We know that in RoPE, the formula for calculating frequencies is \theta_i = b^{-2i/d}, where the default value for the base b is 10,000. Currently, a mainstream approach for Long Context is to first pre-train on b=10000 with short texts and then increase b for fine-tuning on long texts. The starting point for this is the NTK-RoPE introduced in "The Road to Transformer Upgrade: 10. RoPE is a \beta-ary Encoding". It inherently possesses good length extrapolation properties; using a larger b for fine-tuning results in a smaller initial loss and faster convergence compared to fine-tuning without modifications. This process gives the impression that increasing b is entirely due to the "short-then-long" training strategy. If one were to train on long texts from the beginning, would it still be necessary to increase b?

A paper from last week, "Base of RoPE Bounds Context Length", attempts to answer this question. It investigates the lower bound of b based on a desired property, pointing out that larger training lengths themselves necessitate a larger base, regardless of the training strategy. The entire analytical approach is quite enlightening. Let’s explore it together.

Desired Properties

We won’t introduce RoPE in detail here. It is essentially a block diagonal matrix: \begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n = \scriptsize{\left(\begin{array}{cc:cc:cc:cc} \cos n\theta_0 & -\sin n\theta_0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \sin n\theta_0 & \cos n\theta_0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \hdashline 0 & 0 & \cos n\theta_1 & -\sin n\theta_1 & \cdots & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \sin n\theta_1 & \cos n\theta_1 & \cdots & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \hdashline \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ \hdashline 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \cdots & \cos n\theta_{d/2-1} & -\sin n\theta_{d/2-1} \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \cdots & \sin n\theta_{d/2-1} & \cos n\theta_{d/2-1} \\ \end{array}\right)} \end{equation} It then utilizes the identity \begin{equation} (\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_m \boldsymbol{q})^{\top}(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n \boldsymbol{k}) = \boldsymbol{q}^{\top} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_m^{\top}\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_n \boldsymbol{k} = \boldsymbol{q}^{\top} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} \boldsymbol{k} \end{equation} to inject absolute position information into \boldsymbol{q} and \boldsymbol{k}, automatically achieving a relative position effect. Here \theta_i = b^{-2i/d}, and the value of b is the problem we are discussing.

In addition to injecting position information, we expect RoPE to possess two ideal properties for better performance: 1. Long-term decay, meaning tokens closer in position receive more attention on average; 2. Semantic aggregation, meaning semantically similar tokens receive more attention on average. We previously discussed the first point in "The Road to Transformer Upgrade: 2. Rotary Positional Encoding (RoPE)"; RoPE indeed exhibits a certain degree of long-term decay.

Next, we analyze the second point.

Inequality Relationship

Semantic aggregation means that when \boldsymbol{k} is close to \boldsymbol{q}, regardless of their relative distance n-m, their attention score \boldsymbol{q}^{\top} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} \boldsymbol{k} should be larger on average (at least larger than that of two random tokens). To obtain a quantitative conclusion, we further simplify the problem by assuming each component of \boldsymbol{q} is independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.), with a mean of \mu and a variance of \sigma^2.

Now we consider two different types of \boldsymbol{k}: one is \boldsymbol{q} plus a zero-mean perturbation

\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, denoted as

\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}} = \boldsymbol{q} +

\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, representing a token semantically

similar to \boldsymbol{q}; the other

assumes \boldsymbol{k} is i.i.d. with

\boldsymbol{q}, representing two random

tokens. According to the second ideal property, we hope to have: \begin{equation}

\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{q},\boldsymbol{k},\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}\big[\boldsymbol{q}^{\top}

\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} \tilde{\boldsymbol{k}} -

\boldsymbol{q}^{\top} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} \boldsymbol{k}\big]

\geq 0

\end{equation} Note that we repeatedly emphasized "on average,"

meaning we only expect an average trend rather than strict adherence at

every point, which is why we added the mathematical expectation \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{q},\boldsymbol{k},\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}.

Based on our assumptions and the definition of RoPE, we can calculate

the above expression specifically: \begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

&

\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{q},\boldsymbol{k},\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}\big[\boldsymbol{q}^{\top}

\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} (\boldsymbol{q} +

\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}) - \boldsymbol{q}^{\top}

\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} \boldsymbol{k}\big] \\[5pt]

=& \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{q}}\big[\boldsymbol{q}^{\top}

\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} \boldsymbol{q}\big] -

\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{q},\boldsymbol{k}}\big[\boldsymbol{q}^{\top}

\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} \boldsymbol{k}\big] \\[5pt]

=& \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{q}}\big[\boldsymbol{q}^{\top}

\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} \boldsymbol{q}\big] -

\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{q}}[\boldsymbol{q}]^{\top}\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m}

\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{k}}[\boldsymbol{k}] \\[5pt]

=& \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{q}}\big[\boldsymbol{q}^{\top}

\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} \boldsymbol{q}\big] -

\mu^2\boldsymbol{1}^{\top}\boldsymbol{\mathcal{R}}_{n-m} \boldsymbol{1}

\\[5pt]

=& \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{q}}\left[\sum_{i=0}^{d/2-1} (q_{2i}^2 +

q_{2i+1}^2)\cos (n-m)\theta_i\right] - \sum_{i=0}^{d/2-1} 2\mu^2\cos

(n-m)\theta_i \\[5pt]

=& \sum_{i=0}^{d/2-1} 2(\mu^2 + \sigma^2)\cos (n-m)\theta_i -

\sum_{i=0}^{d/2-1} 2\mu^2\cos (n-m)\theta_i \\[5pt]

=& \sum_{i=0}^{d/2-1} 2\sigma^2\cos (n-m)\theta_i \\

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} If the maximum training length is L, then n-m \leq

L-1. Therefore, the second ideal property can be approximately

described by the following inequality: \begin{equation}

\sum_{i=0}^{d/2-1} \cos m\theta_i \geq 0,\quad m\in\{0,1,2,\cdots,L-1\}

\label{neq:base}

\end{equation} Where L is the

maximum length, a hyperparameter chosen before training, and d is the model’s head_size.

According to the general settings of LLAMA, d=128. This means the only adjustable

parameter in the above equation is b in

\theta_i = b^{-2i/d}. In "The Road to Transformer Upgrade:

1. Tracing the Source of Sinusoidal Positional Encoding", we briefly

explored this function. Its overall trend is decaying; the larger b is, the slower the decay, and the larger

the corresponding continuous non-negative interval. Thus, there exists a

minimum b such that the above

inequality holds consistently: \begin{equation}

b^* =

\inf\left\{\,\,b\,\,\,\left|\,\,\,f_b(m)\triangleq\sum_{i=0}^{d/2-1}

\cos m b^{-2i/d} \geq 0,\,\, m\in\{0,1,2,\cdots,L-1\}\right.\right\}

\end{equation}

Numerical Solution

Since f_b(m) involves the summation of multiple trigonometric functions and \theta_i is non-linear with respect to i, it is hard to imagine an analytical solution to the above problem. Therefore, we must resort to numerical solutions. However, f_b(m) oscillates more frequently and irregularly as m increases, so even numerical solving is not straightforward.

Initially, I thought that if b_0 makes f_{b_0}(m) \geq 0 hold consistently, then f_b(m) \geq 0 would hold for all b \geq b_0, allowing for a binary search. However, this assumption is actually false, so the binary search failed. After thinking for a while without any optimization ideas, I consulted the authors of the original paper. They used an inverse function method: given b, finding the maximum L such that f_b(m) \geq 0 holds is relatively simple. Thus, one can obtain many (b, L) pairs. Theoretically, as long as enough b values are enumerated, the minimum b for any L can be found. However, there is a precision issue; the original paper calculated L up to 10^6, requiring b to be enumerated up to at least 10^8. If the enumeration interval is small, the computational cost is huge; if it is large, many solutions might be missed.

Finally, I decided to use "Jax + GPU" for a brute-force search to obtain higher precision results. The general process is:

1. Initialize b = 1000L (within 10^6, b = 1000L ensures f_b(m) \geq 0 holds);

2. Iterate k = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, performing the following:

) Divide [0, b] into 10^k equal parts, traverse the points, and check if f_b(m) \geq 0 holds;

) Take the smallest point where f_b(m) \geq 0 holds and update b;

3. Return the final b.

The final results are generally tighter than those in the original paper:

| L | 1k | 2k | 4k | 8k | 16k | 32k | 64k | 128k | 256k | 512k | 1M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b^* (Original) | 4.3e3 | 1.6e4 | 2.7e4 | 8.4e4 | 3.1e5 | 6.4e5 | 2.1e6 | 7.8e6 | 3.6e7 | 6.4e7 | 5.1e8 |

| b^* (This Post) | 4.3e3 | 2.7e4 | 8.4e4 | 2.1e6 |

Reference code:

from functools import partial

import numpy as np

import jax.numpy as jnp

import jax

@partial(jax.jit, static_argnums=(2,))

def f(m, b, d=128):

i = jnp.arange(d / 2)

return jnp.cos(m[:, None] * b ** (-2 * i[None] / d)).sum(axis=1)

@np.vectorize

def fmin(L, b):

return f(np.arange(L), b).min()

def bmin(L):

B = 1000 * L

for k in range(1, 6):

bs = np.linspace(0, 1, 10**k + 1)[1:] * B

ys = fmin(L, bs)

for b, y in zip(bs, ys):

if y >= 0:

B = b

break

return B

bmin(1024 * 128)Asymptotic Estimation

In addition to numerical solutions, we can also obtain an analytical estimation through asymptotic analysis. This estimation is smaller than the numerical results and is essentially the solution for d \to \infty, but it still leads to the conclusion that "b should increase as L increases."

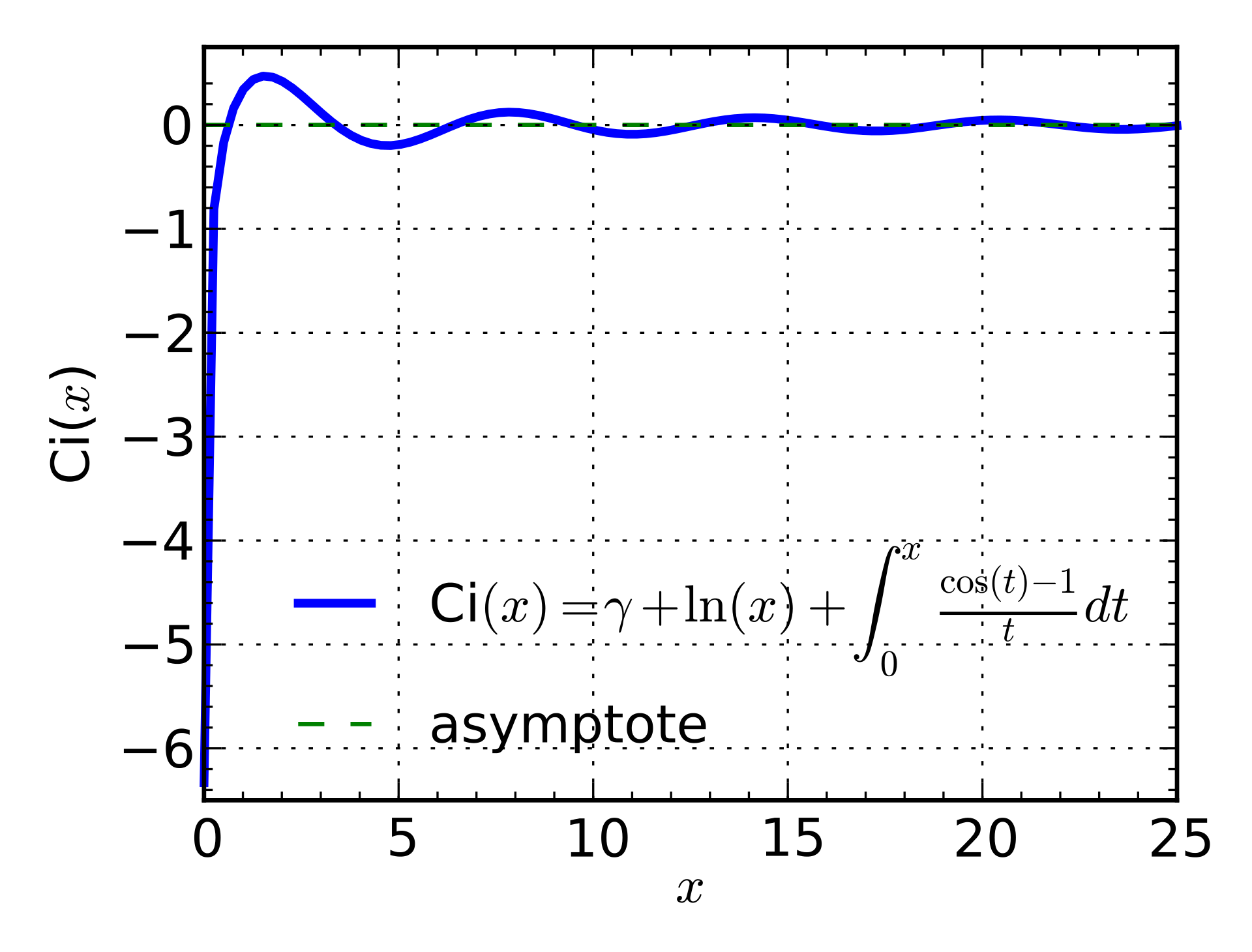

The idea for asymptotic estimation is to replace the summation with an integral: \begin{equation} f_b(m) = \sum_{i=0}^{d/2-1} \cos m b^{-2i/d} \approx \int_0^1 \cos m b^{-s} ds \xrightarrow{\text{let } t = mb^{-s}} \int_{mb^{-1}}^m \frac{\cos t}{t \ln b}dt \end{equation} We denote: \begin{equation} \text{Ci}(x) = -\int_x^{\infty} \frac{\cos t}{t} dt \end{equation} This is the previously studied Trigonometric integral. Using this notation, we can write: \begin{equation} f_b(m) \approx \frac{\text{Ci}(m) - \text{Ci}(mb^{-1})}{\ln b} \end{equation} The graph of \text{Ci}(x) looks like this:

Its first zero is x_0 = 0.6165\cdots. For m \geq 1, it can be seen that |\text{Ci}(m)| \leq 1/2, so \text{Ci}(m) is relatively a small term and can be ignored for asymptotic estimation. Then the problem approximately becomes \text{Ci}(mb^{-1}) \leq 0 holding for m = 1, 2, \cdots, L. We only need to ensure the corresponding mb^{-1} falls within the [0, x_0] interval, which means Lb^{-1} \leq x_0, i.e., \begin{equation} b \geq L / x_0 \approx 2L \end{equation} Or simply b^* = \mathcal{O}(L). Unsurprisingly, this result is smaller than the precise numerical result because it corresponds to d \to \infty. Superimposing an infinite number of trigonometric functions makes the function graph oscillate less and appear smoother (compared to finite d), resulting in a longer continuous non-negative interval for a fixed b, or conversely, a smaller b to keep f_b(m) non-negative for m = 0, 1, 2, \cdots, L-1 at a fixed L.

Partial Rotation

RoPE was proposed in 2021, initially only in a Chinese blog post. It later gained recognition and experimental validation from the EleutherAI organization before gradually spreading to the academic community. At that time, EleutherAI experiments found that applying RoPE to only a portion of the dimensions yielded slightly better results. Related content can be found here, here, and here. This operation was later used in their GPT-NeoX.

Of course, partial rotation is not yet the mainstream choice for current LLMs, but that doesn’t stop us from studying it. Perhaps it hasn’t become mainstream simply because we don’t understand it well enough. Why might partial rotation be superior? I found that the conclusions of this article can explain it to some extent. Taking the rotation of only half the dimensions as an example, it is mathematically equivalent to choosing the following \theta_i: \begin{equation} \theta_i = \left\{\begin{aligned}&b^{-4i/d},& i < d/4 \\ &0,&i \geq d/4\end{aligned}\right. \end{equation} In this case, we have: \begin{equation} \sum_{i=0}^{d/2-1} \cos m\theta_i = \sum_{i=0}^{d/4-1} (1+\cos mb^{-4i/d})\geq 0 \end{equation} That is, regardless of m and b, our desired inequality [neq:base] holds automatically. This means that from the perspective of this article, partial rotation provides position information while possessing better semantic aggregation capabilities, which may be more beneficial for model performance. At the same time, partial rotation might also be more beneficial for the model’s long-text capabilities because the inequality holds consistently; thus, according to this view, there is no need to modify b regardless of whether the training involves short or long texts.

It is worth mentioning that MLA proposed by DeepSeek also applies partial rotation. Although in the original derivation of MLA, partial rotation was more of a necessary compromise to integrate RoPE, combined with previous experimental results on partial rotation, perhaps part of MLA’s excellent performance can be attributed to partial rotation.

Summary

This article briefly introduced the paper "Base of RoPE Bounds Context Length". It discussed the lower bound of the RoPE base from the desired property of semantic aggregation, thereby pointing out that larger training lengths should choose a larger base. This is not merely a compromise to cooperate with the "short-then-long" training strategy and utilize NTK-RoPE to reduce initial loss, but a fundamental requirement.

For reprints, please include the original link: https://kexue.fm/archives/10122