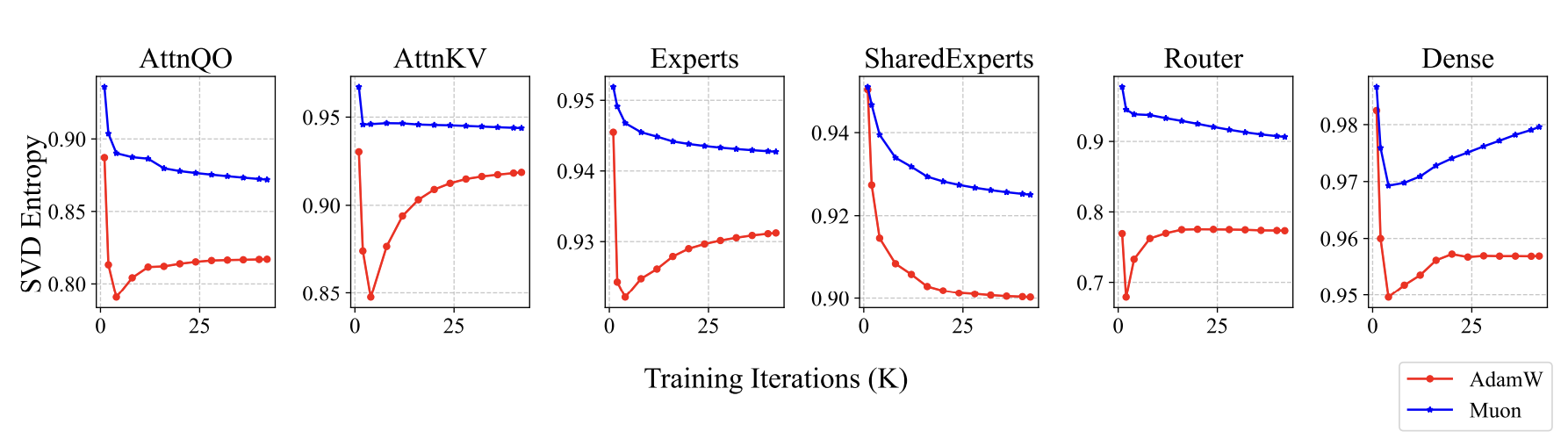

What is different about the models trained with Muon? Since we said Muon is the steepest descent under the spectral norm (the largest singular value), we thought of monitoring and analyzing singular values. Sure enough, we found some interesting signals. The parameters trained by Muon have a relatively more uniform singular value distribution. We use singular value entropy to quantitatively describe this phenomenon: \begin{equation} H(\boldsymbol{\sigma}) = -\frac{1}{\log n}\sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\sigma_i^2}{\sum_{j=1}^n\sigma_j^2}\log \frac{\sigma_i^2}{\sum_{j=1}^n\sigma_j^2} \end{equation} Here \boldsymbol{\sigma}=(\sigma_1,\sigma_2,\cdots,\sigma_n) are all the singular values of a parameter. Parameters trained by Muon have higher entropy, meaning the singular value distribution is more uniform, which implies the parameters are less compressible. This suggests that Muon more fully utilizes the potential of the parameters:

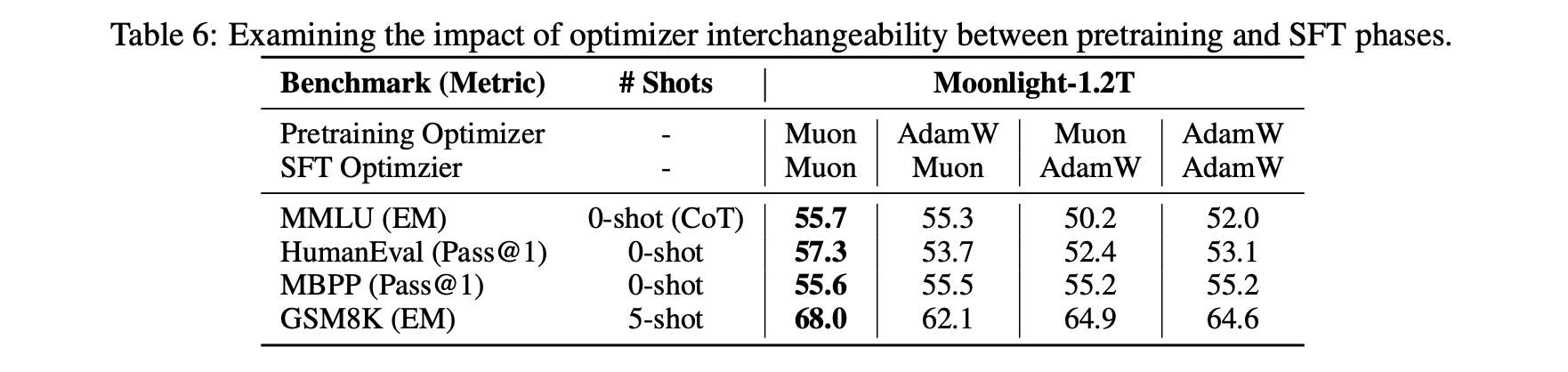

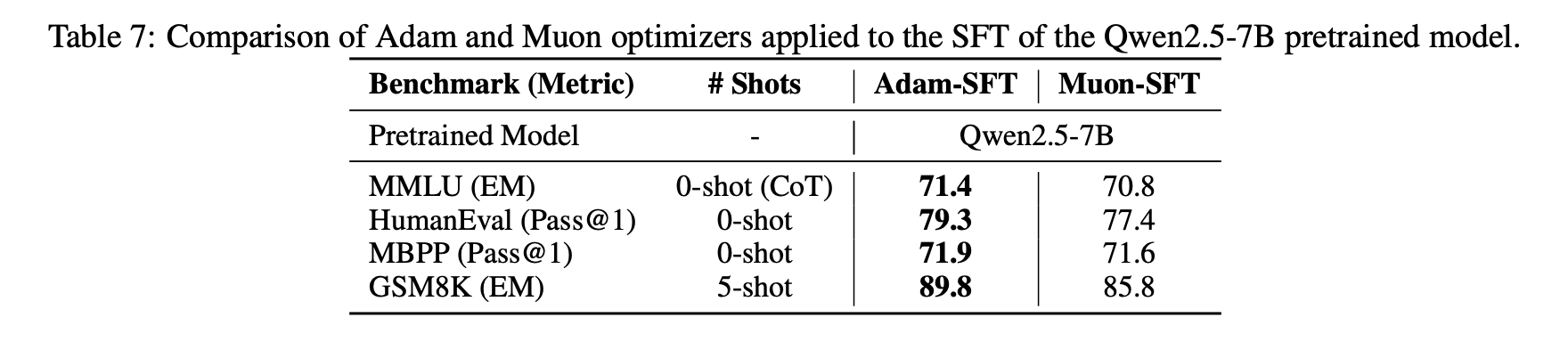

Another interesting discovery is that when we use Muon for fine-tuning (SFT), we might get a sub-optimal solution because Muon was not used during pre-training. Specifically, if both pre-training and fine-tuning use Muon, the performance is best. However, for the other three combinations (Adam+Muon, Muon+Adam, Adam+Adam), the performance superiority does not show a clear pattern.

This phenomenon suggests that certain special initializations are unfavorable for Muon. Conversely, some initializations might be more favorable for Muon. We are still exploring the underlying principles.

Extended Thinking

Overall, in our experiments, Muon’s performance is very competitive compared to Adam. As a new optimizer that differs significantly in form from Adam, Muon’s performance is not just "noteworthy"; it indicates that it might have captured some essential characteristics.

Previously, a view circulated in the community: Adam performs well because mainstream model architecture improvements are "overfitting" Adam. This view likely originated from "Neural Networks (Maybe) Evolved to Make Adam The Best Optimizer". It sounds a bit absurd, but it is actually quite profound. Imagine that when we try to improve a model, we train it with Adam to see the effect. If the effect is good, we keep it; otherwise, we discard it. But is this "good effect" because it is inherently better, or because it is a better match for Adam?

This is quite intriguing. Certainly, at least some work is successful because it matches Adam better. Over time, model architectures evolve in a direction favorable to Adam. In this context, it is particularly worth noting and reflecting on when an optimizer significantly different from Adam can still "break out." Note that neither I nor my company are the proposers of Muon, so these remarks are purely "from the heart" and not self-promotion.

What work remains for Muon? Actually, quite a lot. For example, the "Adam pre-training + Muon fine-tuning" issue mentioned above deserves further analysis. After all, most open-source model weights are currently trained with Adam. If Muon fine-tuning doesn’t work well, it will inevitably affect its adoption. Of course, we can also use this opportunity to further deepen our understanding of Muon (learning through bugs).

Another generalized thought is that Muon is based on the spectral norm, which is the largest singular value. In fact, we can construct a series of norms based on singular values, such as Schatten norms. Generalizing Muon to these broader norms and tuning them might theoretically yield even better results. Additionally, after the release of Moonlight, some readers asked how to design \muP (maximal update parametrization) under Muon, which is also an urgent problem to solve.

Summary

This article introduced our large-scale practice with the Muon optimizer (Moonlight) and shared our latest reflections on the Muon optimizer.

When reposting, please include the original address: https://kexue.fm/archives/10739

For more detailed reposting matters, please refer to: "Scientific Space FAQ"