In "Building from Scratch" Thoughts on Multimodality (Part 1): Lossless Input, we mentioned that the fundamental difficulty of image generation is the lack of a universal approximator for continuous probability densities. Of course, it’s not that they don’t exist at all; for instance, Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) can theoretically fit any probability density, and even GANs can essentially be understood as GMMs with an infinite number of mixed Gaussians. However, while GMMs have sufficient theoretical capacity, their maximum likelihood estimation is difficult, especially since they are generally not suitable for gradient-based optimizers, which limits their use cases.

Recently, a new paper from Google, "Fourier Basis Density Model", proposed a new solution for the one-dimensional case—using Fourier series for fitting. The analysis process in the paper is quite interesting, and the construction is very clever, making it well worth studying.

Problem Description

Some readers might question: what is the value of studying only the one-dimensional case? Indeed, if we only consider image generation scenarios, the value might be limited. However, one-dimensional probability density estimation has its own application value, such as in lossy data compression, so it remains a subject worth researching. Furthermore, even if we need to study multi-dimensional probability densities, we can transform them into multiple one-dimensional conditional probability density estimations via an autoregressive approach. Finally, the analysis and construction process itself is quite rewarding, so even practicing it as a mathematical analysis problem is highly beneficial.

Back to the topic. One-dimensional probability density estimation refers to estimating the probability density function of a sampling distribution given n real numbers x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n sampled from the same distribution. Methods for this problem can be divided into two categories: "non-parametric estimation" and "parametric estimation." Non-parametric estimation mainly refers to Kernel Density Estimation (KDE), which, like "Using Dirac Functions to Construct Smooth Approximations of Non-Smooth Functions", essentially uses Dirac functions for smooth approximation: \begin{equation} p(x) = \int p(y)\delta(x - y) dy = \mathbb{E}_{y\sim p(y)}[\delta(x - y)] \approx \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \delta(x - x_i) \label{eq:delta} \end{equation} However, \delta(x - y) is not a conventional smooth function, so we need to find a smooth approximation for it, such as \frac{e^{-(x-y)^2/2\sigma^2}}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}, which is the probability density function of a normal distribution. As \sigma \to 0, it becomes \delta(x-y). Substituting this into the above equation results in "Gaussian Kernel Density Estimation."

As we can see, kernel density estimation essentially memorizes the data; therefore, it can be inferred that its generalization ability is limited. Additionally, its complexity is proportional to the amount of data, making it impractical when the data scale is large. Thus, we need "parametric estimation," which involves constructing a family of probability density functions p_{\theta}(x) that are non-negative, normalized, and have a fixed number of parameters \theta. We can then solve for the parameters via maximum likelihood: \begin{equation} \theta^* = \mathop{\text{argmax}}_{\theta} \sum_{i=1}^n \log p_{\theta}(x_i) \end{equation} The key to this problem is how to construct a family of probability density functions p_{\theta}(x) with sufficient fitting capacity.

Existing Methods

The classic method for parametric probability density estimation is the Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM). Its starting point is also Equation [eq:delta] plus a Gaussian kernel, but instead of iterating through all data points as centers, it finds a finite number K of means and variances through training, constructing a model whose complexity is independent of the data volume: \begin{equation} p_{\theta}(x) = \frac{1}{K}\sum_{i=1}^K \frac{e^{-(x-\mu_i)^2/2\sigma_i^2}}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma_i}, \quad \theta = \{\mu_1, \sigma_1, \mu_2, \sigma_2, \dots, \mu_K, \sigma_K\} \end{equation} GMM is also commonly understood as a clustering method and is a generalization of K-Means, where \mu_1, \mu_2, \dots, \mu_K are cluster centers, and it adds variances \sigma_1, \sigma_2, \dots, \sigma_K. Due to the theoretical guarantees of Equation [eq:delta], GMM can theoretically fit any complex distribution when K is large enough and \sigma is small enough. Thus, GMM’s theoretical capacity is sufficient. However, the problem with GMM is that the form e^{-(x-\mu_i)^2/2\sigma_i^2} decays too quickly, leading to severe gradient vanishing. Consequently, it is usually solved using the EM algorithm (refer to "Matrix Capsules with EM Routing"), which is not easily optimized with gradient-based optimizers. This limits its application, and even with the EM algorithm, it usually only finds a sub-optimal solution.

The original paper also mentions a method called DFP (Deep Factorized Probability), specifically designed for one-dimensional probability density estimation, from the paper "Variational image compression with a scale hyperprior". DFP utilizes the monotonicity of the cumulative distribution function (CDF), i.e., the following integral: \begin{equation} \Phi(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x p(y)dy \in [0,1] \end{equation} must be monotonically increasing. If we can first construct a monotonically increasing function \Phi_{\theta}(x): \mathbb{R} \mapsto [0,1], then its derivative is a valid probability density function. How can we ensure that a model’s output increases monotonically with its input? DFP uses a multi-layer neural network to build the model and ensures: 1. All activation functions are monotonically increasing; 2. All multiplicative weights are non-negative. Under these two constraints, the model must exhibit monotonic increasing behavior. Finally, adding a Sigmoid function controls the range to [0,1].

The principle of DFP is simple and intuitive, but similar to flow-based models, such layer-by-layer constraints raise concerns about losing fitting capacity. Furthermore, since the model is entirely constructed from neural networks, according to previous conclusions like "Frequency Principle: Fourier Analysis Sheds Light on Deep Neural Networks", neural networks prioritize learning low-frequency signals during training. This might cause DFP to fit the peaks of the probability density poorly, resulting in over-smoothed fitting results. However, in many scenarios, the ability to fit peaks is one of the important indicators for measuring a probability modeling method.

Introducing Fourier

As the title "Fourier Basis Density Model" (hereafter referred to as FBDM) suggests, the new method proposed in the paper is based on fitting probability densities using Fourier series. To be fair, the idea of using Fourier series for fitting is not hard to come by; the difficulty lies in the fact that there is a critical non-negativity constraint that is not easy to construct. FBDM has successfully navigated these details, which is quite impressive.

For simplicity, we set the domain of x to [-1, 1]. Since any real number on \mathbb{R} can be compressed into [-1, 1] through transformations like \tanh, this setting does not lose generality. That is, the probability density function p(x) we are seeking is defined on [-1, 1], so we can write it as a Fourier series: \begin{equation} p(x) = \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} c_n e^{i\pi n x}, \quad c_n = \frac{1}{2}\int_{-1}^1 p(x) e^{-i\pi n x} dx \end{equation} However, what we are doing now is the reverse: we do not know p(x) to find its Fourier series; instead, we only know samples of p(x). We need to set p(x) in the following truncated Fourier series form and find the coefficients c_n through an optimizer: \begin{equation} f_{\theta}(x) = \sum_{n=-N}^{N} c_n e^{i\pi n x}, \quad \theta = \{c_{-N}, c_{-N+1}, \dots, c_{N-1}, c_N\} \label{eq:fourier-series} \end{equation} As is well known, for f_{\theta}(x) to be a valid probability density function, it must satisfy at least two conditions: \begin{equation} \text{Non-negativity: } f_{\theta}(x) \geq 0, \quad \text{Normalization: } \int_{-1}^1 f_{\theta}(x)dx = 1 \end{equation} The problem is that if c_n are arbitrary real or complex numbers, we cannot even guarantee that Equation [eq:fourier-series] is real-valued, let alone non-negative. Therefore, while using Fourier series for fitting is easy to think of, the difficulty lies in how to set the form of c_n such that the corresponding output is necessarily non-negative (as we will see later, under Fourier series, non-negativity is the hardest part; normalization is actually simple).

Ensuring Non-negativity

In this section, we look at the most difficult part of the paper: the construction of non-negativity. Of course, the difficulty here is not that the derivation is complex, but rather that it is very ingenious.

First, we know that a prerequisite for non-negativity is being real-valued, and ensuring a real value is relatively simple: \begin{equation} c_n^* = \left[\frac{1}{2}\int_{-1}^1 p(x) e^{-i\pi n x} dx\right]^* = \frac{1}{2}\int_{-1}^1 p(x) e^{i\pi n x} dx = c_{-n} \end{equation} It can be proven conversely that this condition is also sufficient. So, to ensure a real value, we only need to constrain c_n^* = c_{-n}. This is relatively easy to implement and also means that when the series in Equation [eq:fourier-series] acts as a probability density function, there are only N+1 independent parameters: c_0, c_1, \dots, c_N.

Regarding the non-negativity constraint, the original paper merely throws out a reference to "Herglotz’s theorem" and then directly provides the answer, with almost no derivation. I searched for Herglotz’s theorem and found few introductions, so I had to try to skip Herglotz’s theorem and understand the paper’s answer in my own way.

Consider any finite subset of integers \mathbb{K} \subseteq \mathbb{N} and any corresponding sequence of complex numbers \{u_k | k \in \mathbb{K}\}. We have: \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \sum_{n,m\in \mathbb{K}} u_n^* c_{n-m} u_m =&\, \sum_{n,m\in \mathbb{K}} u_n^* \left[\frac{1}{2}\int_{-1}^1 p(x) e^{-i\pi (n-m) x} dx\right] u_m \\ =&\, \frac{1}{2}\int_{-1}^1 p(x) \left[\sum_{n,m\in \mathbb{K}} u_n^* e^{-i\pi (n-m) x} u_m \right] dx \\ =&\, \frac{1}{2}\int_{-1}^1 p(x) \sum_{n,m\in \mathbb{K}} \left[(u_n e^{i\pi n x})^* (u_m e^{i\pi m x})\right] dx \\ =&\, \frac{1}{2}\int_{-1}^1 p(x) \left[\left(\sum_{n\in \mathbb{K}}u_n e^{i\pi n x}\right)^* \left(\sum_{m\in \mathbb{K}}u_m e^{i\pi m x}\right)\right] dx \\ =&\, \frac{1}{2}\int_{-1}^1 p(x) \left|\sum_{n\in \mathbb{K}}u_n e^{i\pi n x}\right|^2 dx \\ \geq&\, 0 \\ \end{aligned} \end{equation} The final \geq 0 depends on p(x) \geq 0, so we have derived a necessary condition for f_{\theta}(x) \geq 0: \sum_{n,m\in \mathbb{K}} u_n^* c_{n-m} u_m \geq 0. If we arrange all c_{n-m} into a large matrix (a Toeplitz matrix), then in linear algebra terms, this condition means that any submatrix formed by the intersection of rows and columns corresponding to \mathbb{K} is a positive semi-definite matrix in complex space. It can also be proven that this condition is sufficient; that is, an f_{\theta}(x) satisfying this condition is necessarily always greater than or equal to 0.

So the problem becomes how to find a complex sequence \{c_n\} such that the corresponding Toeplitz matrix \{c_{n-m}\} is positive semi-definite. This seems to make the problem more complex, but for readers familiar with time series, they might know a ready-made construction: the "autocorrelation coefficient." For any complex sequence \{a_k\}, the autocorrelation coefficient is defined as: \begin{equation} r_n = \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} a_k a_{k+n}^* \end{equation} It can be proven that r_{n-m} is necessarily positive semi-definite: \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \sum_{n,m\in \mathbb{K}} u_n^* r_{n-m} u_m =&\, \sum_{n,m\in \mathbb{K}} u_n^* \left(\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} a_k a_{k+n-m}^*\right) u_m \\ =&\, \sum_{n,m\in \mathbb{K}} u_n^* \left(\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} a_{k+m} a_{k+n}^*\right) u_m \\ =&\, \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\left(\sum_{n\in \mathbb{K}} a_{k+n} u_n\right)^*\left(\sum_{m\in \mathbb{K}} a_{k+m} u_m\right) \\ =&\, \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\left|\sum_{n\in \mathbb{K}} a_{k+n} u_n\right|^2 \\ \geq&\, 0 \end{aligned} \end{equation} Therefore, taking c_n in the form of r_n is a feasible solution. To ensure that the number of independent parameters for c_n is only N+1, we stipulate that a_k=0 when k < 0 or k > N. Then we get: \begin{equation} c_n = \sum_{k=0}^{N-n} a_k a_{k+n}^* \end{equation} This constructs the corresponding c_n such that the result of the Fourier series in Equation [eq:fourier-series] is necessarily non-negative, satisfying the non-negativity requirement of the probability density function.

General Results

At this point, the most difficult part of the problem—"non-negativity"—has been solved. The remaining normalization is simple because: \begin{equation} \int_{-1}^1 f_{\theta}(x)dx = \int_{-1}^1 \sum_{n=-N}^{N} c_n e^{i\pi n x} dx = 2c_0 \end{equation} So the normalization factor is 2c_0! Thus, we only need to set p_{\theta}(x) as: \begin{equation} p_{\theta}(x) = \frac{f_{\theta}(x)}{2c_0} = \frac{1}{2} + \sum_{n=1}^{N} \frac{c_n e^{i\pi n x} + c_{-n}e^{-i\pi n x}}{2c_0} = \text{Re}\left[\frac{1}{2} + \sum_{n=1}^N \frac{c_n}{c_0} e^{i\pi n x}\right], \end{equation} where c_n = \sum_{k=0}^{N-n} a_k a_{k+n}^* and \theta = \{a_0, a_1, \dots, a_N\}. This is a valid candidate for a probability density function.

Of course, this distribution is currently only defined on [-1, 1]. We need to extend it to the entire \mathbb{R}. This is not difficult; we first think of a transformation that compresses \mathbb{R} into [-1, 1] and then find the form of the probability density after the transformation. To do this, we can first estimate the mean \mu and variance \sigma^2 from the original samples, then use x = \frac{y-\mu}{\sigma} to transform it into a distribution with mean 0 and variance 1. Next, we can compress it into [-1, 1] via x = \tanh\left(\frac{y-\mu}{\sigma}\right). The corresponding new probability density function is: \begin{equation} q_{\theta}(y) = p_{\theta}(x)\frac{dx}{dy} = \frac{1}{\sigma}\text{sech}^2\left(\frac{y-\mu}{\sigma}\right) p_{\theta}\left(\tanh\left(\frac{y-\mu}{\sigma}\right)\right) \end{equation} From an end-to-end learning perspective, we can directly substitute the original data into the log-likelihood of q_{\theta}(y) for optimization (rather than compressing first and then optimizing), and we can even treat \mu, \sigma as trainable parameters to be adjusted together.

Finally, to prevent overfitting, we also need a regularization term. The purpose of regularization is to hope that the fitted distribution is slightly smoother and does not fall too much into local details. To this end, we consider the squared norm of the derivative of f_{\theta}(x) as the regularization term: \begin{equation} \gamma\int_{-1}^1 \left|\frac{df_{\theta}(x)}{dx}\right|^2 dx = \gamma\sum_{n=-N}^N 2\pi^2 n^2 |c_n|^2 \end{equation} From the final form, it can be seen that it increases the penalty weight for high-frequency coefficients, which helps the model avoid overfitting high-frequency details and improves generalization.

Extended Thinking

By now, we have completed all the theoretical derivations for FBDM. The rest is naturally to conduct experiments; we won’t repeat that part here and will directly look at the results from the original paper. Note that all coefficients and operations in FBDM are in the complex domain. Forcing them to be real would make the resulting forms much more complex, so for simplicity, they should be implemented directly based on the complex operations of the framework used (the original paper used Jax).

Before looking at the experimental results, let’s think about the evaluation metrics. In simulation experiments, we usually know the probability density expression of the true distribution, so the most direct metric is calculating the KL divergence or W-distance between the true and fitted distributions. Besides that, for probability density fitting, we are usually more concerned with the "peak" fitting effect. Assuming the probability density is smooth, it may have multiple local maxima; these local maxima are what we call peaks, or "modes." In many scenarios, the ability to accurately find more modes is more important than the overall distribution metric. For example, the basic idea of lossy compression is to keep only these modes to describe the distribution.

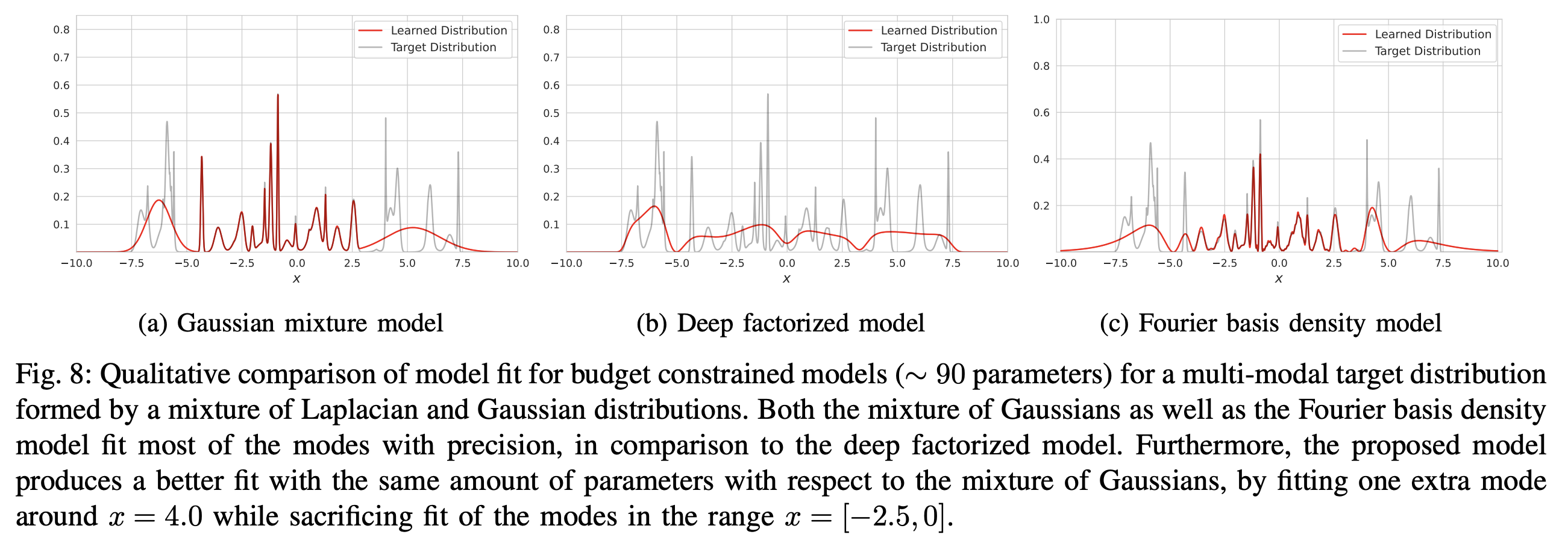

From the experimental results in the original paper, it can be seen that with the same number of parameters, FBDM performs better in terms of KL divergence and modes:

The reason for this advantage, I suspect, is that FBDM’s imaginary exponential form is essentially trigonometric functions. Unlike the negative exponentials in GMM, it doesn’t suffer from severe gradient vanishing. Therefore, gradient-based optimizers have a higher probability of finding a better solution. From this perspective, FBDM can also be understood as a "Softmax" for continuous probability densities, both using \exp as a basis to construct a probability distribution, except one uses real exponents and the other uses imaginary ones.

Compared to GMM, FBDM naturally has some disadvantages, such as being less intuitive, harder to sample from, and difficult to generalize to high dimensions (though DFP also shares these drawbacks). GMM is very intuitive, being a weighted average of a finite number of normal distributions. Sampling can be achieved through hierarchical sampling (first sampling the category, then the normal distribution). In contrast, FBDM does not have such an intuitive scheme and seems to require sampling via the inverse cumulative distribution function. That is, first find the CDF: \begin{equation} \Phi(x) = P(\leq x) = \int_{-1}^x p_{\theta}(t)dt = \frac{x+1}{2} + \text{Re}\left[\sum_{n=1}^{N} \frac{c_n}{c_0} \frac{e^{i\pi n x} - (-1)^n}{2i\pi n}\right] \end{equation} Then y = \Phi^{-1}(\varepsilon), \varepsilon \sim U[0,1] can achieve sampling. As for high-dimensional generalization, normal distributions inherently have high-dimensional forms, so generalizing GMM to any dimension is easy. However, if FBDM is directly generalized to D dimensions, there would be (N+1)^D parameters, which is clearly too complex. Alternatively, like Decoder-Only LLMs, one could use an autoregressive approach to transform it into multiple one-dimensional conditional probability density estimations. In short, it’s not that there are no ways, but they involve more twists and turns.

Conclusion

This article introduced a new idea for modeling one-dimensional probability density functions using Fourier series. The key lies in the ingenious construction of coefficients to constrain the Fourier series, whose range is originally in the complex domain, to become a non-negative function. The entire process is quite elegant and well worth learning.

Reprinting please include the original address: https://kexue.fm/archives/10007

For more detailed reprinting matters, please refer to: "Scientific Space FAQ"