I wonder if any readers still remember this series? This series, titled "Flowing with the Flow", primarily introduces work related to flow models. It originated back in 2018 when OpenAI released a new flow model, Glow, which was truly stunning at a time when GANs were the mainstream. However, despite the initial amazement, for a long time, Glow and its subsequent improvements could not match GANs in terms of generation quality, let alone the currently dominant diffusion models.

But the situation might be about to change. Last month, the paper "Normalizing Flows are Capable Generative Models" proposed a new flow model called TARFLOW. It approaches current SOTA performance in almost all generation tasks, marking a "full strength" return for flow models.

Introduction

The "flow models" here specifically refer to Normalizing Flows—work characterized by reversible model architectures, trained with maximum likelihood, and capable of one-step generation. Flow Matching, a branch of current diffusion models, is not included in this category.

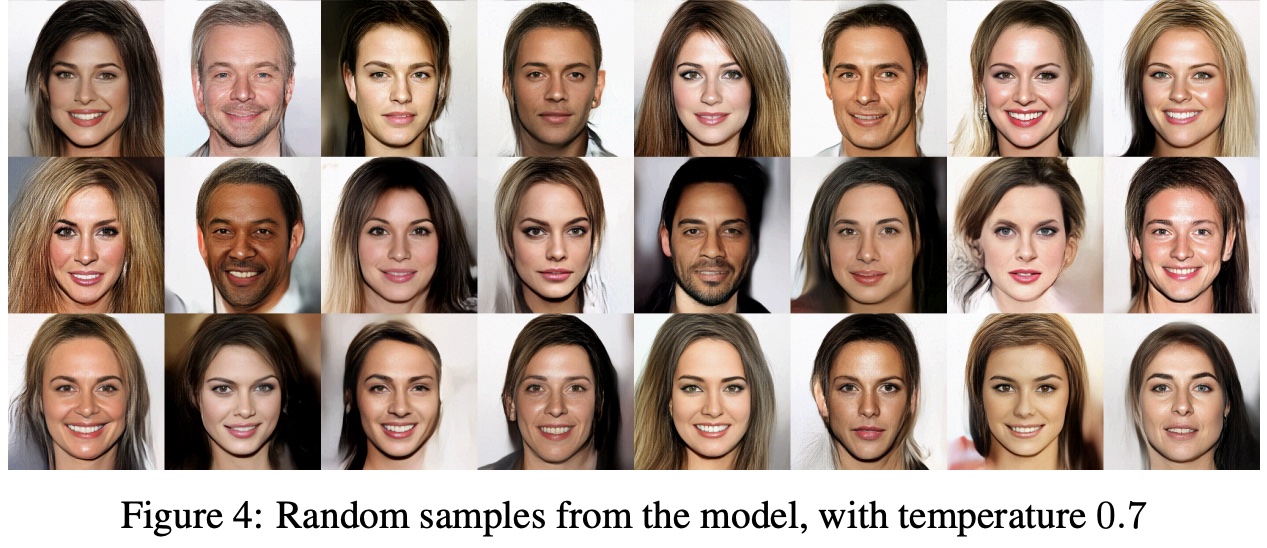

Since the brilliant debut of Glow, subsequent progress in flow models has been somewhat "unremarkable." Simply put, it was difficult for them to generate CelebA faces without obvious artifacts, let alone the more complex ImageNet. Consequently, the "Flowing with the Flow" series stopped in 2019 with "Flowing with the Flow: Reversible ResNet - The Ultimate Brutalist Aesthetic". However, the emergence of TARFLOW proves that flow models are "still in the game." This time, its generation style looks like this:

In contrast, the generation style of the previous Glow was like this:

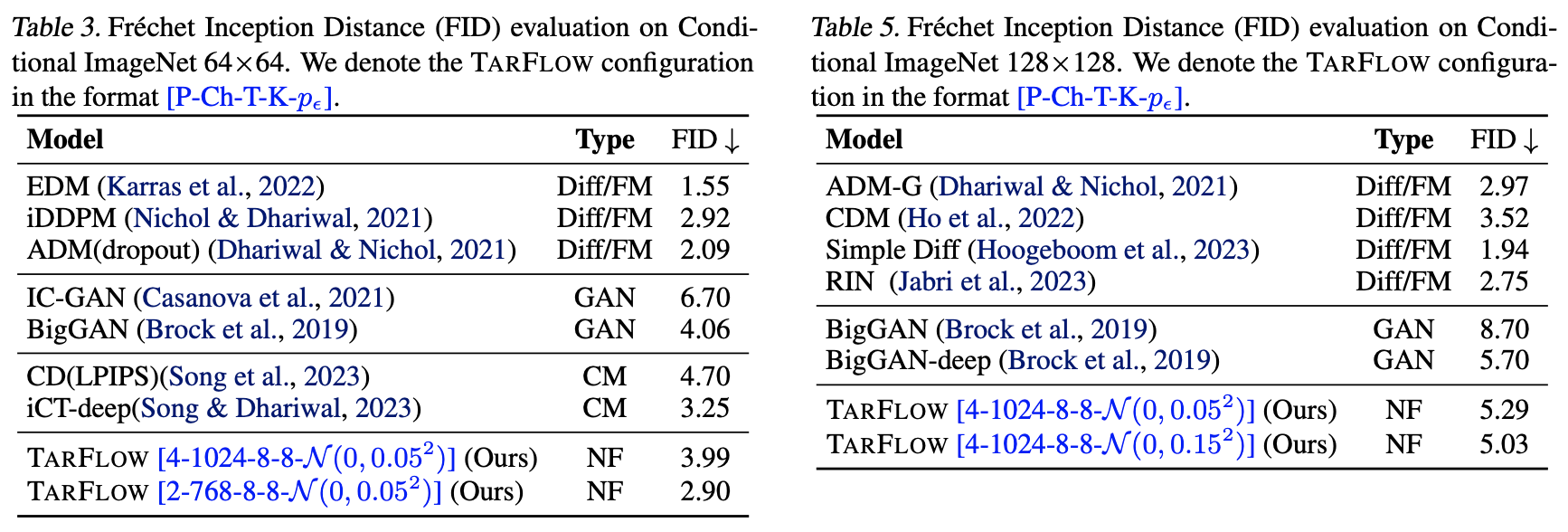

Glow only demonstrated relatively simple face generation, yet the artifacts were already quite apparent, not to mention more complex natural image generation. This shows that TARFLOW’s progress is more than just a small step. Quantitatively, its performance approaches the best of diffusion models and surpasses BigGAN, a SOTA representative of GANs:

It is worth noting that flow models are naturally one-step generation models and do not involve adversarial training like GANs; they are trained from start to finish with a single loss function. In some ways, their training is even simpler than that of diffusion models. Therefore, by bringing flow model performance up to par, TARFLOW simultaneously possesses the advantages of both GANs and diffusion models, while maintaining its own unique strengths (reversibility, ability to estimate log-likelihood, etc.).

Model Review

Returning to the main topic, let’s see what "magic pill" TARFLOW used to revitalize flow models. Before that, let’s briefly review the theoretical foundations of flow models. For a more detailed historical trace, refer to "Flowing with the Flow: NICE - Basic Concepts and Implementation" and "Flowing with the Flow: RealNVP and Glow - Heritage and Sublimation".

From the ultimate goal, both flow models and GANs hope to obtain a deterministic function \boldsymbol{x}=\boldsymbol{g}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{z}) that maps random noise \boldsymbol{z}\sim\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0},\boldsymbol{I}) to images \boldsymbol{x} of the target distribution. In the language of probability distributions, this means modeling the target distribution in the following form: \begin{equation} q_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}) = \int \delta(\boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{g}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{z}))q(\boldsymbol{z})d\boldsymbol{z}\label{eq:q-int} \end{equation} where q(\boldsymbol{z}) = \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0},\boldsymbol{I}) and \delta() is the Dirac delta function. The ideal goal of training a probabilistic model is maximum likelihood, using -\log q_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}) as the loss function. However, the current q_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}) contains an integral, which has only formal meaning and cannot be used for training.

At this point, flow models and GANs "part ways." GANs roughly use another model (the discriminator) to approximate -\log q_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}), leading to alternating training. Flow models, on the other hand, design an appropriate \boldsymbol{g}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{z}) so that the integral [eq:q-int] can be calculated directly. What conditions are needed to calculate the integral [eq:q-int]? Let \boldsymbol{y} = \boldsymbol{g}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{z}), with its inverse function being \boldsymbol{z} = \boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{y}). Then: \begin{equation} d\boldsymbol{z} = \left|\det \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{z}}{\partial \boldsymbol{y}}\right|d\boldsymbol{y} = \left|\det \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{y})}{\partial \boldsymbol{y}}\right|d\boldsymbol{y} \end{equation} and \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} q_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}) =&\, \int \delta(\boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{g}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{z}))q(\boldsymbol{z})d\boldsymbol{z} \\ =&\, \int \delta(\boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{y})q(\boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{y}))\left|\det \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{y})}{\partial \boldsymbol{y}}\right|d\boldsymbol{y} \\ =&\, q(\boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}))\left|\det \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x})}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}}\right| \end{aligned} \end{equation} Therefore: \begin{equation} -\log q_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}) = -\log q(\boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x})) - \log \left|\det \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x})}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}}\right| \end{equation} This indicates that calculating the integral [eq:q-int] requires two conditions: first, knowing the inverse function \boldsymbol{z} = \boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}) of \boldsymbol{x} = \boldsymbol{g}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{z}); second, needing to calculate the determinant of the Jacobian matrix \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x})}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}}.

Affine Coupling

To this end, flow models proposed a key design—the "Affine Coupling Layer": \begin{equation} \begin{aligned}&\boldsymbol{h}_1 = \boldsymbol{x}_1\\ &\boldsymbol{h}_2 = \exp(\boldsymbol{\gamma}(\boldsymbol{x}_1))\otimes\boldsymbol{x}_2 + \boldsymbol{\beta}(\boldsymbol{x}_1)\end{aligned}\label{eq:couple} \end{equation} where \boldsymbol{x} = [\boldsymbol{x}_1,\boldsymbol{x}_2], and \boldsymbol{\gamma}(\boldsymbol{x}_1), \boldsymbol{\beta}(\boldsymbol{x}_1) are models that take \boldsymbol{x}_1 as input and produce outputs with the same shape as \boldsymbol{x}_2, and \otimes denotes the Hadamard product. This equation says that \boldsymbol{x} is split into two parts (the split is arbitrary and does not require equal sizes), one part is output unchanged, and the other part is transformed according to specified rules. Note that the affine coupling layer is reversible, with its inverse being: \begin{equation} \begin{aligned}&\boldsymbol{x}_1 = \boldsymbol{h}_1\\ &\boldsymbol{x}_2 = \exp(-\boldsymbol{\gamma}(\boldsymbol{h}_1))\otimes(\boldsymbol{h}_2 - \boldsymbol{\beta}(\boldsymbol{h}_1))\end{aligned} \end{equation} This satisfies the first condition of reversibility. On the other hand, the Jacobian matrix of the affine coupling layer is a lower triangular matrix: \begin{equation} \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{h}}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}} = \begin{pmatrix}\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{h}_1}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}_1} & \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{h}_1}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}_2} \\ \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{h}_2}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}_1} & \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{h}_2}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}_2}\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}\boldsymbol{I} & \boldsymbol{O} \\ \frac{\partial (\exp(\boldsymbol{\gamma}(\boldsymbol{x}_1))\otimes\boldsymbol{x}_2 + \boldsymbol{\beta}(\boldsymbol{x}_1))}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}_1} & \text{diag}(\exp(\boldsymbol{\gamma}(\boldsymbol{x}_1)))\end{pmatrix} \end{equation} The determinant of a triangular matrix is the product of its diagonal elements, so: \begin{equation} \log\left|\det\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{h}}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}}\right| = \sum_i \boldsymbol{\gamma}_i(\boldsymbol{x}_1) \end{equation} That is, the log-absolute-determinant of the Jacobian matrix equals the sum of the components of \boldsymbol{\gamma}(\boldsymbol{x}_1), which satisfies the second condition of computability.

The affine coupling layer was first proposed in RealNVP. NVP stands for "Non-Volume Preserving," a name that contrasts with the special case where \boldsymbol{\gamma}(\boldsymbol{x}_1) is identically zero, known as the "Additive Coupling Layer" proposed in NICE. The characteristic of the additive coupling layer is that its Jacobian determinant equals 1, meaning it is "volume-preserving" (the geometric meaning of the determinant is volume).

Note that if multiple affine coupling layers are directly stacked, \boldsymbol{x}_1 will remain unchanged throughout, which is not what we want. We want to map the entire \boldsymbol{x} to a standard normal distribution. To solve this, before applying each affine coupling layer, we must "shuffle" the input components in some way so that no component remains unchanged. This "shuffling" operation corresponds to a permutation matrix transformation, whose absolute determinant is always 1.

Core Improvements

So far, these are the basic contents of flow models. Now we enter the specific contributions of TARFLOW.

First, TARFLOW notes that the affine coupling layer [eq:couple] can be generalized to multi-block partitioning, splitting \boldsymbol{x} into more parts [\boldsymbol{x}_1,\boldsymbol{x}_2,\cdots,\boldsymbol{x}_n], and then operating according to similar rules: \begin{equation} \begin{aligned}&\boldsymbol{h}_1 = \boldsymbol{x}_1\\ &\boldsymbol{h}_k = \exp(\boldsymbol{\gamma}_k(\boldsymbol{x}_{< k}))\otimes\boldsymbol{x}_k + \boldsymbol{\beta}_k(\boldsymbol{x}_{< k})\end{aligned}\label{eq:couple-2} \end{equation} where k > 1 and \boldsymbol{x}_{< k}=[\boldsymbol{x}_1,\boldsymbol{x}_2,\cdots,\boldsymbol{x}_{k-1}]. Its inverse operation is: \begin{equation} \begin{aligned}&\boldsymbol{x}_1 = \boldsymbol{h}_1\\ &\boldsymbol{x}_k = \exp(-\boldsymbol{\gamma}_k(\boldsymbol{x}_{< k}))\otimes(\boldsymbol{h}_k - \boldsymbol{\beta}_k(\boldsymbol{x}_{< k}))\end{aligned}\label{eq:couple-2-inv} \end{equation} Similarly, the log-absolute-determinant of the Jacobian for this generalized version is the sum of all components of \boldsymbol{\gamma}_2(\boldsymbol{x}_{< 2}),\cdots,\boldsymbol{\gamma}_n(\boldsymbol{x}_{< n}), satisfying both conditions. This generalized prototype was first proposed in IAF in 2016, even earlier than Glow.

Why did subsequent work rarely delve into this direction? This is largely due to historical reasons. In the early days, the main architecture for CV models was CNNs. Using CNNs requires features to satisfy local correlation, which led to partitioning \boldsymbol{x} only in the channel dimension. Because each layer requires a shuffling operation, if partitioning were chosen in the spatial dimensions (height and width), the features would lose local correlation after random shuffling, making CNNs unusable. Furthermore, partitioning into many parts in the channel dimension makes it difficult for multiple channel features to interact efficiently.

However, in the Transformer era, the situation is completely different. The input to a Transformer is essentially an unordered set of vectors; in other words, it does not rely on local correlation. Therefore, with Transformer as the main architecture, we can choose to partition in the spatial dimension, which is "Patchify." Additionally, the form \boldsymbol{h}_{k} = \cdots(\boldsymbol{x}_{< k}) in equation [eq:couple-2] means this is a Causal model, which can also be efficiently implemented with a Transformer.

Besides the formal fit, what is the essential benefit of partitioning in the spatial dimension? This goes back to the goal of flow models: \boldsymbol{g}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{z}) turns noise into images, and the inverse model \boldsymbol{f}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}) turns images into noise. Noise is characterized by randomness, while images are characterized by local correlation. Thus, one of the keys to turning images into noise is to break this local correlation. Directly using Patchify in the spatial dimension, combined with the shuffling operation inherent in coupling layers, is undoubtedly the most efficient choice.

Therefore, equation [eq:couple-2] and Transformer are a "perfect match." This is the meaning of the first three letters of TARFLOW (Transformer AutoRegressive Flow) and its core improvement.

Denoising

A common training trick for flow models is dequantization/noising, which involves adding a small amount of noise to images before feeding them into the model for training. Although we treat images as continuous vectors, they are actually stored in a discrete format. Adding noise can further smooth this discontinuity, making images closer to continuous vectors. The addition of noise also prevents the model from over-relying on specific details in the training data, thereby reducing the risk of overfitting.

Adding noise is a basic operation for flow models and was not first proposed by TARFLOW. What TARFLOW proposed is denoising. Theoretically, a flow model trained on noisy images will also produce noisy generation results. Previously, flow model generation quality wasn’t high enough for this noise to matter much. But as TARFLOW has pushed the capabilities of flow models higher, denoising has become imperative; otherwise, the noise becomes a major factor affecting quality.

How to denoise? Train another denoising model? There’s no need. As proved in "From Denoising Autoencoders to Generating Models", if q_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}) is the probability density function trained after adding noise \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0},\sigma^2 \boldsymbol{I}), then: \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{r}(\boldsymbol{x}) = \boldsymbol{x} + \sigma^2 \nabla_{\boldsymbol{x}} \log q_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}) \end{equation} is the theoretically optimal solution for the denoising model. So with q_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}), we don’t need to train a separate denoising model; we can denoise directly using the above formula. This is another advantage of flow models. Because of the denoising step, TARFLOW’s input noise was changed to a Gaussian distribution, and the noise variance was appropriately increased, which is one reason for its better performance.

In summary, the complete sampling process for TARFLOW is: \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{z}\sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0},\boldsymbol{I}) ,\quad \boldsymbol{y} =\boldsymbol{g}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{z}),\quad\boldsymbol{x} = \boldsymbol{y} + \sigma^2 \nabla_{\boldsymbol{y}} \log q_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{y}) \end{equation}

Further Reflections

At this point, the key changes in TARFLOW compared to previous flow models have been introduced. For other model details, readers can refer to the original paper or the official open-source code.

Below are some of the author’s thoughts on TARFLOW.

First, it should be noted that although TARFLOW achieves SOTA results, its sampling speed is actually not as fast as expected. The original paper’s appendix mentions that sampling 32 ImageNet64 images on an A100 takes about 2 minutes. Why is it so slow? Looking closely at the inverse of the coupling layer [eq:couple-2-inv], we find it is actually a non-linear RNN! Non-linear RNNs can only be calculated serially, which is the root cause of the slowness.

In other words, TARFLOW is actually a model that is fast to train but slow to sample. Of course, if we are willing, we could also make it slow to train and fast to sample; in short, one side of the forward and inverse passes will inevitably be slow. This is a disadvantage of multi-block affine coupling layers and a major direction for improvement if TARFLOW is to be further popularized.

Secondly, the term AR in TARFLOW easily brings to mind the currently mainstream autoregressive LLMs. Can the two be integrated for multimodal generation? Honestly, it’s difficult. The AR in TARFLOW is purely a requirement of the affine coupling layer, and there is shuffling before the coupling layer, so it is not a true Causal model but rather a thorough Bi-Directional model. Therefore, it does not integrate well with the AR of text.

Overall, if TARFLOW can further increase its sampling speed, it will be a very competitive pure vision generation model. Besides simple training and excellent results, the reversibility of flow models has another advantage: as mentioned in "The Reversible Residual Network: Backpropagation Without Storing Activations", backpropagation can be done without storing activation values, and the cost of recomputation is much lower than that of ordinary models.

As for whether it could become a unified architecture for multimodal LLMs, it can only be said that it is not yet clear.

Renaissance

Finally, let’s talk about the "Renaissance" of deep learning models.

In recent years, many works have attempted to combine current insights to reflect on and improve models that seemed outdated, yielding new results. Besides TARFLOW’s attempt to revitalize flow models, there is also "The GAN is dead; long live the GAN! A Modern GAN Baseline", which refines various combinations of GANs to achieve similarly competitive results.

Earlier, works like "Improved Residual Networks for Image and Video Recognition" and "Revisiting ResNets: Improved Training and Scaling Strategies" took ResNet to the next level, and "RepVGG: Making VGG-style ConvNets Great Again" brought back the classic VGG. Of course, SSMs and Linear Attention cannot go unmentioned; they represent the "Renaissance" of RNNs.

I look forward to this "Renaissance" trend becoming even more intense, as it allows us to gain a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of models.

Please include the original address when reprinting: https://kexue.fm/archives/10667

For more detailed reprinting matters, please refer to: Science Space FAQ